Our Daily Bread 625: Various ‘Athos: Echoes From The Holy Mountain’

September 13, 2024

ALBUM FEATURE

DOMINIC VALVONA

Various ‘Athos: Echoes From The Holy Mountain’

(FLEE) 27th September 2024

“Let this place be your inheritance and your garden, a paradise and a haven of salvation for those seeking to be saved.”

And thus spoke, in Christian lore, the mysterious voice to the Blessed Virgin Mary as she set foot upon the lands around the Holy Mountain of Athos in Northeastern Greece, two millennia ago. Athonite (the Orthodox religious form that takes its name from Athanasios, a Byzantine monk who is considered the founder of the monastic community on the peninsula of Mount Athos) tradition tells of the exalted Mary’s planned journey from Jaffa to visit Lazarus in Cyprus. Fated to be blown off course, Mary and her party, which included St. John The Evangelist no less, were forced to anchor at the port of Klement, close to the present monastery of Iviron – one of twenty such monasteries to be built upon that sacred mountain and outlier of the course of centuries. But this was Pagan territory in those near ancient times, yet to be Christianised. The Virgin Mary however so fell in love with its idyllic beautified landscape and awe inspiring heights that she’s said to have blessed it. Mary’s famous Son then anointed it as her garden.

And so begins the Christian legend of Mount Athos, its long checkered – often beset by occupying enemies and theological conflicts – history and embrace of the Orthodox faith. Or at least that’s just one thread: one such origin story of many.

If we go back much further, and if Greek mythology is to be believed, this outcrop was named after the Gigante who, during this incredibly strong and aggressive race’s epic battle with the Gods of Olympus, tussled with Poseidon. Despite the name these warring offspring of Gaia were not actually giants, nor to be confused with the Titans. But somehow Athos was able to lope a humongous rock at the Sea God, which missed and fall into the Aegean, where it stands to this day. Other versions of this same origin myth say that Poseidon buried his adversary beneath it.

Mentioned in Homer’s Iliad, the histories of both Herodotus and Strabo, ancient references to Athos all remark upon its geography, strategic positioning – used as a route for Xerxes I and his invasion of the Greek kingdoms – and more fateful reputation to lure ships onto its rocks – during another invasion, this time on the city state of Thrace, the Persian commander Mardonius lost 300 ships and 20,000 men off that treacherous coastline. Pliny the Elder, who could always tell a good fib, wrote that the inhabitants of this pre-Christian landscape feasted upon the skins of vipers, the properties of which allowed them to live until 400 years of age. After the death of Alexander The Great, the architect Dinocrates is said to have proposed carving a statue of the Macedonian out of the mountain.

Historical records, documentation is slim on the matter, but the more modern history of Athos and its conversion to Christianity begins during the 4th century, and Constantine I’s reign (324 – 337 AD). It is recorded that followers of the faith were already established or living there however. But just a generation later, under the rule of Julian, its burgeoning churches were destroyed, its people forced to flee into the woods and more inaccessible areas. Believers must have lived and shared with pre-Christian Greeks and religions, as under Theodosius I’s reign in the later years of that same century, there were still traditional Greek temples standing – we know this, because they were unceremoniously destroyed during this period.

By the later period of the 7th century, Christian worship was in full flow, with Athos becoming a sanctuary to those escaping Islamic conquest. Many of the monks from the outlier desert regions of Egypt, sought protection abroad in Athos.

We emerge during the Byzantine era with old Rome all but destroyed, its empire now either overrun by various tribes/confederations/enemies, and its power either erased or enervated. The baton was picked up however, and a new Rome, of a kind, was built in Constantinople; long part of the original Roman empire, shared and split at various times amongst generals and rulers vying for control of the whole. One iconic character of this new epoch, the revered hermit and monk Euthymius The Younger, settled in Athos, followed by the already mentioned Athanasios the Athonite. The latter would famously build the large central church of the Protaton in the largest of the Athos settlements, Karyer – home to the famed “Axion Estin” icon of the Blessed Virgin Mary, and also the name of a hymn sung in divine services.

I’m in gratitude to Norman Davis and his impressive tome Europe: A History, for a concise outline of Athos. Davis tells us that the 9th century Byzantine Emperor Basil I formerly recognized the “Holy Mountain of Athos” as a territory reserved for monks and hermits in 885 AD. You may have noticed the absence of a sizable proportion of the populace from that, for women were banned from the “Garden of the Virgin” – there’s gratitude for you. Davis also writes that the first permanent monastery, the Great Laura, was founded in 936 AD.

The history just keeps on rolling; the rise and fall, the declines in waves over the next thousand years.

The centre of Orthodox theology to a degree, despite continued attempts of Catholic conversion in the next millennium and obvious intrigues of the Popes, the fortunes of Athos depended much on the outside support of strongmen, kings and emperors alike. As the Byzantine Empire, not before thwarting an invasion of this sanctified retreat, faded and the Ottoman rose, the Orthodox sect looked to new benefactors: interestingly enough, this included the sultans. A far too convoluted story follows, but it was the Serbian kings who offered that vital support and protection for a time. However, the Russians targeted this seat of international learning, swelling the monastic community with 5000 monks sent by St. Petersburg. Influence wise, Russia lasted until the revolution, by which time fortunes once more had changed as Europe suffered the devastations of World War I and the first of the Balkan Wars – Athos couldn’t help but suffer as a backdrop to all these events.

Decades of decay would follow until the 1980s saw another rise in numbers of monks. But Athos disappears into mysticism; a timeless part of Earth unbound to time.

Context is vital: history essential. For the publishing house/record label/curatorial/ethnologist platform FLEE has spent a year unraveling, digging and excavating and researching their grand project dedicated to the Athos monastic community. Regular readers will perhaps recognise the name and my review of the hub’s Ulyap Songs: Beyond Circassian Tradition purview. Echoes From The Holy Mountain is no less extensive and documented; arriving with an accompanying book of essays, articles, photos and commissioned artwork by a both Greek and international cast of experts and artists.

My opening history is but brief, but within the pages that accompany these both original recordings of Athos voices and visionary reworks and soundboards by contemporary experimental artists, you’ll find a fascinating story.

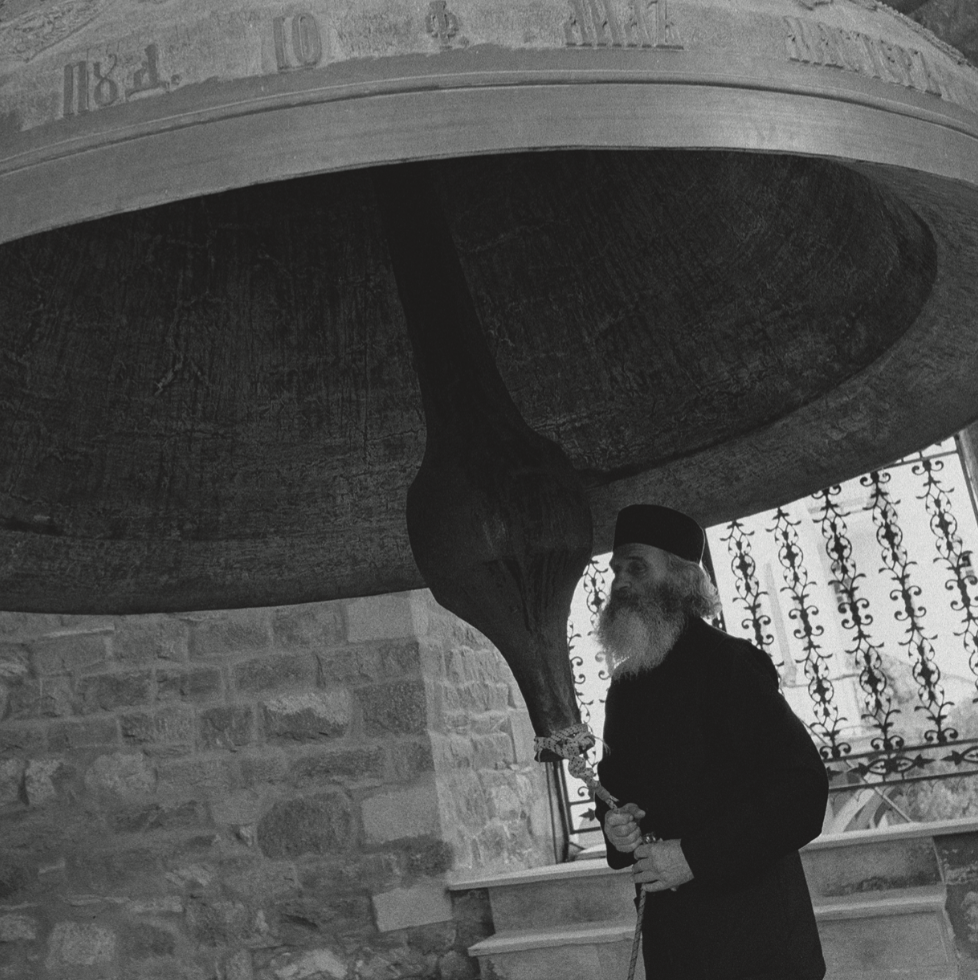

No one quite puts in the work that FLEE and their collaborators do, with the scope and range of academia wide and deep. Musically, across a double album vinyl format there’s a split between those artists, DJs and producers that have conjured up new peregrinations influenced by the source material, and a clutch of recordings taken in the 1960s and in recent times of the Daniilaioi Brotherhood Choir, Father Lazaros of the Grigoriou monastery, Father Germanos of the Vatopedi and Father Antypas – there’s also attributed performances to the Iviron and Simonopetra monasteries too.

The liturgy, holy communal a cappella voiced and near uninterrupted hummed, assonant harmonies of the monastic choirs stretch back to the Byzantine epoch; a mysterious, gilded age in which the Orthodox strand of Christianity flourished. You can easily picture such gold leafed mosaic scenes, as the incense burned in somber reverence to the Virgin Mary, the idol of Athos.

The only accompaniment to these beatific choral undulations and ascendant exaltations is the semantron percussive apparatus. Used to summon the monasteries to prayer at the start of a procession, strips of metal that hang from a wooden frame (although there are variations to the construction) are struck with a mallet. It sounds almost like a mix of thwacked leather and wooden poles being rhythmically shuttered. Opening both the original non-augmented recordings and used not only in the title but as the prompt for the first of the modern treatments, adaptations, the semantron ushers in the Vatopedi vespers, the evening prayer, and is veiled beneath a echo-y vapourous mist on the breathed, clock-chimed, fourth world jazz suffused Prins & Inre Kretson Group transformation.

Picking up on the near mystical, the atmospheric sanctuaries and timeless settings, each prayer, divine service, stanza travels beyond Athos; the soundings, language seem to reach out and draw comparisons to much of Eastern Europe, Russia, the Caucuses, and even India. Unmistakable is the Orthodox cannon, the rites. But I’m hearing parallels to other cultures, forms too, whether intentional, or for obvious reasons, because the reach is wide and overlaps former empires, conversions and borders. And so these recordings are ripe for further geographical transference, none more so than with Baba Zula legend Murat Ertel and his foil and wife Esma’s pastoral Mediterranean caravan ‘Garden Of Kibele’. The duo seems to reimagine a Japanese ceremonial garden transplanted to Byzantium Constantinople – cue courtly Medieval Velvet Underground echoes, a whistled flute, a detuned drum, a Jah Wobble bass, and obscured singing voices. It sounds like an Anatolian version of Hackedepicciotto.

Glorifying God to a fusion of the Orthodox, Turkey, the Hellenic, Med coastlines and Middle Eastern fuzzed-up grooves, the Athenian-born, but London-based, drummer and multi-instrumentalist Daniel Paleodimos evokes Mustafa Ozkent, Altin Gün and the Şatellites on the afflatus paean ‘Doxology’. Jimi Tenor cooks up a suitable inter-dimensional, near supernatural, soundtrack from haunted gramophone-like recordings on his tremulant, fluted and gravitas swelled ‘Idan Kuoromiehet’, and Jay Glass Dubs goes down the Daniel Lanois, Dennis Bovell and Finis Africae routes on the signature dubby, paddled and breathless “huh” reverberation ‘Synaptic Riddles’.

The German and American “improvised and spontaneous storytelling” pairing of Hilary Jeffery and Eleni Poulou cast a hallucinogenic spell of uneasy confessional sexual and dreamy obsession on the vaporous wisped ‘I Swim In Your Dreams’. Swaddled blows of sax can be heard in a cosmic air of post-punk dance and trip-hop – I’m thinking Deux Filles and Saáda Bonaire meeting Meatraffle in the cloisters.

Some repurposed, reimagined traverses seem to erase any trace of the monastic brethren’s intonations and hymnal divine stylings, whilst others feature the source material: albeit in an illusionary manner, or as a jump-off point for further mystification and flights of fantasy. As an overall package however, Echoes From The Holy Mountain is a deep survey of a near closed-off world and all the various attached liturgical and historical threads. FLEE reawaken an age-old practice, bringing to life traditions that, although interrupted and near climatically hindered, stretch back a millennium or more. No dusted ethnographical academic study for students but an impressive and important purview of reverential dedication and a lifetime of service, this project offers new perspectives and takes on the afflatus. Yet again the platform’s extensive research has brought together an international cast, with the main motivation being to work with tradition to create something respectful but freshly inviting and inquisitive. The historical sound, seldom witnessed or heard by outsiders, is reinvigorated, as a story is told through sonic exploration.