ALBUM PIECE/SAMUELE CONFICONI

In a synergy between our two great houses, each month the Monolith Cocktail shares a post (and vice versa) from our Italian pen pals at Kalporz. This month, a purview of the new Big Thief album, Dragon New Warm Mountain I Believe In You by Samuele Conficoni.

Big Thief ‘Dragon New Warm Mountain I Believe In You’ (4AD)

In the throes of a creative fire that has accompanied them for years and which is embodied notably in that of their leader, Adrianne Lenker, epicenter of the extraordinary harmony that the band has achieved since its excellent sophomore album, Capacity , a whirlwind of talent that has given life to the great UFOF and Two Hands and to the equally exceptional songs / instrumental , the solo album that Lenker released in the autumn of 2020, Big Thief proceeded to new lands by not limiting their range of action in any way and making treasure of the experiences accumulated so far. Dragon New Warm Mountain I Believe in You, their fifth album in six years, is the one that Lenker and associates, guitarist Buck Meek, bassist Max Oleartchik and drummer James Krivchenia – here for the first time also as a producer – are now and that shortly they may no longer be, ready for yet another unpredictable and authentic leap forward. The twenty songs on the album are yet another precious piece in the unstoppable and crackling growth path of one of the fittest and most inspired bands of recent years.

Elusive and changeable by nature, the American quartet has long been one with its own music. In fact, it is both what its members “hide” inside, a blanket of fog that somehow brings out the artistic act and makes those who produce it almost disappear, and what gives consistency to the very existences of four, because there is no note or sound that is not the result of their amazing understanding, a sort of competitive trance – to use a metaphor borrowed from the world of sport – which sees the Big Thief making the songs they create and perform. This is why it is in the music itself that they show themselves and that they are blurred, without there being any contradiction in this. In this sense Dragon, in its eighty minutes, it is a daring and decidedly won bet in the course of which the Big Thiefs explore dimensions that they had never explored yet, despite having traveled and described so many, and so different from each other, previously.

It is precisely the brotherhood between the four members of the group and their so clear-cut community of ideas and vision of things that makes everything that the Big Thief bring to life together spiritual and earthly. Here the branches of the cosmic and spiritual element of UFOF and the earthly and terrestrial element of Two Hands intertwine for the first time, condensed seamlessly, and if Dragon lacks conciseness and synthesis – lato sensu – which characterised its two illustrious predecessors is only because its strength lies precisely in its splendidly chaotic organisation, perhaps the best oxymoron that could describe the album, a sort of very personal White Album within the artistic path of the group. That “dragon in the new warm mountain” named in the text of the wonderful “anything” present on Lenker’s songs album now becomes the mysterious and pulsating presence around which this exceptional musical path takes shape and grows.

Driven by the need to give vent to a creative fire that for some years seems to really have no limits and by the need to base this on a sense of artistic freedom that is in no case negotiable, the four sew solid folk episodes on and for themselves, country rides, revealing ballads, psychedelic pop, electric rock blasts, smoky trip-hop hangover and amazing electronic hikes with nothing out of place. It is precisely this poikilía that holds the whole project together with a disconcerting clarity, and it is the allusive art that the band puts on its feet, with elegant and subtle quotes to John Prine and even Portishead, to name only two names, that weaves the fil rougevery fragile yet foundational that runs through the work, fundamental in the understanding of this magnum opus , magnum both in depth and in length. It is for this reason that episodes such as “Flower of Blood”, sharp and irrepressible, whose obstinate rhythm and whose wall of sound are almost unique in the production of the group, which goes in an electronic and distorted direction at other times, can sprout. of the record, the pertinacious “Heavy Bend” and the suffocating “Blurred View”. Even more difficult to describe is that hurricane of Proustian and Joycian images that is “Little Things” , sublime almost psychedelic pop rock that arises from an immersive and all-encompassing amalgam of vocals, guitars, bass and drums.

Dragon is obviously an extraordinary open window on Lenker’s songwriting qualities, in fact for several years she has already become one of the most popular composers in the American music scene. His about her sbragís about her and her own conception of writing emerge almost everywhere in the course of the unfolding of Dragon. A constant in Lenker’s writing, for example, is to try to approach something potentially human that perhaps, however, is not human, and to do it as if one were alien to (and alienated from) it. “Simulation Swarm” is the most perfect realisation of this design: the discomfort in perceiving one’s own corporeality or in not being able to harmonize it with that of others makes one instant weak and suddenly invincible in the immediately following instant; you are on the verge of giving in and letting yourself be overcome by the tumultuous chaos of life until a moment later you are ready to fight even with your bare hands to survive and try to make contact with the creature you are approaching. It is a feeling that can be read in some passages of the Memorial by Paolo Volponi or in some poems-fragments by Giuseppe Ungaretti. Lenker always manages to find a point of balance before the fracture becomes irremediable: the magic of his songs lies above all in this.

The themes that the songs touch are many and fundamental. Lenker’s writing, as we know by now, somehow envelops any nuance of the world, of the existing and the non-existent. In “Certainty”, the only song on the record that, in addition to Lenker’s signature, also carries Meek’s, the pure linguistic game and the desire to concretely represent something that cannot be touched by hand interpenetrate: “Maybe I love you is a river so high / Maybe I love you is a river so low ”, Lenker sings, words that in their apparent simplicity betray an allegorical meaning that is impossible to exhaust in a few verses. Thus, we remain clinging to the passing epiphanies that the piece, through its solid gait built around a captivating melody, disseminates like crumbs of bread in a very dense and dark forest. “Sit on the phone, watch TV / Romance, action, mystery”: it is as if, as Lenker lists them, those actions and names suddenly materialise in front of us, and also the things that once seemed to us more natural and banal now they are part of a primeval and sincere cosmos and therefore take on an inestimable value. And also in “Spud Infinity” the horror vacui of the situations that the song paints us in front of our eyes becomes a statement of solid and highly original poetics, a true instruction manual on how to strike in the depths of the soul through irony and fantasy.

Another element that makes Dragon in part different from its predecessors is the strong collaborative aspect that characterises it. In reality, the external musicians involved are not numerous, but it is the band’s sound that is even wider and more multicoloured than the already very deep and composite one of the twin albums released in 2019. Those represented the akmè of two complementary world-views, and the focus rigorous and centered that they pursued is inevitably and rightly avoided here, shunned from the beginning, in the very conception of what has become Dragon. To make the disc’s nuances even more diversified and iridescent is, for example, the rural fiddle that goes wild in the joyful “Spud Infinity”, whose marked irony actually hides deep and disturbing reflections between the lines, as usual, as revealed by the same Lenker in a recent interview with Pitchfork , and in the romantic “Red Moon”, with a bubbly rhythm. There are also dazzling and bewitching purely folk moments during which Lenker is alone with her voice and guitar, as happens in the enchanting “The Only Place”, one of the most breathtaking moments of the record. “The only place that matters / Is by your side”, Lenker sings as a flame consumes her, as if carried away by her own song.

The mischievously messy appearance that Dragon seems to have betrays an extremely careful and precise organisation. The determination of the group is impressive and James Krivchenia’s production is versatile and detailed and is emblematic of the group’s choice to record the album in four different locations, Massachusetts, New York, California and Arizona, which in part follows what had happened. for UFOF and Two Hands , the first, dreamlike and ecstatic, recorded in the Seattle metropolitan area, the second, pungent and direct, recorded between California and Arizona. In Dragon coexist an even greater number of places and people encountered in this musical and geographical journey. To connect the dots is the Lenker’s excellent songwriting is his voice, warm and enveloping, and that kind of spell that seems to kidnap the quartet every time he starts playing, a quartet that, owned by some daimon , is ready once again to amaze us.

RATED:: 80/100

(Samuele Conficoni)

The Kalporz Album Awards 2021

December 17, 2021

Monolith Cocktail X Kalporz/Words: Editorial Team

The last piece of synergy between the Monolith Cocktail and our partners at Kalporz in 2021 relays the Italian site’s recent top twenty placed albums of the year feature. Look out for future collaborations in 2022.

We can discuss the musical quality of a year, but there is little to say about the quantity of 2021: all the artists who had perhaps hesitated to release their works in 2020, due to clashes with the novelty of the pandemic that made it evident that it would not have been possible to go on tour, they published what they had to, understanding that – unfortunately – the ‘newnormal’ was not only the motto of the Primavera Sound a few years ago but also the slogan of a new normal made up of fragmented, contingent, postponed live dates , made for the broken cap while escaping the next looming wave. So we found ourselves faced with a gargantuan production, which, is the law of large numbers, for some albums has also materialised into truly beautiful works.

As always since the streaming era has existed there cannot be a single star, but this time there was an award-winning album: the artist who made almost everyone agree was Little Simz , first for Popmatters , Albumism , BBC Radio 6 Music , NBHAP , Exclaim! , Dutch OOR , The Skinny and second for NME . And if according to “social sensations” Black Country should have depopulated , New Road , in reality only first for Loud And Quiet even if present in more than one list in places of honour, a disc not as simple as that of Floating Points, Pharoah Sanders & The London Symphony Orchestra instead “won” for Mojo , Paste Magazine , TIME and The Vinyl Factory , while less generalised choices were those of Pitchfork ( Jazmine Sullivan , shared by Entertainment Weekly and NPR Music ), of Consequence of Sound ( Tyler, the Creator ) and Crack Magazine ( John Glacier ).

All these discs, however (ALERT SPOILER), are also contained in our list, while choices that you will not find here on Kalporz are those of The Quietus The Bug (to which we have dedicated the cover of September), of Uncut with The Weather Station , Far Out Magazine with Dry Cleaning and NME which instead awarded Sam Fender .

And for us at Kalporz? We let you “shake” below, telling you that for the second time in our more than twenty years of life a band wins after having already won the Kalporz Awards in the past: it had already happened for Radiohead, reached this year by a special band.

But we have already talked too much: off to the rankings.

20. DAMON ALBARN, “The Nearer The Mountain, More Pure The Stream Flows”

Maybe we should all do like Albarn, especially in these times: go to Iceland and look at the snow and volcanoes from a window in our house. But we are here, and at least we can listen to this second solo album of his that got inspired in that intimate way with nature.

19. FLOATING POINTS, PHAROAH SANDERS & THE LONDON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, “Promises”

The electronic jazz path of Floating Points has been going on for years now, managing to churn out interesting results such as the excellent debut Aelenia in 2015. On this release he manages to collaborate with a music giant like Pharoah Sanders, and without distorting himself they give an LP which will probably continue to play in our systems for some time yet.

18. TIRZAH, “Colourgrade”

Since her debut, this English author has been one of the Kalporz editorial team’s favourite voices. If Devotion had already raised various eyebrows for the maturity and the goodness of the compositions present, then with Colourgrade the artist has surpassed themselves. Applause for Tirzah’s class.

17. SNAIL MAIL, “Valentine”

With Valentine, the sophomore album by Snail Mail, Lindsey Jordan‘s maturation is total: her talent as a composer is evident everywhere, from the lacerating electric shocks of the song that gives the title to the album to the stealthy ‘Ben Franklin’, From the poetic romanticism of ‘Light Blue’ and ‘Mia’ to the liberating rock of ‘Madonna’ and ‘Automate‘. It is a record that talks about broken hearts and does it with determination and anger.

16. GENESIS OWUSU, “Smiling with No Teeth”

The debut album, among the funniest LPs of the year, for the twenty-three-year-old Ghanaian based in Canberra bewildered Kofi Owusu-Ansah (aka Genesis Owusu), Smiling With No Teeth entered without awe into the immortal funk / R & B trend that it took far too long to have a name of his own even in the ineffable Australia of the new century.

15. SUFJAN STEVENS & ANGELO DE AUGUSTINE, “A Beginner’s Mind”

Sufjan‘s delicacy is able to recreate itself in all its crystalline beauty with this Angelo De Augustine collaboration; becoming even lighter : not difficult personal themes but the musical representation of filmic snapshots. A conscious escape.

14. FOR THOSE I LOVE, “For Those I Love”

For Those I Love is the project of the Dubliner David Balfe, who on the debut of the same name deals with themes of love and loss (that of Paul Curran of Burnt Out, his best friend and poet like him, already honoured by Murder Capital) on an electronic and hip-hop basis, with samples of Smokey Robinson, Barbara Mason and Sampha. Deep like Automatic For The People, danceable like Original Pirate Material by The Streets.

13. ALTIN GÜN, “Yol”

At the time of the first album (On from 2018) the formula still had some very slight forcing. Moreover, already with the second album, the surprise effect – although not exhausted – was certainly reduced. But the new album travels surprisingly well. It pushes even further down the road of the Turkish wedding between a gleaming disco lady and a rather rough folkish gentleman. Yol is made up of coherence, emotional tension and the enhancement of a priceless heritage – the Turkish and Mediterranean one – which never seems to end.

12. JAZMINE SULLIVAN, “Heaux Tales”

In a genre like R&B it seems really impossible to come up with something new. But when there is the voice, texts that do not leave indifference and a quality of compositions then it can still be amazing. The Heaux Tales marks the great and surprising return of Jazmine Sullivan. Hit after hit and that’ not hyperbole.

11. JOHN GLACIER, “Shiloh. Lost for Words”

The twenty-six year old London rapper of Jamaican origins but raised in one of the “places to be” of artists and creatives – Hackney – on Shiloh. Lost For Words manages to condense the best sounds of the English underground into foggy tracks: between grime and R&B.

10. TURNSTILE, “GLOW ON”

It almost seems to be back to the crossover epic of the late 80s / early 90s, if it weren’t for the fact that GLOW ON has a contemporary language, the son of a melodic hardcore but which is highlighted in a lightning-fast pop, at the same time devastating and aesthetically flawless.

9. SEGA BODEGA, “Romeo”

With his work for Shygirl, the house producer NUXXE has defined one of the most powerful sounds heard in recent years, while his solo project presented a hybrid of songwriting, constantly evolving and convincing. Romeo, for this very reason, is a decisive step in the career of one of the most talented musicians of these times.

8. TYLER, THE CREATOR, “CALL ME IF YOU GET LOST”

Tyler offers a compendium of sounds and suggestions that differ more than ever, from gangsta-rap to trap, from contemporary R&B to nu-jazz in a sequence of at least ten potential singles that make CALL ME IF YOU GET LOST a mature work cohesive in its innumerable sound angles. Ideas, flows, compositions at the service of an innate talent that never ceases to amaze ten years on.

7. HELADO NEGRO, “Far In”

It was not easy to follow up on the excellent This Is How You Smile, released in 2019, but Far In is a victory. Roberto Carlos Lange packs a record that, taking up the themes and sounds of his predecessor, makes his own creative experience like a collective ritual. Through warm, familiar sounds and prominent collaborations, Lange invites us to look within ourselves to try to understand more of the world around us.

6. THE NOTWIST, “Vertigo Days”

As evidence of its intrinsic strength, Vertigo Days compiles a set of songs that follow one another as a single entity, and the lyrics, like poems on the problems of the world, our daily struggles and the cancellation of distance. Seven years of waiting have not been in vain.

5. L’RAIN, “Fatigue”

There was a time when all the most original and hard to label releases were Made in Brooklyn. We didn’t realize it, but a decade has already passed and thanks to artists like Taja Cheek that golden age seems to us a less remote past: psychedelic pop, soul, jazzy incursions and a very contemporary taste.

4. SHAME, “Drunk Tank Pink”

The second work of the London quintet, produced by James Ford (Arctic Monkeys), photographs youth alienation and depression at the time of the pandemic with greater ardor and angularity than on “Songs Of Praise”: highlights ‘Born In Luton’, punk-funk at the service nightmare, and ‘Snow Day’ with a vocal interpretation of Charlie Steen amidst jarring guitars to take your breath away.

3. BLACK COUNTRY, NEW ROAD, “For The First Time”

Before the album they won the title of “best band in the world” with little more than one song according to the English web-magazine The Quietus. With For The First Time Black Country, New Road prove to be a band that still has a lot to play, but which, for the first time, is capable of giving life to a new sound worthy of its influences. 2021 belongs to them.

2. LITTLE SIMZ, “Sometimes I Might Be Introvert”

It is a variegated and engaging disc, whose long duration allows, to those who do not yet know Little Simz, to fathom with a careful eye the art of the young rapper in almost every aspect: from the sources of inspiration to the virtuosity of the lyrics, from his magnetic voice to engaging and hypnotic rhythms.

1. LOW, “HEY WHAT”

An ambitious and sparkling work: with barely hinted guitar whispers, sudden roars, uncertain rhythms and lunar landscapes Low have always tried to give a shape to the void. An album aware of the fact that what is created can only be fragile, fragmented and limping.

KALPORZ AWARDS HISTORY (ex Musikàl Awards) :

Kalporz Awards 2020 (Yves Tumor)

Kalporz Awards 2019 (Tyler, The Creator)

Kalporz Awards 2018 (Idles)

Kalporz Awards 2017 (Kendrick Lamar)

Kalporz Awards 2016 (David Bowie)

Kalporz Awards 2015 (Sufjan Stevens)

Kalporz Awards 2014 (The War On Drugs)

Kalporz Awards 2013 (Kurt Vile)

Kalporz Awards 2012 (Tame Impala)

Kalporz Awards 2011 (Fleet Foxes)

Kalporz Awards 2010 (Arcade Fire)

Kalporz Awards 2009 (The Flaming Lips)

Kalporz Awards 2008 (Portishead)

Kalporz Awards 2007 (Radiohead)

Kalporz Awards 2006 (The Lemonheads)

Kalporz Awards 2005 (Low)

Kalporz Awards 2004 (Blonde Redhead, Divine Comedy, Franz Ferdinand, Wilco)

Kalporz Awards 2003 (Radiohead)

Kalporz Awards 2002 (Oneida)

Kalporz Awards 2001 ( Ed Harcourt)

You can catch the Monolith Cocktail’s choice albums of 2021 lists here:

Kalporz X Monolith Cocktail: [Scoutcloud] “Drommon”, Smote’s Acid-Folk Horror Spell

November 8, 2021

FROM OUR ITALIAN FRIENDS AT KALPORZ/ Monica Mazzoli

Continuing our monthly collaboration with the leading Italian music publication Kalporz , the Monolith Cocktail shares reviews, interviews and other bits from our respective sites each month. Keep an eye out for future ‘synergy’ between our two great houses as we exchange posts.

This month Monica Mazzoli introduces us to the music of bewitching acid-folk of Smote.

A sound experience: Smote‘s ‘Drommon’, initially released in April of this year only in the box by Base Materialism, is out this month on vinyl through Rocket Recordings in an expanded version: four tracks, instead of two, that sound as terrifying, as apocalyptic as if John Carpenter were producing an acid folk soundtrack to set to music a hypothetical remake of Brunello Rondi’s Il Demonio.

The studio project of Daniel Foggn, Smote is definitely one of the artists’ to watch out for in 2021: drone music, psychedelia and acid folk. On 21 November, they will make their debut live at Brave Exhibitions Festival as a full band (a quartet).

Monica Mazzoli can be found on Twitter.

Premiere: (Track) Antonio Raia & Renato Fiorito ‘Too Many Reasons’

October 19, 2021

PREMIERE SPECIAL/Dominic Valvona

In partnership with our Italian pen pals at Kalporz, both our sites have been chosen to simultaneously premiere the opening peregrination from the new collaboration between Antonio Raia & Renato Fiorito: the Thin Reactions album.

Eighteen minutes long, and taking up the entire A-side of that upcoming album ‘Too Many Reasons’ sees the amorphous saxophonist improviser and sound artist join together to capture the abstract atmospheres of cerebral reconnection; a sonic field in which to escape the stresses and weight of the pandemic.

Produced in lockdown, in the partnership’s native Napoli, this imagined space, in which a faded, fuzzy pining and wandering saxophone wafts around a rotated motorised humming and propeller purred windy and airy isolated soundtrack, brings together two experimental composers looking to create an ‘intimate and visceral experience’.

Although crossing paths years ago on site-specific performances and movie soundtracks, this traverse in tonal soundscapes marks the duo’s first fully released album together. They’ve chosen to deliver it on the new Italian label Non Sempre nuoce; the focus of which is on the burgeoning Neapolitan underground scene, covering, as the PR notes state, the city’s ‘post-clubbing music’, ‘Mediterranean retro sonorities’ and everything in-between.

Almost haunting in places, with field recordings that sound like a mysterious cyclonic desert, hinged fuzzes, vapours, fluted ambiguous regional sax and subtle little bursts of fizzled sonics are the only interruptions in this secluded landscape.

This is how the duo themselves describe this album venture: ‘Thin Reactions is an album consisting of sounds coming from invisible cities and intimate landscapes. It is a sonic trip you can take through a sensory experience. It is music that allows you to take a deep breath.’

You can now experience that immersive soundtrack below.

The Thin Reactions album will be released on the 29th October via the Non Sempre nuove imprint.

Kalporz X Monolith Cocktail: [Coverworld] ‘This Strange Effect’ From Nine Perfect Strangers

October 5, 2021

SONG THREAD/NETFLIX: Paolo Bardelli

Continuing our successful collaboration with the leading Italian music publication Kalporz , the Monolith Cocktail shares reviews, interviews and other bits from our respective sites each month. Keep an eye out for future ‘synergy’ between our two great houses as we exchange posts during 2021 and beyond.

This month Kalporz head honcho Paolo Bardelli shares a recent instalment of the site’s [Coverworld series], which runs through the history of a cover song made famous or brought into the public sphere by a contemporary artist (in this case, the recent Netflix hit show Nine Perfect Strangers).

Amazon Prime’s new TV serial Nine Perfect Strangers has a really good theme song by Unloved, a Los Angeles-based soundtrack trio made up of Jade Vincent, Keefus Ciancia and David Holmes. It’s called ‘Strange Effect’ and it’s not an original song (otherwise we wouldn’t be in this column…). More precisely, it is a cover of a 1965 song that has been remade several times.

‘This Strange Effect’ (yes, the original has that extra ‘This’) is a song written by Ray Davies of the Kinks but was first released by singer-songwriter Dave Berry in July 1965. Unloved’s reworking of the song (featuring the voice of Raven Violet, Keefus Ciancia’s daughter) is in line with the dreamy, drug-soaked feel of the series, where Dave Berry’s original is drier and the riff is played by a simple acoustic guitar.

But the Kinks also played it, though they did not officially release any studio version: there is, however, a readily available live recording of it at the BBC in August 1965, which was published in 2001 as the BBC Sessions 1964-1977. The Kinks’ interpretation is essentially identical in arrangement, only the sounds change.

Since then, ‘This Strange Effect’ has received several reinterpretations, the most “famous” being Hooverphonic‘s 1998 rendition, which is consistent with the Belgian band’s typical orchestral arrangements. In its elegance, the violins obsessively repeat those two notes to create a particularly hypnotic suspension effect. Hooverphonic released it as a single (for their album, Blue Wonder Power Milk) and were the first to demonstrate the ‘soundtrack’ capability of the track itself: it ended up in the film Shades (1999), in the TV series Nikita and for the American TV commercial for a Motorola mobile phone in 2005.

The following year, in 1999, the Thievery Corporation thought it best to make a mix of the Hooverphonic version that was almost unrecognisable, with the typical Thievery drumming and Arnaert‘s vocals standing alone at first and then, towards the end, rejoining the musical base of the other two Hooverphonic’s while still with the addictive rhythm of the TCs underneath.

The “ugliest” cover is the one by Bill Wyman, who included it for his 1992 album Stuff: there’s an annoying piano and little sounds that don’t even sound like the country church organ.

While the 2006 version by the Finnish band The Others is practically useless, the dreamy version, between sitar and harmonica, by the British band Squeeze is very histrionic and was included in the deluxe edition of their 2015 album, Cradle to the Grave.

Glen Matlock of the Sex Pistols also approached the song in 1980, with his project The Spectres: the result is interesting, between sax and a ‘Peter Gunn Theme’ style bass line:

A finally electric variant is Steve Wynn‘s on his 1997 album, Sweetness And Light: here how the song starts and shows its multifaceted, and not only “melodious”, soul. One of the most beautiful covers.

‘This Strange Effect’, on the other hand, comes back persuasive in the 2017 version by the Shacks, which has the only merit of ending up as the soundtrack of the iPhone TV commercial, because it has an annoying vocal pitch change in the verse and an incomprehensible speed-up on the ending. The Shacks are an American duo made up of Max Shrager and Shannon Wise, whose Follow Me I recommend listening to, which is very nice.

All in all, the Unloved’s version, although not new (it also appeared in the third series of Killing Eve) is one of the best, and has the merit of having given us the possibility of going through all the epic of this beautiful song from the sixties that still speaks to us.

(Paolo Bardelli)

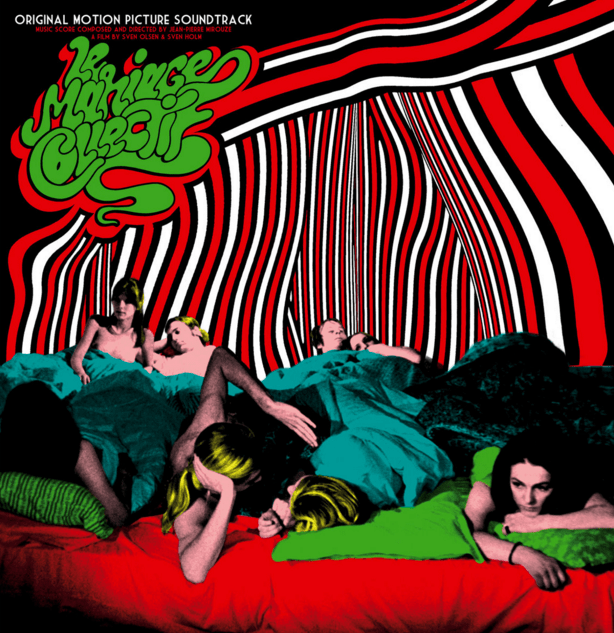

Kalporz X Monolith Cocktail: ‘Le Mariage Collectif’ (1971): The soundtrack found in a Parisian rubbish dump.

July 2, 2021

Album Review/Words: Monica Mazzoli

Continuing our collaboration with the leading Italian music publication Kalporz , the Monolith Cocktail shares reviews, interviews and other bits from our respective sites each month. Keep an eye out for future ‘synergy’ between our two great houses as we exchange posts during the 2021 and beyond.

This month Monica Mazzoli waxes lyrical on the chance rubbish tip find, the cult Le Mariage Collectif soundtrack.

The obscure fascination of certain music for the Cinema of the sixties and seventies seems to be endless: many film soundtracks have never been published (perhaps lost forever?) and continue to be shrouded in mystery. One thinks of the OST of Diabolik(1968) by Ennio Morricone, which seems to have been destroyed. The conditional is a must, of course.

Then, fortunately, there are also soundtracks that have been brought back to light and that often conceal stories to be believed: this is the case of the music of Les Chemins de Katmandou (1969) – one of the products of the collaboration between Serge Gainsbourg and Jean-Claude Vannier – recovered by the daughter of Vannier’s copyist (Daniel Marechal) and published in 2017 by Finders Keepers.

The medal for the world’s craziest vinyl-finding story, however, goes to the person who found in a landfill in Paris the acetate record copy of the soundtrack to Le Mariage Collectif, a 1971 film. The music for the erotic-hippie film directed by Sven Olsen and Sven Holm, composed by Jean-Pierre Mirouze and never released (except for the 45 rpm of ‘Together/Sexopolis’), is remarkable. Psychedelic instrumental moments alternate with funk and jazz passages. For Mirouze, it’s a bit of a return to his roots, he can experiment as he did in the early 1960s when, before working for television, he was part of the Groupe de recherches musicales (GRM) of the ORTF (the French national public broadcasting service), a group dedicated to the study of sound and electroacoustic music.

To Liberation in 2012, the composer said:

“I was mainly interested in the relationship between music and image. But at a certain point I had to find something that would make me live. I looked for work in television, where I found myself doing sound dressing, theme songs and small fleeting sound events” and, again, “I regret, however, the dispersion of the sound heritage of the time, the wonderful things that have been stolen from the ORTF sound library. Le Mariage Collectif is part of this wound, but there are many other things that will never be found”.

How can you blame him, perhaps a lot of material we may never hear. A pity.

The soundtrack to Le Mariage Collectif was released in 2012 by Born Bad Records, both on CD and vinyl. (Monica Mazzoli)

Our beloved pen pals at the Italian cultural/music site Kalporz celebrate the 80th birthday of Bob Dylan with Samuele Conficoni’s extensive interview with the Dylanologist Richard F. Thomas, the George Martin Lane Professor of Classics at Harvard University. Thomas discusses his essays about the bard ahead of the release of the Italian translation of his iconic tome Why Bob Dylan Matters: renamed Perché Bob Dylan for the Italian market.

Richard F. Thomas is George Martin Lane Professor of the Classics at Harvard University. He was born in London and brought up in New Zealand. He has been teaching a freshmen seminar on Bob Dylan since 2004 and writing essays about him for a number of years. One of his first contributions to the so-called “Dylanology” was his 2007 essay The Streets of Rome: The Classical Dylan (in Oral Tradition 22/1), where he tracked down references to Virgil, Ovid, Thucydides, and Italian literature within Dylan’s oeuvre. He is also the author of Why Bob Dylan Matters (Dey Street Books 2017), one of the most timely and exhaustive collections of essays about Dylan’s work ever written, which has been finally translated into Italian by Elena Cantoni and Paolo Giovanazzi with the title Perché Bob Dylan (EDT 2021). To quote a passionate thought expressed by Italo Calvino, a classic is a work – not necessarily a book – that “has never finished saying what it has to say”, that “’I am rereading…’ and never ‘I am reading….’.”

As a result, we can certainly agree that Bob Dylan is an artist of the same caliber as the ones usually studied in traditional academic courses. His influence on musicians, poets and novelists is impossible to be summarized. We are always re-listening and reliving his music while pondering on each single line, word or accent. His voice is a path for the Muses who are singing through him, as he said while finishing his brilliant Nobel Prize Lecture released in 2017. In the same Lecture, Dylan talked about some of the books which had inspired him the most, one being Homer’s Odyssey, the most ancient poem of Greek Literature along with the Iliad. It was not a surprise. Dylan started quoting the Odyssey in songs from his 2012 Tempest. Moreover, in concert, from 2014 onwards, he re-wrote ‘Workingman’s Blues #2’ (from Modern Times, 2006) in an extended way, making it his “personal” Iliad and Odyssey, and perhaps also his Aeneid. He also changed some of the lyrics for ‘Long and Wasted Years’ (from Tempest, 2012), adding a powerful quotation from Homer. Interviewed in 2016 by the Daily Telegraph, some weeks after being awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, Dylan said that some of his songs “definitely are Homeric in value”.

Although in Chronicles Vol. 1 (Simon & Schuster 2004) Dylan gave details about his early approach to Thucydides and Machiavelli, Suetonius and Tacitus, and in his 1974 ‘Tangled Up in Blue’ (from Blood on the Tracks, 1975) he sang about “an Italian poet from the 13th century”, specific references to Greek and Latin authors are somewhat recent within his oeuvre. However, as Thomas points out in his book, Dylan’s fascination for Rome probably goes back to his trip to Rome in 1962, after which he wrote the unreleased ‘Going Back to Rome’. Rome comes up also in ‘When I Paint My Masterpiece’, released for the first time on Greatest Hits Vol. 2 (1971). Moreover, in his 2001 La Repubblica interview, held in Rome, Dylan talked about ages in Hesiodic terms, and in a 2015 interview for AARP Magazine he said that, if he had to do it all over again, he would have been a schoolteacher in Roman history or theology. Just when you think you have figured out his art, he has already moved forward, and he doesn’t look back. Today, he celebrates his 80th birthday.

Samuele Conficoni had the pleasure of talking with Professor Richard F. Thomas about why Bob Dylan “is part of that classical stream whose spring starts out in Greece and Rome and flows on down through the years, remaining relevant today, and incapable of being contained by time or place”, and why he “long ago joined the company of those ancient poets.”

Professor Thomas, what are the aims of your seminar about Bob Dylan, which you started back in 2004, and why did you choose this particular approach to studying and teaching Dylan’s oeuvre?

The aims have evolved, as Dylan’s art has continued to evolve. When I started teaching it we didn’t have Modern Times, Together Through Life, Tempest, Rough and Rowdy Ways. So my aim of introducing a group of 18-year-olds to the entirety of Dylan’s oeuvre has become increasingly unattainable. Some of the students come in knowing Dylan, a handful have known him very well. But my aim from the beginning was connected to a desire that the students really get into the dynamics of Dylan’s songs, how they work on the records and in performance from all perspectives, musical, literary, aesthetic, cultural, political. You could do an entire seminar on each of these aspects, so the seminar cannot be comprehensive, but we cover the great periods in particular, including the recent decades. A first-year seminar, with students preparing a limited number of songs and presenting their findings to the group, seemed the ideal way of having a community of young people add Dylan to the centre of their canon, and that has worked over the years.

How would you present your crucial Why Bob Dylan Matters to Italian readers who will read it for the first time? I think it is one of the most essential books ever written about him.

I hope Italian readers will enjoy the book. Like Dylan, I was drawn to Rome and to ancient Italy as a boy, for me in New Zealand, about as far as you could get from Rome. Through the films of the late 1950s and early 1960s, a few years later than Dylan, but many of the same films, The Robe, Ben Hur, Spartacus, Cleopatra. I started Latin about the same time, partly because of those films, and haven’t looked back. It was my main ambition to have the book appear in Italian, because that’s where large parts of it too were born. In Italy there is a respect for song and poetry and poetic traditions, obviously with Dante, poet of l’una Italia at the center, but going back through him to Virgil and forward through him to Petrarch and everything that followed, all the way up to Bob Dylan. Dylan realizes all of this, as he said in the Rome interview in 2001. That is in my view one reason he did those two spectacular, unique performances at the Atlantico in Rome on November 6 and 7, 2013. I write about how he was bidding farewell to more than a dozen of the songs he sang those two nights there in Rome, as a gift offering to the city, singing some of them for the last time.

Rome and Italy are in Dylan’s blood, going back to his boyhood and the Roman experience of his teens, and now alive and vital in his late 70s, from the Rubicon to Key West in the imagination of his new songs. I was able to get to Italy three years ago, in the early April spring of 2018, after the book came out, where I saw him at the Parco della Musica in Rome, and in Virgil’s native town of Mantua, across the Mincio in Palabam Mantova, now the Grana Padano Arena. That was a magical experience, the songs of Bob Dylan in the hometown of Virgil. During the day I made my usual pilgrimage to the medieval statue of Virgil at his desk, also from the 13th century, carved in the wall of the Palazzo del Podestà, to Mantegna’s stunning frescoes in the Camera degli Sposi, to Ovid and his Giants in the Palazzo Te, and to the fascist Virgil monuments in the Piazza Virgiliana. Then from Virgil by day to Dylan at night, his setlist including ‘Early Roman Kings’ and so taking me back to the daytime activities. I hope a lot of that comes through in the book.

How do your essays fit within Dylanology, particularly in relation to other influential contributions such as those by Christopher Ricks and Greil Marcus?

I’d be honoured to have my names next to those two. Marcus’ work on the deeply American traditions of Dylan’s music, from the late 1960s in Invisible Republic to the more recent work on the place of the blues, in music and well beyond, are among the most important contributions, and not just to an understanding of Dylan. Christopher Ricks in a way made it OK to work on Dylan as an academic topic. Bob Dylan’s Visions of Sin lays out the ways in which Dylan belongs in the centre of the literary traditions of the last two or three centuries, particularly the 18th and 19th. His engagement with the holistic elements of Dylan’s song poetics in his analysis of the rhymes, prosody and meaning of “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” is magnificent. My book is somewhat different in its emphasis on more deliberate forms of intertextuality, involving Dylan’s verbatim use of authors, mostly but not only from classical antiquity, and in the way that the songs inhabit and become part of those traditions, bring them into the land of the living through his art.

I was interested in the new and profound ways in which, especially in the songs of this century, Dylan’s songwriting engages in what he has called “transfiguration.” That is something he has always done with the traditions of folk, as he pretty much spelled out in the Nobel Lecture in June 2017. There he spoke of picking up and internalising the vernacular, but the way he describes that process is notable: “You’ve heard the deep-pitched voice of John the Revelator and you saw the Titanic sink in a boggy creek. And you’re pals with the wild Irish rover and the wild colonial boy.” Heard, saw, pals with. That early transfiguration through the intertextual process leads to a parallel outcome with the classical authors, but more. When he sings “No one could ever say that I took up arms against you”, the singer of “Workingman’s Blues #2” becomes the exiled Ovid, whose precise words Dylan gives to the singer. When the singer of “Early Roman Kings” quotes verbatim the taunt of Odysseus triumphantly hurled at the blinded Polyphemus from a specific translation of the Odyssey—“I’ll strip you of life, strip you of breath / Ship you down to the house of death”—that singer becomes Odysseus. But the singer was also “up on black mountain the day Detroit fell”, his 2500-year old transfigured singer also alive in the racial discord of the 20th century. So I suppose that tracing this role of intertextuality was one of the contributions of my book.

I have been studying Bob Dylan, the Classics, and Italian literature for many years. I have always found it wonderful to see how skilled and original Dylan is in connecting such disparate authors within his compositions. Nobody sings Dylan like Dylan, it is true, but I would go further and say that nobodywrites like Dylan. How does Dylan “handle” his sources?

Yes, nobody writes like Dylan, as nobody in his art or anywhere in living creative practice reads or thinks like Dylan. Virgil, Dante and Milton did, and so did Eliot. Dylan has an eye for the poetry of language, as he encounters it in the eclectic reading and listening he does. Take the lines from verse 6 of “Ain’t Talkin’”, on the Modern Times album version, but not to be found in the official lyrics book: “All my loyal and my much-loved companions / They approve of me and share my code / I practice a faith that’s been long abandoned / Ain’t no altars on this long and lonesome road”. The first three lines come from three different poems in Peter Green’s translation of Ovid’s exile poems, as a number of us have recorded. Individual lines (Tristia 1.3.65, “loyal and much loved companions”; Black Sea Letters 3.2.38 “who approve, and share, your code”; Tristia 5.7.63–4 “I practice / terms long abandoned”) lifted from across 150 pages in the Penguin translation. And the altars on that long and lonesome road belong to the world of the blues pilgrim but also to Ovid’s world where roadside altars were a fixture from the Appian Way to the Black Sea. Nobody but Dylan could pick up that book and produce that sixth verse, completely at home in the song whose title started out its life in the chorus of a Stanley Brothers bluegrass song, “Highway of Regret”: “Ain’t talking, just walking / Down that highway of regret / Heart’s burning, still yearning / For the best girl this poor boy’s ever met.” And that is before we even start to trace the other intertexts: Poe, Twain, Henry Timrod, Genesis and the New Testament Gospels. Peter Green created poetic lines in his response to Ovid’s poem: “a place ringed by countless foes”, “May the gods grant … that I’m wrong in thinking you’ve forgotten me”; “every nook and corner had its tears”; “wife dearer to me than myself, you yourself can see”, and so on. Dylan took those lines and used them, just a few in each of the songs, and made them part of his own fabric—in one case even becoming a song title: “beyond here lies nothing”. As with the intertextuality in the hands of those other great artists, the lines he successfully steals and renews bring with them, once we recognise the source, their Ovidian setting, a poet in exile, in place or in the mind, getting on in years, “in the last outback at the world’s end.”

Also as with all great literature, Dylan is way ahead of the critics, or far behind his rightful time, which is to say the same thing. Early on there were even critics who denied the presence of Ovid in the song and on the album, partly because they just found any old Ovid translation online, and then the transfiguration doesn’t work. You have to work from the translation Dylan was using, the Penguin, as he used Robert Fagles’ Penguin of the Odyssey on Tempest. And a lot of people don’t like the idea that Dylan’s songs are composed out of the fabric of other materials, discrete as they are on this song. That is a throwback to Romanticism, to Wordsworth’s notion that poetry is a “spontaneous overflow of emotion”, though that was never true, even for Wordsworth. I have no problem with intertextuality and transfiguration, because that is how my other poets worked, in antiquity and down through the Middle Ages and Renaissance to the end of the 18th century in the Latin and vernacular literary traditions.

Virgil’s incisive “debellare superbos”, “taming the proud”, from Aeneid VI, comes up in Dylan’s “Lonesome Day Blues”, from his 2001 masterpiece “Love and Theft”, and a fascinating allusion to the Civil Wars (whether they be Roman or American) appears on “Bye and Bye”, which is from the same album. On Rough and Rowdy Ways, Dylan seems particularly fond of Caesar, who is directly mentioned in “My Own Version of You” and whose presence hovers around “Crossing the Rubicon”. What is Dylan trying to convey with those references?

Bob Dylan has been familiar with Julius Caesar at least since March 15, 1957 whether or not he remembers that spring day when the 15-year-old and the Latin Club of which he was a member published a paper commemorating those Ides of March up in Hibbing. By then his mind was more on the bookings his band The Golden Chords had at Van Feldt’s snack bar, but it is a historical fact, as I show, that he and the Roman dictator were acquainted early on. Shakespeare’s play could have helped the relationship since he had probably seen Marlon Brando playing Marc Antony in Joseph L. Manckiewicz’s 1953 movie version of the play. To be sure, that film, which returned to the State Theater in Hibbing on February 9, 1955, may well have been one of the reasons he enrolled in Latin the next fall. Who knows?

Dylan has always been interested in civil war, and was a historian of the American Civil War long before 2002 when he wrote and performed “’Cross the Green Mountain” for the 2003 film Gods and Generals. Around the same time in Chronicles, Volume 1, he talks about that seminal American conflict in ways that suggest he has long been inhabiting the middle of the 19th century in his mind, to the time when in his words “America was put on the cross, died, and was resurrected.” And the consequence of that inhabiting cannot be understated, as he continued, “The godawful truth of that would be the all-embracing template behind everything that I would write.” Dylan quite perceptively sees in the southern plantation owners a mirror of the “Roman republic where an elite group of characters rule supposedly for the good of all” (Chronicles 84–85). Here he is again going back to Rome, as throughout his life.

By the time of Chronicles he had already conflated the American Civil War with its Roman versions, by combining Virgil’s Aeneid and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in “Lonesome Day Blues”, and yes, on the same 2001 album, by allusions in “Bye and Bye” (“I’ll establish my rule through civil war”) and maybe in “Honest with Me” (“I’m here to create the new imperial empire”). His interest continued in “Ain’t Talkin’” in 2006 where the connection to Rome is undeniable given how much Ovidian poetry there is on the song (“I’ll avenge my father’s death then I’ll step back”). Here he channels Caesar’s adoptive son, the first Roman emperor Augustus, who said in his own memoir “Those who killed my father I drove into exile, by way of the courts, exacting vengeance for their crime . . . I did not accept permanent the consulship that was offered to me.” He returned to this shared civil war and Caesarian theme—and to the hills of Rome perhaps—in 2012 in “Scarlet Town” (“In Scarlet Town you fight your father’s foes / Up on a hill a chilly wind blows”). I wrote about all of that in the book. And now there he is again in 2020, in “My Own Version of You”, a song that’s all about intertextuality, asking himself, “what would Julius Caesar do”—and of course crossing the Rubicon, the signature act of Julius Caesar. Dylan is also interested in assassination of course, President McKinley in “Key West” and John Fitzgerald Kennedy in “Murder Most Foul”, so it’s not surprising that Dylan, who said if he had to do it over he would teach Roman history, has returned to Caesar. Of course, in “Crossing the Rubicon” it’s not just a theme, he’s become Julius Caesar, transfigured as he takes that fateful step at the end of each verse. As he so he fulfils the prophecy made in the Rolling Stone interview with Mikal Gilmore in 2012: “Who knows who’s been transfigured and who has not? Who knows? Maybe Aristotle? Maybe he was transfigured. I can’t say. Maybe Julius Caesar was transfigured.”

Alessandro Carrera, another relevant Dylan scholar and Professor at the University of Houston, has recently written about why Dylan often refers to Homer’s Odyssey from 2012 onwards. He thinks that Dylan’s metaphorical exile, represented by his references to Ovid’s later works (Tristia and Epistulae ex Ponto) in Modern Times (2006), ended. He is now facing his nostos, he is “slow coming home”, as he sings in “Mother of Muses” (2020). In his opinion, the rewritten lyrics for “Workingman’s Blues #2” well represent his personal relationship with both Iliad and Odyssey. What is your view about that?

Yes, certainly the Odyssey, as I discussed when I wrote about those lyrics changes to “Workingman’s Blues #2”. I’m not sure how much Dylan has engaged the Iliad yet, though the Nobel Lecture brilliantly picks up on the Odyssey’s questioning of the heroic code of the Iliad, and of the shade of Achilles in the Underworld realizing that the quest for honor and glory was empty, that being alive was what mattered. Dylan has the Achilles tell “Odysseus it was all a mistake. ‘I just died, that’s all.’ There was no honor. No immortality.” That, by the way, is as brilliant a piece of intertextuality as you’ll find anywhere.

Yes, of course, nostos, and the return home. We’re all doing that, but home has shifted. Not Ithaca or Hibbing anymore, but a different home. That’s why Dylan includes Porter Wagoner’s great country song “Green Green Grass of Home” among the songs that had taken on the themes of the Odyssey. The singer imagines being back home, but in reality he’s in prison, about to walk at daybreak to the gallows with the sad old padre. They’ll all come to see him when he’s six feet under, under the old oak tree that he used to play on before his life went astray, maybe the same oak tree the singer of “Duquesne Whistle” remembers. You can’t actually come home. Dylan, like many poets going back to Homer, knows that. And that’s why, as I wrote in the book even before “Mother of Muses” came out, I suspected Dylan had been reading and channeling the great Greek poet of modern Alexandria. For Cavafy, the return to Ithaca is what is important, the living of life itself. The lines in his poem “Ithaca” tell that the island is just the destination, “Yet do not hurry the journey at all: / better that it lasts for many years / and you arrive an old man in the island.” That’s what comes to me at the end of Dylan’s “Mother of Muses”: as for Cavafy, so for Dylan and the rest of us, no reason to hurry that journey. “I’m travelin’ light and I’m slow coming home.”

What do you think of Bob Dylan as an historian? His way of reviving, rewriting and often changing the history is brilliant and meticulous. Does Dylan remind you of any Greek or Latin historiographers?

Of course, Bob Dylan isn’t a historian in the modern sense, in getting to some absolute factual truths. His early songs, perhaps reflecting some of the less imaginative teaching to which he may have been exposed, made that clear: “memorizing politics of ancient history / flung down by corpse evangelists” and “the pain / of your useless and pointless knowledge.” But it is interesting that he has in more recent years been mentioning ancient historians and thinkers, Thucydides, Cicero, Tacitus, since he shares with them outlooks about historiography of a more creative type. “History” contains “story”, and in Italian of course the word for history is precisely that, storia. Ancient historiography expected not so much truth—so often beyond reach—as believability, to be achieved, so said Cicero, by constructing the elements of the story, as with a building. Even the relatively factual Thucydides reports verbatim speeches he did not hear, along with those he did. The speeches he composes assume they would have been what was said, given the events that followed on the words. If those actions, then necessarily these words.

There is an element of storytelling here, putting together what must have happened. Likewise for Tacitus, whom Dylan mentions on various occasions, and who writes of Nero’s killing of his own mother, Agrippina: “The centurion was drawing his sword to kill her. She thrust out her stomach and said “Hit the belly!” and was finished off.” How did Tacitus know what she said? The matricide happened when he was about three years old. But it’s believable and it sounds good, and Tacitus, like Dylan, would have said you want your history to sound good. Take the historical ballad “Hurricane” about the murder trial of Rubin “Hurricane” Carter. Did the cop really say of one of the victims, “Wait a minute, boys, this one’s not dead”? Probably not, but he could have, it’s believable, and more important it sounds good. In both cases the wording puts you right there at the scene.

So yes, songwriting has aspects of this old storytelling historiography. In a sense, folk songs, particularly ballads, are a form of oral history: “Robin Hood and the Butcher”, “The Earl of Errol” “Rob Roy”, “Dumbarton’s Drums”. Dylan’s versions are just updates, putting into story historical events of his own finding, sometimes from the obscurity of newspaper clippings or archives—“The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” and “Joey” about the deaths of two historical people. It doesn’t matter whether or not William Zanziger had a “diamond ring finger” or Joe really saw his assassins coming through the door “as he lifted up his fork”. Both are plausible, and both help paint a picture, or “finish off a building” (exaedificatio), the metaphor Cicero used for fleshing out the narrative.

“Ut pictura poësis” (“Poetry is like a painting”), Horace wrote in his Ars Poetica (Epistula ad Pisones). Back in 1974 Bob Dylan was deeply influenced by Norman Raeben, a New York artist who gave him painting lessons. Dylan himself is also a good painter. Do you think we could link Horace’s maxim to Dylan’s song composition?

As you know, Horace also goes on to elaborate the ways poetry, or let’s say songwriting, is like painting: some repays getting close up, some from standing back. He also distinguishes the poem/painting that you can look at/read just once, and the ones you can never get enough of, keep coming back to. Dylan’s songs are generally of that sort, you can keep coming back to them, never tire of them, especially as he changes the arrangement and performative dynamics from year to year and night to night. Dylan’s painting, and his sculpture, are very interesting. I need to see more of it and think more about it. I’ve had the experience of seeing the Mondo Scripto lyrics and drawings on a couple of occasions. I actually thought of Horace on getting up close during those experiences. There is something quite moving about being up close to the depiction of a scene from a particular song, juxtaposed with Dylan’s handwritten lyric. You’re reading, viewing, and also silently hearing the song in your head. This can produce an interesting synaesthesia, a productive mingling of the senses. As for Raeben, Dylan has of course spoken of him, and he and his teaching were clearly important for Dylan’s painting career. Critics talk of the impact on the songs of Blood on the Tracks, the visuality of lines from “Shelter from the Storm” and especially “Simple Twist of Fate”.Enargeia, the Greeks called it, vividness, and the ability to paint a picture in words. But that quality is already there in 1966 in “Visions of Johanna”. Who taught Dylan to write like that? The Muses, of course, as he finally came out and revealed on the new album.

In his significant 2001 Rome interview, Dylan deals with lots of topics, and one of the subjects which has always caught my attention, as you pointed out in your essays, was his reference to the “ages” of the world in Hesiodic terms. At some point the discussion fades out and another subject comes up. It seems that Dylan almost deflected the argument or was not in the mood for explaining his theory. What do you think Dylan means when he speaks about that? Does this theme come up in some of his songs?

Well, as you know, I write about that Rome interview in the book, though there is more to be said on that topic perhaps. Dylan actually mentions all of the five ages that appear in Hesiod’s Works and Days: the Golden Age, the Silver Age, the Bronze Age. Then “I think you have the Heroic Age someplace in there” and next “we’re living in what some people call the Iron Age.” That’s a pretty precise reference to Hesiod, the only ancient poet to have an age of Heroes along with the metallic ones. In Hesiod that’s probably a reference to the Homeric texts and the heroes who fight and die at Troy.

I don’t know why Dylan brought that up, but the journalists missed whatever point he was making. He finished with a non-classical reference maybe to deflect from those precise allusions: “We could really be living in the Stone Ages.” That gave the opening to a journalist who joked: “Living in the Silicon Age”, and so the moment was lost, the shooting star slipped away, as Dylan replied “Exactly”—in other words “you didn’t get it”—then “Silicon Valley.” I’ve often wondered what would have happened if one of the reporters had known what Dylan knew, and had asked “How do Hesiod and his metallic ages come into your songwriting?” Of course he could have deflected that too, as when one of them earlier in the press conference asked about new poets he was reading and got the reply “I don’t really study poetry.” So we’ll never know, but I do think he has been interested in the Greco-Roman ages, at least since the late 1970s. There are Tulsa drafts of “Changing of the Guards” that suggest he was reading Virgil’s messianic fourth eclogue, about turning the ages back and getting from the iron age present to the golden age utopian past. That’s where Jupiter and Apollo in the published version of the song come from, having survived the drafts.

In 2020 you published an essential journal article, “’And I Crossed the Rubicon’: Another Classical Dylan” (in Dylan Review 2.1, Summer 2020), which represents the natural continuation of Why Bob Dylan Matters. In this article you deal with “the classical world of the ancient Greeks and Romans in the songs of Rough and Rowdy Ways”. What “kind” of classical world did you find there?

Dylan himself points to what the album does with the ancients in the last interview he has done to date, with Douglas Brinkley in the New York Times of June 12, 2020. He did the same in advance of the release of “Love and Theft” at the Rome Press Conference in 2001, hinting at the presence of Virgil on that album: “when you walk around a town like this, you know that people were here before you and they were probably on a much higher, grander level than any of us are.” I don’t know why Brinkley in 2020 asked Dylan about “When I Paint My Masterpiece”: why did Dylan “bring it back to the forefront of recent concerts?” His response to that one was also a tell-tale sign, in this case about the album he released the next week: “I think this song has something to do with the classical world, something that’s out of reach. Someplace you’d like to be beyond your experience. Something that is so supreme and first rate that you could never come back down from the mountain. That you’ve achieved the unthinkable.”

The classical world on the new album, as I set out in the Dylan Review, is not so much a verbatim transfiguring of the ancient world, but a more freely creative version, “my own version of you.” So the cypress tree where the “Trojan women and children were sold into slavery” in the song, as I noted, comes from Book 2 of the Aeneid, but unlike the use of Ovid and the Odyssey, Dylan is not quoting from known translations, but doing his own version. I’ve gathered most of the material on the other songs, “Crossing the Rubicon”, “Mother of Muses”, “Key West”. So I won’t repeat that here. It’s a free online journal, though accepts contributions. On those songs you can see Dylan has scaled those mountains of the past he also sang about in “Beyond Here Lies Nothing”. My guess is part of him will stay up on the mountain, as I certainly have myself!

In the same article you wrote that the “intertextuality that has been a hallmark of Dylan’s song composition since the 1990s continues on the new album”…

Yes, I did, and it’s true. But it’s a freer version, more like that of Virgil or Ovid themselves, or Dante, Milton and Eliot, not quoting and juxtaposing—Virgil with Mark Twain and Junichi Saga in “Lonesome Day Blues” or Ovid and Henry Timrod in “Ain’t Talkin’”; rather channeling ideas and creating reconstructed worlds into his own new world: the singer of “Crossing the Rubicon” could be Julius Caesar on that day that went down in infamy as the Roman general destroyed the republic, as he “looked to the east and crossed the Rubicon”. That is the direction Caesar would have crossed the river that goes gently as she flows north into the Adriatic. But you won’t find the line in Suetonius’s Life of Julius Caesar, or in Caesar’s own history of the Civil War. Along with the classical world the song tells us the “Rubicon is the (not “a”) Red River”, taking us back through Dylan’s 1997 song “Red River Shore”, which itself takes us to the Red River of Dylan’s native northern Minnesota and the Texan Red River Valley of the Jules Verne Allen song that Gene Autry sang in the movie of the same name. That’s just a tiny part of the intertextuality of Rough and Rowdy Ways, ancient and modern alike.

As I have already mentioned, on Modern Times, Dylan refers to a lot of verses from Ovid’srelegatio works (Tristia and Epistulae ex Ponto). In “My Own Version of You”, from Rough and Rowdy Ways, he sings of the “Trojan women and children” who “are sold into slavery”, and you notice that he is not referring to Euripides’s play The Trojan Women but rather to Virgil’s Aeneid II. What is Dylan’s journey? Is he still “a stranger here in a strange land”, as he sang in 1997 in “Red River Shore”?

Who isn’t? If the past is a foreign country, just by living on in time we all remain strangers in a strange land, where nothing looks familiar. But Dylan’s creative memory allows us to go back with him and straighten it out, recreate worlds that embrace our own lived experiences—worlds that contain multitudes. Dylan’s journey is a life, or multitudinous lives, in song, and it’s been a pleasure for countless thousands of us to have sailed, and be sailing, with him on that journey.

“I’ve already outlived my life by far.” So says the singer of “Mother of Muses”, sounding like Virgil’s Sibyl, who is given long life by Apollo, but without eternal youth, which is what makes her human and like the rest of us. That’s just another way of being a stranger here in a strange land, with time and space pretty much interchangeable. That’s also just one of the ways Dylan’s always written and sung our songs for us.

(Samuele Conficoni)

Kalporz X Monolith Cocktail: Minor Moon ‘Tethers’

April 29, 2021

Album Review/Words: Paolo Bardelli

Continuing with our collaboration with the leading Italian music publication Kalporz , the Monolith Cocktail shares reviews, interviews and other bits from our respective sites each month. Keep an eye out for future ‘synergy’ between our two great houses as we exchange posts.

This month Paolo Bardelli introduces us the music of Sam Cantor, aka Minor Moon.

Minor Moon ‘Tethers’

(Ruination Record Co./Whatever’s Clever, 2021)

Is Chicago still the centre of the world? There was a time when people wondered, and that was the time of Obama, who was based there: it seemed that the ferment united everything, from intellectuals to musicians. Sam Cantor from Chicago and his Minor Moon project, now in its third chapter, seems to be one of those who take the baton and ferry the city, or at least its sound, towards better times, in a quiet way. It is no longer the time to make waves: Minor Moon’s delicately psychedelic folk looks back to American rock but with grandmotherly care, that attention to substance which is typical of those who know what is important. But more than anything else she knows that it matters to have good songs to play with passion and protection.

Comparisons with better known names to show where this cosy Tethers is heading could be to compare it to an Iron & Wine with a few straws, or a Cass McCombs with fewer edges, but it would perhaps be ungenerous towards Sam Cantor who has reached a degree of autonomy that does not deserve to be “what he looks like”. Not least because it doesn’t sound like anyone but an idea that folk rock can still be done with grace and tradition that looks to the past to move forward.

If the songs were all like the opening ‘Ground’, a song that greets you like a friend would when you’re in trouble, or the cosmic folk tracks of ‘Under an Ocean of Holes’, we’d be talking about a near-masterpiece, but of course there’s a bit of everything: the pop of ‘Hey, Dark Ones’, the nocturnal ballad ‘Beyond The Light’, the deep States of ‘Was There Anything Else?’. All this is well amalgamated for the 36 minutes that are the time of an album from the past, the ones that used to be on the side of a C90.

But Minor Moon are just like a moon of the future, slyly looking at us with lunar times, not earthly ones.

71/100

(Paolo Bardelli)