Kalporz X Monolith Cocktail: [#tbt] Music for growing houseplants

October 26, 2023

A FOCUS ON THE JAPANESE COMPOSER HIROSHI YOSHIMUR FROM OUR FRIENDS AT Kalporz

AUTHORED BY Viviana D’Alessandro

Hiroshi Yoshimura (1940-2003)

Continuing our successful collaboration with the leading Italian music publication Kalporz , the Monolith Cocktail shares reviews, interviews and other bits from our respective sites each month. Keep an eye out for future ‘synergy’ between our two great houses as we exchange posts during 2023 and beyond. This month, Viviana D’Alessandro hones in on the music of electronic minimalist progenitor Hiroshi Yoshimura for the site’s #tbt series.

The Japanese 80s gave music history one of the pilot moments in the formation of ambient music. If we have recently worked in this space to understand the experimental roots of relaxed music , this week’s #tbt has the ambition of setting sail towards the Rising Sun.

Artists such as Hiroshi Yoshimura , Midori Takada , Satoshi Ashikawa are spurious children of the rampant economic growth of post-war Japan, but produce soundscapes that are introverted and aesthetically averse to the urban imagination, directly taking up or simulating the complex relationship of Japanese culture with the natural world.

Kankyō Ongaku: Japanese Ambient, Environmental, & New Age Music 1980-1990 (Light in the Attic Records)

An example above all is Green (1986), the fifth work by composer Hiroshi Yoshimura and a founding pillar of minimal ambient. Recorded amidst the hustle and bustle of what we imagine to be a rapidly changing Tokyo, the record’s pristine stillness offers a line of escape to the noise of heavy vehicles, jackhammers and clanging metal objects that would have dominated the natural soundscape at the time of the city. Even the album cover – a beautifully photographed apartment Schlumbergera – conveys this purity of sound.

Yoshimura identified his work as “kankyō ongaku” ( environmental music ), which we could certainly define as the Japanese version of ambient but with a very different slant: where Brian Eno , for example, created music for a constructed and imaginary environment as in Music For Airports (1978), Yoshimura and his contemporaries created music for extremely specific and tangible places.

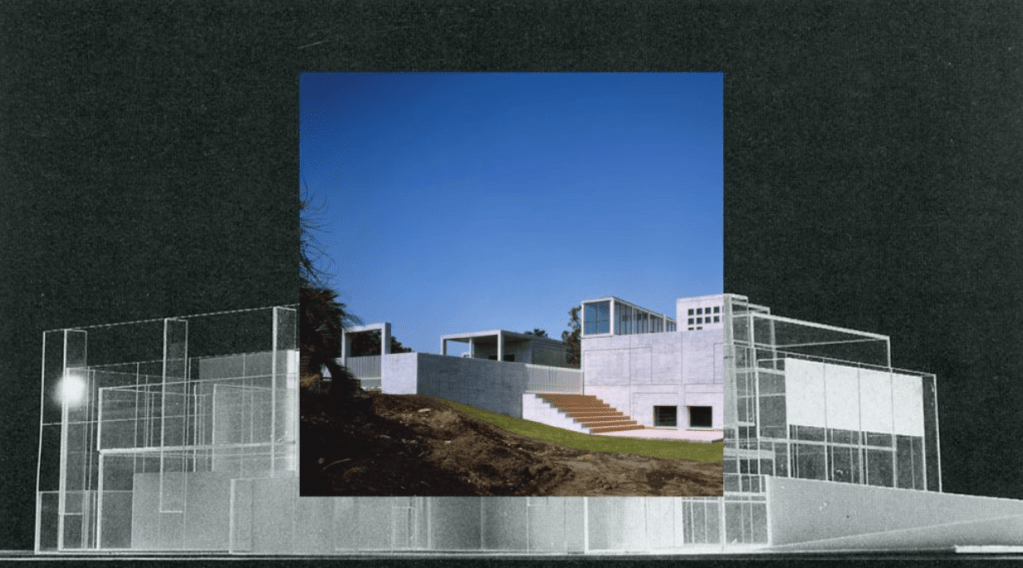

A good example is Surround from 1986 (soon to be reissued by Temporal Drift), born at the request of the real estate company Misawa Home and designed to curate the soundscape of their model homes. Or the debut Music For Nine Postcards (1982), composed in direct response to the Hara Museum of Contemporary Art. Like Eno, however, Yoshimura rooted his approach in French composer Erik Satie ‘s concept of musique d’ameublement (furniture music) , music that fits into the sonic context of the environment and does not require careful listening. Eno made direct reference to Satie in Discreet Music (1975), while among these artists it was Satsuki Shibano in 1983 with Erik Satie (France 1866-1925) who traced a more explicit Paris-Tokyo axis.

While these records were designed for particular spaces, they were also deeply evocative. The simulation of an idyllic-bucolic place is definitely something very present in these works, and it becomes almost saturating when returning to Yoshimura’s “Green”. A noteworthy aesthetic position considering that the album was composed mostly using a Yamaha DX7 , a synthesizer commonly known for its artificiality. “The DX7 is not a natural sounding instrument at all, it’s very digital. The way he can make something sound so natural on that instrument is amazing” – says Allen Wooton (aka Deadboy), interviewed about the record for FACT magazine – “it’s as if someone had studied the world natural was then able to somehow replicate its aesthetics”. It is interesting to note, by the way, that the reference to the colour green in the album’s title refers not to a chromatic nuance, but rather synaesthetically to a phonetic imagery, a natural extension of sound space through the inclusion of natural sounds in modern life. The album cover itself reads GREEN as a double acronym: Garden / River / Echo / Empty / Nostalgia; Ground / Rain / Earth / Environment / Nature.

It is perhaps no coincidence therefore that “Green”, despite being conceived in a period of rampant industrialisation, still preserves an underlying optimism. All eight compositions on this album present sublime layers of character and tones suspended with a minimalist resistance that survives the nuances of modern reality, but doesn’t complain about it. A prescient anti-Luddism considering that until the end of the 1910s the works of Yoshimina, Takada and Ashikawa were practically unknown to posterity and were resurrected thanks to the Youtube algorithm. Spencer Doran of the electronic duo Visible Cloaks, of all people, has taken it upon himself as a great collector of Japanese music to curate an incredible series of mixes for Root Strata.

For now we’re inclined to take this as a good sign, given that the appeal of these ’80s ambient LPs is their focus on improving and changing existing ecosystems. Rather than offering respite in the form of escape – as a classic interpretation of ambient music would have it – many of these Japanese artists practiced sound design as a way to integrate or alter physical locations into spaces of serenity, stillness, and infinite possibility.

Our Daily Bread 287: R. Seiliog ‘Megadoze’

November 14, 2018

Album Review/Dominic Valvona

R. Seiliog ‘Megadoze’ (Turnstile Music) 30th November 2018

The Welsh producer’s most cerebral and tactile electronic evocations yet, Robin Edwards’ (under the mantle of his R. Seiliog moniker) new album subtly pushes out into the expanses of a naturalistic imbued void with a depth and patience seldom heard outside the fields of ambient and new age music.

Echoing the trance-y and controlled build-ups of techno’s burgeoning creative epoch in the early to mid 1990s – especially the likes of Seefeel, Sun Electric, Beaumont Hannant and, well, a fair share of the Warp and R&S labels output in that period – Edwards ‘ambisonic’ visions shift seamlessly between the mysterious and radiant; weaving together elements of Kosmische, minimalism, intelligent techno and even psychill into wondrous soundtrack of discovery.

Megadoze is in no way, as the title might suggest, one big somnolent snooze fest; even if there is a lot of suffused ambience to be found, and tracks take an unhurried amount of time to unfurl their brilliance and scope. The minimalist whispery, silvery and peaceable ‘DC Offset’ (a reference to ‘mean amplitude displacement’ too lengthy to discuss here) for example bears traces of The Orb and David Matthews, yet also features the sort of downplayed beats and rhythms associated with sophisticated dance music. In fact, no matter how gentle or languid, each track features constantly stimulating and evolving textures of metallic and crisp, whipped beats amongst the vapours, undulations, drones and waveforms.

A manufactured wilderness and cosmos, Megadoze sounds like Autechre rewiring The Future Sound Of London and Steve Reich: Imagine cascading waters, volcanic glass, the dewy lushness of fauna and awe of the constellations organically shining or ringing through omnipotent machinations and the itchy, pitter-patter of computerized, sequenced drums.

In many ways a 90s album thrust into the next century, produced on more sophisticated apparatus; Edwards’ brand of nuanced electronica is rich with the possibilities of both eras. His most ambitious work to date, Megadoze is alive with ideas and tactile sensibilities, a moody record that can, over time, open-up with wonder and radiant magic.