A world of sonic/musical discoveries reviewed by Dominic Valvona. All releases are featured in alphabetical order.

Audio Obscura ‘As Long As Gravity Persists On Holding Me to This Earth’

20th May 2025

Slipping in and out of realities and consciousness, between field recordings of nature with its birdcall choruses and the metallics, oscillations of the electronically engineered and synthesized, Neil Stringfellow – aka Audio Obscura – offers a liminal balance of sound collage, melody, and the alien drawn to a both felt and metaphorical gravitational pull on his first album in just over a year.

Returning after a fallow period of sonic recording with a new creative impetus – spending a good part of last year gigging heavily, with notable performances in Poland and at Switched On in Whitby –, As Long As Gravity Persists On Holding Me to This Earth is just the first of a number of releases due out this year – the Mortality Tables label has offered Stringfellow a platform for a new project in September. And it at least in part maintains a connection to last year’s brilliant hagiography album, Acid Field Recordings: the avian signatures and passages that seem near hallucinogenic; the subtle use of underlying or undulated soft beats. The elements of electro and trippy trance-y dub however are not so obvious: don’t get me wrong, you can still pick out evocations of The Orb, FSOL and Amorphous Androgynous. Instead, there is a new found beauty of moving classical strings, more piano and melodious qualities to be found in an amongst the tangible and intangible ambient dreaminess of magic, mystery, inquiry and the universal.

Held together by an ether and a sense that there is something that’s bigger than all of us out there in the expanses beyond these tethered gravity fields, Stringfellow’s expletory recordings seem to drift and linger in an ambience that is one part sci-fi, another organic, and another near cosmically holy. Choral voices, again in the classical mode between the pastoral, spiritual and otherworldly near aria work of György Ligeti and Popol Vuh swell and ascend as ghostly notes and lower-case Andre Heath style piano deeply and softly tinkle or draw into focus, and sonorous low sounds pulsate or throb in the wispy airs of the cerebral.

Despite the ambience and leitmotif of nature, the walks through the meadows and environmental field recorded scenes, some of these tracks offer drama, a gravitas, or break into electronic passages of beats and tubular patterned, plastique padded rhythms: to these ears a touch of Luke Slater, Wagon Christ, Air Liquide and Richard H. Kirk. You could venture to suggest sophisticated, but always felt and evoking, influences of trip-hop, downtempo, minimalist techno, even club electronica. It offers some surprising directions and turns from the spells of dream-realism and amorphous gravitational anchor: you would be hard pressed to plant your feet on ground in this constantly floated mirage, despite that gravitational force that bounds you to it.

A track such as ‘The Weight Of The World’ can throw us off balance with its brilliant and subtle dissonance and giddiness; a sound collage of layers, both found and collected and made anew, includes a kind of Revolution No.9 style Stravinsky type tune-up heightened fit of excitable and swirling orchestra, Don Cherry and Booker Little style cornet trumpet, a trudge through the grass, piques of reality and the beats of Howie B. I’m hearing hints of Fran & Flora, Xqui, Greg Nieuwsma & Antonello Perfetto and Alison Cotton converging with Bernard Szajner and Richard H. Kirk on an album of differing but congruous moods. For this feels like one long conceptual piece: Sure, each track begins as it also finishes as a separate vision, but without much effort they could more or less run seamlessly together with no pauses or interruptions into one ambitious movement of essence and reverberated fantasy.

You’ll be hard pressed to find a better, more complete vision in this field of musical, sonic and field recorded experiment this year: I say experiment, but this is a most lovely if sometimes mysterious and alien work of art to lose yourself in for an hour.

Jeff Bird ‘Ordo Virtutum: Jeff Bird Plays Hildegard von Bingen, Vol 2’

(Six Degrees Records) Released last month

Both outside itself with a certain gravity and majesty and sense of presence that isn’t wholly religious and divine, and yet very personal and sensitive to its creator, Jeff Bird’s second volume of harmonica, organ pump and Fron initiated compositions transposes the liturgies of the venerated historical European polymath figure of Hildegard of Bingen, taking her famous Order of Virtues play and transporting its glorious Benedictine stained-glass chorales and an essence of the anointed versant landscapes of Medieval Europe, to a vision of both of America’s Old West and southern borders.

Essentially, this is a further study and celebration of Bird’s love for the transcendent music of the 12th century abbess, whose talents stretched to practicing medicine, writing, philosophy and mysticism: often referred to as the “Sibyl of the Rhine”. A visionary to boot, she was also just as importantly an influential composer of “monophony”, the simple musical form typically sung by a single singer or played by a single instrumentalist – In choir, or choral form, it usually means the ensemble of voices all singing the same melody. She is indeed the patron saint of musicians and writers – although, her official canonization by the church would take over 800 years. One of her most established, noted works is a collection the Symphonia armonie celestium revelationum, an ordered liturgy of 77 sacred songs. On his previous beatified volume, Bird took another work, the O Felix anima, a piece written in poetry and music as a response to the relatively localised and obscured St. Disibod.

Ordo Virtutum – to give it its Latin name – is an allegorical morality play, or sacred music drama, composed during the construction of Hildegard’s abbey at Rupertsburg in 1151. Theme wise, a lyrical, choral and also more discordant struggle for a human soul, in a theosophy battle between the Virtues and the Devil, the story can be divided into five parts. Each part, character is represented by a singing voice or chorus; only the devil, who Hildegard says cannot produce divine harmony, is missing such a beautiful voice, his parts delivered in grunts or yells. Depending on sources, it has been suggested that the “soul” of that struggle refers to Richardis von Satde, a fellow Benedictine nun and friend, who left to become the abbess of another convent. Richardis was upset by this appointment, attempting to have it revoked. Unsuccessful, Richardis departed only to die some time shortly after – October 29th, 1151, to be precise. It has been also suggested that just before her untimely fateful death, she old her brother Bruno that she wished to return to Hildegard in an act similar to the “repentant soul” of the Ordo Virtutum.

Whatever the allusions, the allegory, it is a beautiful work; one of the first of its kind. Inspiring devotion, touched by the afflatus, Bird now transports the listener from its origins to vistas, reflections and environments that at first seem quite a distance away from that Medieval period struggle and drama. This is mostly down to the choice of instrumentation, with new arrangements created for a string orchestra, a pump organ, the harmonica and the more recently invented Fron – named after its inventor, the clockmaker and woodwork specialist Fron Reilly, this strange looking apparatus is essentially “a cylindrical instrument with a frame drum suspended in the centre of 10 strings. To play it, you have to turn a crank handle to make the instrument spin while using a bow or wand to vibrate its strings.”

A long-time foil within the Cowboy Junkies circle and multi-instrumentalist performer with an enviable list of notable artists over the decades, the founder member of the Canadian folk band Tamarack, who also scores music for TV and Film, sure has a rich CV to draw upon and channel into this project. Mastering an eclectic range of instruments, on last year’s Cottage Bell Peace Now Bird got to grips with a grand imposing pipe organ; a gift that he refurbished over time. I said at the time, when reviewing this highly recommended work, that in his hands the “pumped waves and layers emote spatial lenses, dusted beams of light, the concertinaed, ripples and spells of near uninterrupted cycles of abstract soul searching and peaceful inquiry.” And now back again, entwinned at times with the hinge-motion, country pining, mirage-invoked and concertinaed harmonica, this organ lays down breaths and sonorous deeply moving empyreal and elegiac beds and melodic directions to folkloric warriors, spiritual transcendence, redemption and the solace.

This is music that is both relenting and deeply moving; a sensitive but powerful score that twins alternative Western scores and music with the pastoral, classical and blessed. I’m picturing Bob Dylan Portraits, old Missouri, the southern borders of America in the 19th century, the work of Daniel Vickers, Laaraji and Bruce Langhorne; the lone bugle caller at a fort, a Colliery band, a Lutheran Popol Vuh. There’s just a passing evocation of the Cantonese on the spindled and string pulled ‘The Old Serpent Has Been Bound’; Bird creates a sort of shivered, scaly-like mythical dragon description from his chosen instrument that conjures up esoteric and supernatural illusions.

Dreamily merging various worlds into an hallucination of church parable and the more personal, Bird has pitched this album perfectly between swelling gravitas and the ambient and calming. Hildegard’s original is given a new impetus, a new direction, a living breathing embodiment of Bird’s Western visions and beyond. In one word: superb. And one of my favourite immersive experiences in a long time. The Devil it turns out, doesn’t always have the best tunes.

Dope Purple ‘Children In The Darkness’

(Riot Season Records) 20th June 2025

Seeing the light two years on from its inception in March of 2023, the midnight hour recording sessions that make up this mystical, supernatural album conjure up temple lurked spirits, an expressive cry from the shrouds, and monastic Shinto apparitions. All of which is consumed and enveloped within an acid-psych space-rock and fee-jazz rock out of the contorted, squeezed and wailed.

The Taiwanese group with feelers that extend out towards much of Southeast Asia, were joined on that fateful night by the Malaysian saxophonist Yong Yandsen and the British, but Singapore-based, drummer Darren Moore, and an audience of head music acolytes.

Just the sort of thing you’d expect from the mighty Riot Season camp, the trio of tracks that make up Children In The Darkness sound like Nic Turner going full welly on the saxophone whilst his Hawkwind band mates whip up a cosmic cacophony. But there’s far more to process than just that glib one-liner description, as the group also bleat, go wild, score, screech, peck, spin and whip up evocations of Bill Dixon, the ZD Grafters, Last Exit, Acid Mothers Temple, Ghost, Anthony Braxton and John Sinclair’s Beatnik Youth recordings with Youth.

Whilst unbound to a particular theme or a concept as such, the title was invoked by the atmosphere and mood of that session, recorded at Revolver in the Taiwan capital of Taipei City. And though it summons forth certain allusions to the chthonian, to the esoteric, and to the metaphorical, I can’t help feeling there is something in it about the uncertain, dreaded shadow of China and the limbo of the geopolitical events that could result in an invasion of that sovereign island nation: A new young generation used to freedoms and liberty on the precipice of a tyrannical struggle. For it is certainly near a horror show in places, summoning up the old spirits. But this album seems like a pained whelp from the shadows and an interstellar oscillation, ariel bending motherboard of escapist space projections that go both hard and more sensitively, with plenty of incipient starry passages, the odd near tender, mournful moment and some parts which seem more languid and emotionally drawn.

A great trip from a dope name play on the progenitors of dark and harrowed heavy meta(l), the Purple host go full on cosmic-occult.

Tigray Tears ‘The World Stood By’

13th June 2025

As attention spans seem to contract and the 24-hour newsfeed cycle is forced to update and move on every nanosecond in the battle to retain minds and lock in followers for monetary gain and validation, or to offer up a hit of dopamine, many geopolitical events – once seen as cataclysmic and about to push the world into climate crisis or war – seem to be quickly forgotten about. Usurped for the most part and replaced by the next teetering-into-the-abyss flashpoint, the next outrage. And so, as I’ve said before about the Rohingya genocide in a previous review, do you remember the humanitarian crisis, the large-scale deaths in the conflict between Tigray and Ethiopia? Of course you don’t. That’s old news. Slipped from the public gaze. We’ve had the aftereffects of COVID to contend with, the cost-of-living crisis and high inflation, Russia’s barbaric invasion of Ukraine, the continuing incursions of Islamic terrorism in Africa, and now, since the horrific vile attacks on Israel on October 7th by Hamas, another ongoing escalating conflict in the Middle East. Chuck in Trump’s return to power, and the ensuing appeasement of both Putin and China (will they, won’t they, soon invade Taiwan), the huge mess that is the Tariff wars, civil unrest and disillusionment, and what could be a full scale war between India and Pakistan and there just doesn’t seem to be enough room or bandwidth to take it all in, let alone worry and press for solutions.

Once again, the producer extraordinaire, writer and musician Ian Brennan is on hand to wake us from our stupor and ignorance; this time setting up his in-situ style recording equipment to record the pleaded, sorrowful, longed and outraged but just as magical and astonishing voices and music of exiled Tigray living in the Ethiopian capital of Addis Ababa and the Amhara region; forced to leave their disputed home in what many describe as a civil war, others a conflict over autonomy and rights, and others still, a battle between ethnic groups for dominance in the region.

To be honest, it’s far beyond my own knowledge and scope of specialism, the conflict fought in the Tigray region (the most northern state within the borders of Ethiopia) is convoluted and has a long history stretching back generations. But to be brief, this two-year conflict pitted forces allied to the Ethiopian federal government and Eritrea against the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF). The TPLF had previously been a dominant force politically in Ethiopia before conflict with its neighbours, unrest within the country, and disputes over leadership spilled out into horrific violence. But during this particular and most recent chapter, between the 3 November 2020and 3 November 2022, it is estimated that two million people were displaced from the region, and 600,000 killed. Tigray was itself left in ruins; its capital turned over to the federal government. Reports began to emerge in the aftermath of ethnic cleansing and war crimes. And the situation is no more stable now, a few years along, with conflict once more looming with Eritrea.

Loosened and set free from the archetypal studio, Ian’s ad hoc and haphazard mobile stages have included the inside of a Malawi prison, disputed regions of the Mali deserts, and the front porches and back rooms of Southeast Asia: one of which was on the direct flight path of the local airport. And yet that is only a tiny amount of the forty plus releases Brennan has recorded over the last two decades.

As if being a renowned producer of serious repute wasn’t already enough, he could also be considered a quality author; so far publishing four digestible tomes on a range of music topics and regularly contributing to a myriad of publications. He’s turn of phrase and candid nature brings music, the relationships, and journeys to vivid life, whilst never blanching from describing the harrowing, disturbing and traumatic realities of the geo-political situations, the violence – each release features a brilliant vivid travelogue written by Brennan to set the mood.

As a violence prevention expert and advocate, Brennan’s recordings can be said to act as both a testament and a healing process. It has taken him and his partner, foil on many of these recording projects, the Italian-Rwandan photographer, author and filmmaker Marilena Umuhoza Delli, who documents each trip, to some of the most dangerous places in the world; many of which have had little or no real coverage by the wider media.

The partnership now turns attention to the injustice and plight of the Tigray, perhaps one of the most forgotten or ignored groups in recent times – although the Rohingya of Myanmar (Brennan released a project on this very topic last year), the Uyghurs of China, and various other ethnic groups that have faced or are facing similar acts of violence, of ethnic cleansing and displacement could argue their cases just as strongly. The exiled are given an opportunity to reach the audience that so ignored them, with various voices conveying their fears and hopes, but also asking, pleading why it was allowed to happen. As Brennan says in the intro, “The majority sang plaintively and with unerring directness. As so often proved the rule, the person with the worst attitude proved the best singer. They were unburdened by any seeming eagerness to please.” But in saying that, there’s not really one example of the angered, the riled rand enraged; seldom any political redress but instead, either humbled and soulfully yearned expressions of the reconciliatory, some with heartache, and others, with voices that carry and echo. You only have to read those titles to gauge the mood here: ‘Wishing For Peaceful Time To Return’, ‘I Want My Mother To Be Happy And At Peace’, ‘Please Speak Kindly To Avoid Arguments (People Should Live In Love)’. All of which, staying connected to their roots and homeland, are sung in the Tigrinya language: from the soul.

Brennan doesn’t normally go in for editing much, nor does he usually add filters or effects, but this time around he seems to have congruously reverberated and played with some of the original organic recordings to give them an experimental and contemporary feel: something that transcends the location, heading towards the otherworldly, cosmic and the atmospheric. None more so than track ‘No Matter Where I Am, I Miss Tigray’, which fades into a gathering of various interlayered high and lower pitched vocals and a near trill but ends up enveloping the participants into some cosmic wind tunnel. And vocal on ‘My Heart Pleads For Your Forgiveness’ is undulated by shooting ray beams and quasi-spacey vibes.

Most of these singers are accompanied by the rustically struck, brushed and rhythmically stringy Krar, a five or six-stringed lyre tuned to the pentatonic scale (that’s five notes per octave) that was used to “adulate feminine beauty, create sexual arousal, and eulogize carnal love”. The Derg military junta that ruled the region and Eritrea between the mid 1970s and 1980s banned its use: going as far as to imprison those who played this popular instrument. The Wikipedia entry states that the krar had been “associated with brigands, outlaws, and Wata or Azmari wanderers. Wanderers played the krar to solicit food, and outlaws played it to sing an Amhara war song called Fano.” Brennan calls it the “sonic core for the [Tigray] culture”.

Sound wise, what is interesting and revelatory is the connections, the similarities and evocations between this region of East Africa and that of Southeast Asia (I’m thinking Cambodia and Vietnam), the Tuareg and actually many of Brennan’s other recordings: a connective sense of roots music, the origins of the blues, but also the theme of processing trauma, a troubled history, the longing for a return – endurance is another.

“What is the world saying about Tigray?” Not much, especially with the crisis in next door Southern Sudan overshadowing all events in East Africa – the humanitarian tumult putting as many as nine million people at jeopardy of starvation in the tumult that has followed that country’s independence and self-determination. But in a small way, Brennan at least tries to draw attention to this plight, and I so doing, introduces many of us to unique, magical, evocative and poetic voices.

Jason van Wyk ‘Inherent’

(n5MD) 13th June 2025

From the very start the subtleties, vapours and tubular notes on the South African composer and producer’s latest album imply a certain gravitas: even in their most serene, quiet and ambient moments. For this is a work of air and wind, but substance and depth that is capable of stimulating and evoking something beyond its both melodic and textural wave forms, its hidden sources of movement and a presence that is difficult to describe.

Said to be ‘a clear evolution of its predecessor’, and striking a balance between melody and atmosphere, Jason van Wyk manages to add drama to the merest of electronic wisps and breaths, and to conjure up feelings, contemplations and yearns. Both futuristic and yet identifiable to our times, with touches of the cosmic and the cerebral, Inherent is both an album that feels connected to self-exploration and the abstract, difficult to describe senses of something greater, an undefined force of nature, of space and emotions.

What’s more, Wyk manages to artfully build some of these fields of cloud and more granular passages into the rhythmic with the introduction of sophisticated beats, throbbing and deep bass, and undulations of the tubular and magnetic. For example, ‘Inner’ evolves from its fading ambience into a trance-like amalgamation of Moroder, Sven Vath and Eastern European techno, whilst ‘Remnants’ starts off with those melodic ambient waves, stirrings of a deeper hummed bass and engine, and builds into a near club-like sound, with echoes also of Emptyset and the Bersarin Quartet. ‘Cascades’ is similar in this regard but feels more like an epic movie soundtrack.

Thrushes of wrapped electronica and static merge with gauze, melodic fluctuations and drifts and a prism of projected light sources on a beautifully produced work of mystery, exploration and reflection.

Voodoo Drummer ‘HELLaS SPELL’

Was Released on the 11th May 2025

A kind of Odyssey, weaving and transposing into something weird, otherworldly and dadaist Greek myth, tragedy, atavistic verse and the classical whilst interrupting both iconic and traditional compositions by various idiosyncratic mavericks along the way, the debut album from the Athenian duo (and contributing friends) of Chris Koutsogiannis and Stavros Pargino takes us on a both fun and evocative theatrical journey in which all roads lead back to the underworld and “hell”.

Referencing all things Greco-absurdist and mythological, the self-anointed VOODOO DRUMMER – a name that formulated after participating, we’re told, in a Benin funeral, and from his appearances on the esoteric New Orleans scene – and his cellist foil fuse lofty aspirations with a spirit of playfulness across an album of original and transmogrified material that, for the most part, relates to Hellenic culture. And yet, off the beaten track, the roots of “rebetiko” Greek music from another age, the ancient scales and poetry of that Mediterranean civilization are crossed with early 20th century America, Western and Eastern European classical music from the 19th century, the avant-garde, the stage and the counterculture.

Those Greek references include a Dionysus leitmotif. The fecund god of wine, vegetation, orchards, fruit, fertility, theatre, religious ecstasy also dealt in ritual madness and insanity, and is featured as the drunken swaying Bacchus, complete with hiccups, unsteady feet and wordless murmurs and mumbles on his namesake track. He then appears as the wicked fickle punisher of the fated mythological king, Pentheus of Thebes, in the ‘Bacchae’ tragedy. In this lamentable tale, written by the famous Euripides during his late flourishing in Macedonian court of Archelaus I, Dionysus drives poor Pentheus mad for rejecting his “cult”: rather grimly, the orgiastic frenzied women of Thebes tear him apart in the final act.

Inspired by the Ancient Greek playwright Aristophanes’ comedic play of the same title, Antiquity beckons once more as Dionysus enters stage left on ‘Aristophanes’ Frogs’; a triumvirate set of movements under one roof. With prompts, scales and falls, the liberating god, who despairing of the state of Athens’ tragedies, travels to the underworld of Hades to bring the playwright Euripides back from the dead. And so, we begin this chthonian adventure to the sounds of rattlesnake percussion, Hellenic pitter-patters, rolling drum rhythms and the plucks of 5th century BC Athens, before rowing across a splish-splashing pizzicato and majestically bowed lake (complete with a croaking frogs chorus), and a sort of Faust meets strangely quaint experimental late 60s vocal. The final movement strikes up a controlled tumult of screaming and harassed viola and “Afro-Dionysus” drums as Hades opens up and swallow’s whole. Koutsogiannis andParginosare joined on this Dionysus inspiration by Blaine L. Reininger (of Tuxedomoon note) on violin and Martyn Jacques (of the Tiger Lillies) echoing the famous line from the play.

At this point, it must be pointed out that the duo expands the ranks to include contributions from a pair of Tiger Lillies and a Malian virtuoso. Koutsogiannis toured with the former in a previous life. Here, he brings in the already mentioned Jacques to narrate the final outro on the L.A. salacious dirty-mouthed referenced figure of countercultural pulp-poet-writer Charles Bukowski – in a somewhat dry, solemn but authoritarian cadence, Jacques echoes the literary badnik’s words, “We’re here to drink beer/We’re here to kill war/To laugh and live our lives so well/that death will tremble to take us.” Tiger foil Adrian Stout takes to the quivering aria apparitional saw on the opening partnership of ‘Pink Floyd in 7/8/John Coltrane’. A Saucerful of Secrets’ ‘Set The Controls To The Heart Of The Sun’ acid-cosmic trip is somehow given a new timing signature (the original is in 7/4 timing I believe) and smoothly twinned with Coltrane’s most beloved influential work, ‘A Love Supreme’ (a more conventional 4/4 time for the most part). It starts with a recurring frame drum or military ritualistic beaten drum, has the chimed ring of tubular-like bell soundings, and features retro Library sci-fi bends and theremin like warbles before changing the rhythm to one of light shuffling jazz. Something familiar of the two separate tracks can be heard, estranged as they are. Featuring on warm and humming, almost ambled bass guitar is another cast member, Tasos Papapanos.

Coining the description of “Afro-Dionysian”, the duo’s Hellenic tastes, reinventions bond with those of West Africa on occasion; especially when the kora marvel and artist Mamadou Diabaté makes an appearance on the ragtime dadaist, boozy cup poured and rattled, shaken voodoo inebriated “Drunk Dionysus”. The Malian virtuoso plays a one octave, out-of-tune version of the African metallophone, the metal balafon (reclassed as the “Weirdofon” by the Voodoo Drummer); sounding out vibes that are one part Roy Ayers, another part bobbing chimes and tinkling tines in the style of the Modern Jazz Quartet on a field trip to Bamako.

Back to those Greek references and allusions, and the second pairing of agreeable – when the timings are changed, the originals transported to Athens – covers, ‘Erik Satie In 7/8/Milo Mou Kokkino’ pulls together the first movement of the French composer’s famous Gnossiennes pieces and a traditional melody and song from Greece. Part of the original Trois Gnossiennes (followed by a further series) that Satie composed in the later years of the 19th century, these iconic and influential piano experiments were based around what is termed a free time method (devoid of time signatures or bar divisions) that plays with form, rhythm and chorded structures. Already etymology wise – and this is very interesting as it ties in with this album’s culture themes – in use before Satie coined the term, “Gnossiennes” could be found in French literature as a reference to the ritual labyrinth dance created by Greek mythological hero Theseus to celebrate his victory over the Minotaur. It was first described in the ‘Hymn to Delos’ by Callimachus, the ancient Greek poet, scholar and librarian, who resided in 3rd century BC Alexandria. Musically those dried bones rattle once more over dainty plucks, dissipated cymbals and a courtly dance. But then the cello, punctuated by a booming beaten drum, both strikes and laments like a siren performing a gypsy folk dance.

Taken in another direction, has is the way of things by this duo, there’s a transformed version of the street poet shaman Moondog’s ‘Elf Dance’, which has a certain classical gravity, a drama, a romantic bluesy feel and touch of Eastern European Klezmer. A very interesting take on an album that transposes the familiar to different climes.

HELLaS SPELL is a Hellenic chthonian voodoo vision in which Cab Calloway, 20s jazz radio hall, the far away influences of Appalachia and New Orleans meet dada and performative conceptual theatre. An intriguing debut that deserves attention.

Warda ‘We Malo’

(WEWANTSOUNDS) 13th June 2025

Continuing to unearth and showcase recordings from those defining sirens and chanteuses of the Arabian world during a golden age, the vinyl specialists WEWANTSOUNDS once more home in on the captivating performances of the late diva Warda Mohammed Ftouk. Simply Warda as she was known to a not only North African, Middle Eastern and Levant audiences but across the world, her name became a totem, and synonymous with the fight for not only Algerian independence in one age, but also as the voice for the soundtrack to the later Arab Spring. Invited as the voice of a nation on the eve of celebrating Algeria’s fiftieth anniversary as an independent country in 2012, right in the middle of the demonstrations, Warda was meant to sing the anthemic ‘We’re Still Standing’. Sadly, it wasn’t to be, as she suffered a fatal heart attack just a couple of months before the performance. Health problems, from a liver transplant in the 1990s to heart surgery in the early 2000s, often hampered Warda’s career, more so in the decades when she returned from her hiatus in the 1960s – her husband of the time, the former FLN (Algerian National Liberation Front) militant, now army officer, Djamel Kesri forbid her to sing, and so she spent a decade concentrating on raising a family before being invited to return to singing once more, in part at the bequest of Algeria’s president Houari Boumédiène who wished her to commemorate the country’s tenth anniversary of independence from France; which she did, performing in Algiers with an Egyptian orchestra. But both sampled liberally by the hip-hop fraternity and beyond, that voice, alongside its stirring, swirled, buoyant and undulating musical accompaniment, seems even more prescient in these troubled times, with conflict and the changing tides of politics in the Middle East and further afield.

Though born in Paris, Warda’s roots were both Algerian and Lebanese. Fate however, due to the ramifications of support for the former’s independence struggle by her father, would see the family expelled from France.

Whilst only a child in the 1950s Warda made her singing debut at her father Mohammed Ftouki’s renowned cabaret and North African diaspora hotspot, La Tam-Tam (the name derives from an amalgamation of Tunisia, Algeria and Morrocco). Here she was soon discovered by Pathé-Marconi’s Ahmed Hachlaf (the artistic director, programmer and radio host charged with looking after the famous studio and label’s Arabic catalogue), who quickly managed a recording session for the nascent star. But after the club was used to hide a cache of weapons bound for the fight against the French state in Alegria (La Tam-Tam and Ftouki tied, it is said, to the FLN and the political Movement for the Triumph of Democratic Freedoms), Warda’s father was imprisoned. After his release, and now denounced by the French authorities, the family left France to live in Beirut, in the Hamra Quarter of the city. Now concentrating his efforts on both Warda and her talented brother Messaoud (a renowned percussionist and composer), Ftouki dedicated his time to training the siblings for artistic success.

A hit on the Beirut cabaret scene, in 1959 Warda’s star would rise further when she met the legendary famous Egyptian composer, screen idol, crooner and songwriter Mohammed Abdel Wahab at a casino in the Lebanon city of Aley. Wahab took the burgeoning siren under his wing, teaching her classical techniques and writing for her: famously adapting the poet Ahmed Shawqi’s ‘Bi-Omri Kullo Habbitak’ “qasida” (an ancient Arabic word for poetry, often translated as “ode”). A leading light, able to rub shoulders with the great and impressive, Wahab’s name could open doors across the board, especially with the Arab leadership of the time, including Gamel Abdel Nasser. The infamous Egyptian leader suggested that Warda be cast in a pan-Arabian opera and perform Wahab’s ‘Al Watan Al Akbar’ song. She was duly signed by Helmy Rafla, the Egyptian director of musicals. A career on stage and the silver-screen followed, with Warda starring in both the Almaz We Abdo El-Hamouly and Amirat al-Arab films.

However, in a new decade, the 1960s, she married Kesriand took a forced break from her singing. Warda would divorce Kesri on the cusp of the 1970s (rather amicably we’re told), once more making a move and taking up permanent residence in Egypt, where she resumed her career once more. During this next chapter, she would remarry the Egyptian composer of note Baligh Hamdi, who went on to compose Warda’s most famous song. Working now with many of the country’s top composers, Warda would however fall foul of Egypt’s leader Anwar Sadat, who banned her from performing after she praised Arab rival leader, and dictatorial Libyan tyrant Muammar Gaddafi in the song ‘Inkan el-Ghala Yenzad’. Egypt’s First Lady and fan, Jehan Sadat, would thankfully soon lift this ban.

Warda’s career hit its peak during that decade, seeing her make a return to France for a famous recital at the iconic Olympia. And during the 80s and 90s, despite numerous health problems, some near fatal, Warda would cement her reputation as one of the Arabian world’s most beloved, respected divas.

This latest release from the vinyl revivalists both honours and goes some way to capturing the star at her peak during the 1970s. Partnering with her husband Hamdi, she created a series of albums filled, as the notes describes, ‘with lengthy, hypnotic compositions that showcased her commanding voice”. WEWANTSOUNDS and their partners have chosen to revive one such album, We Malo (or “So What”); a mesmerising, dramatic and near theatrical live recording from 1975. Backed by an Egyptian orchestra of signature rousing, stirred and attentive strings and the fluted, and by buoyant, dipped hand drums, an organ of some kind and the contemporary addition of a both trebly and bassy electric guitar, Warda, unsurpassed, holds the audience’s attention with a superb performance that runs through the emotions.

As story, declaration, or ode, Warda is as strong as she is venerable, reciting and playing with an appreciative audience, who clap, shout out, whistle and join in like for passages of call-response. She can be as coy and near flirtatious as she can be emotionally rousing and commanding. From plaintive heartache to vocally dancing over the attuned orchestral accompaniment, the nightclub atmospheric performance shimmies, swirls and lifts to a signature Egyptian matinee score. Warda is on a musical or film set, as she flows the contours of the sand dunes and embodies the spirited pull of an exotic land.

Repeating certain parts, musically and vocally, the whole five sectioned alum is essentially one long piece with pauses and sections when the music is wound down ready to strike up again for the next part. From the opulent regal and cabaret stage instrumentation and exotic belly-dancing-like trinkets shaking to the prominent in the mix sliding and plucked guitar notes of the later parts, you can easily hear why so many samplers, crate diggers form the hip-hop community have picked up on Warda’s back catalogue: you’ve probably never even realised that you’ve heard her reverent, romantic pleads and intonation sustained undulations before, cut-up and repurposed for a new generation.

Both very much of her age and yet timeless, stretching back to the atavistic soul of North Africa, but just as relevant for the age of cinema, and propelled forward, the voice of struggle, of self-determination in a tumultuous upended Arabian world, Warda’s voice cuts right through to hit you both hard and softly. But this album is like a familiar friend, welcomed and applauded back into the spotlight; a both fun and emotionally charged drama of falls, sweeps, swoons, the held and powerful. What a talent.

An essential purchase for those with a penchant for revered sirens of the Arabian world, We Malo is a gift of an album. Dominic Valvona

If you’ve enjoyed this selection, the writing, or been led down a rabbit hole into new musical terrains of aural pleasure, and if you can, then you can now show your appreciation by keeping the Monolith Cocktail afloat by donating via Ko-Fi.

For the last 15 years both me and the MC team have featured and supported music, musicians and labels we love across genres from around the world: ones that we think you’ll want to know about. No content on the site is paid for or sponsored, and we only feature artists we have genuine respect for /love or interest in. If you enjoy our reviews (and we often write long, thoughtful ones), found a new artist you admire or if we have featured you or artists you represent and would like to say thanks or show support, than you can now buy us a coffee or donate via https://ko-fi.com/monolithcocktail

Our Daily Bread 615: Sahra Halgan ‘Hiddo Dhawr’

March 26, 2024

ALBUM REVIEW: DOMINIC VALVONA

Sahra Halgan ‘Hiddo Dhawr’

(Danaya) 29th March 2024

Few artists from the disputed region of Somaliland could qualify better than the singer, freedom fighter and activist Shara Halgan to represent their country’s musical legacy. As an unofficial cultural ambassador and symbol for female empowerment Halgan’s journey is an inspiring one: Forced out of her homeland during a destructive civil war – in which she played a part in nursing and “comforting” fighters from Somaliland’s secession movement, sometimes alleviating suffering through song –, Halgan had to flee abroad to “survive” hardships and dislocation in France, but eventually, a decade after the overthrow of Siad Barre’s ruling military junta, returned home to motivate and promote proud in Somaliland’s cultural heritage.

It was during her time in France, removed from her roots and homesick, that Halgan would meet the musicians that went on to form her studio and touring band: step forward percussionist and founder of the French-Malian group BKO Quintet, Aymeric Krol, and the guitarist and member of the Swiss ensemble Orchestre Tout Puissant Marcel Duchamp and L’etrangleuse, Maël Salètes. Both appear on the latest, and third Halgan album, alongside newest recruit Régis Monte, who adds “vintage organ” and “proto-electronic embellishments” to the heady and fuzzed mix.

Before we go any further, a little insight, context is called for, as Halgan’s themes, messages are wrapped up in the history, turmoil and ambitions of this disputed region on the Horn of Africa. Firstly, Somaliland is an independent state within the greater scope of a troubled geography, neighbour’s to Somalia, Djibouti and Ethiopia. Going back to the 7th century, this land’s tribes were swept up in the great Islamic conversion, but by the 14th century, as power shifted between states and kingdoms, they came under the suzerainty of the, then, Christian Ethiopian Empire. Islam would always remain integral, through not only its teachings but poetry too. Fast-forward to the late 1800s and the arrival of the British, who established the troublesome protectorate of British Somaliland; joined in the region by the ambitions of Italy. Although this forced state lasted up until independence in 1960, there would be a number of rebellions and breakaway movements – most notably, the Dervish State revolt set up by Sayyid Mohamed and the poet Salihiyya Sufi in the late 1800s and early 1900s; a convoluted story that needs far more space and depth than I can offer, but that’s goals were to essentially reestablish the Sufi system of governance and independence; this period would eventually lead to the establishment of the state of Somalia, but also war amongst the colonial powers and neighbouring Ethiopia.

When independence did arrive in 1960, there was a brief blossoming for Somaliland, the “de jure” unrecognized breakaway part of Somali. Existing for a mere five years as a “sovereign entity”, it was gobbled up into the greater Republic of Somalia. But it is said that this fleeting state was economically and artistically fully independent and burgeoning before “internal tensions and violent repression” took its toll; leading later to the already mentioned civil war that kicked off in 1981, finally ending with the overthrow of Siad Barre and his military junta in 1991. Somaliland currently remains a fully functioning, near stable, state, one of the safest in the region despite all the turmoil and civil war over the border in Ethiopia, the turmoil of Somali and greater dangers of Islamic insurgencies, and now the extended crisis taking hold in the Middle East.

Since her return to the homeland in 2005, Halgan has helped nourish and cultivate a female-led scene by setting up the capital’s first music venue in the more tranquil surroundings of downtown Hargeisa – the once atavistic trading hub and watering hole for the local tribes, growing into a successful city over time, it’s also the de facto governing capital of Somaliland. The name of which, Hiddo Dhawr (which the PR notes translate literally as “promote culture”), now lends its name to this new album of eclectic fusions and Somaliland traditions. A hybrid if you will, Halgan and her group really open up to an abundance of influences and atmospheres whilst retaining the unmistakable sound of the environment and legacy; from the wild trills to griot storytelling poetics and general effortless sounding buoyancy and contoured sand dune rhythms and feel.

But first, the lead single and opening track, ‘Sharaf’ bounds in on a semi-garage, semi-Glam-rock and semi-swamp-boogie backbeat. A “love song and hymn to the importance of human dignity”, this electrified, fuzzy scuzz guitar licked desert rocker has both afflatus and loving intentions; Halgan’s voice nothing but lifting and softly commanding. By the second track, ‘Laga’, a “tender love song” is transported to both Egypt and Bamako in Mali, via the organ prods and radiant suffused keys of both Question Mark and the Mysterians and Hailu Mergia.

Melodious examples of the “modern style” of Qaraami can be found transformed on bluesy and wrangled dirty guitar, trinket jingling, and rocking accompanied title-track, and the soul-beat, hand-clapped giddy ‘Diiyoohidii’. Whilst that age-old form’s subject matter is love, Halgan replaces it with a love for her people, the culture and fertile land itself. Both are beautifully, emotionally conveyed, with a semblance of both pop and rock ‘n’ roll – I’m hearing both The Artic Monkeys and Dirt Music with a touch of Les Amazones d’Afrique.

Some songs change vocally between the lyrical and the narrated, or the spoken. ‘Lilalaw’ features the later, an address to a near two-tone beat fusion of the spacy desert trance, twirled and trundled African percussion and swamp blues pedals fuzz. The finale, ‘Dareen’, is almost entirely stripped back to allow a longing unimpeded curtain call from Halgan; only the suffused subtle keys of a Muscle Shoals-like organ across the swept vistas is needed. Talking of atmospheres, the Malian blues and dried bones and beads shaken ‘Hooyalay’ features cosmic desolation and misty mysterious vibes and winds, making it the album’s most experimental song.

Enriched soul music with a edge and buzz, Halgan and her troupe strike a balance between the heartfelt and empowered on electrifying album; that focal voice sounding so fresh and young yet wise and experienced, able to encapsulate a whole culture whilst moving forward.

Tickling Our Fancy 069: Minyeshu, Dr. Chan, Brace! Brace!, Grand Blue Heron, Don Fiorino and Andy Haas…

October 9, 2018

Dominic Valvona’s new music reviews roundup

Another fine assortment of eclectic album reviews from me this month, with new releases from Papernut Cambridge, Sad Man, Grand Blue Heron, Don Fiorino and Andy Haas, Junkboy, Dr. Chan, Minyeshu, Earthling Society and Brace! Brace!

In brief there’s the saga of belonging epic new LP from the Ethiopian songstress Minyeshu, Daa Dee, a second volume of Mellotron-inspired library music from Papernut Cambridge, the latest Benelux skulking Gothic rock album from Grand Blue Heron, another maverick electronic album of challenging experimentation from Andrew Spackman, under his most recent incarnation as the Sad Man, a primal avant-garde jazz cry from the heart of Trump’s America from Don Fiorino and Andy Haas, the rage and maelstrom transduced through their latest improvised project together, American Nocturne; and a bucolic taster, and Music Mind compilation fundraiser track, from the upcoming new LP from the beachcomber psychedelic folk duo Junkboy.

I’ve also lined up the final album from the Krautrock, psychedelic space rocking Earthling Society, who sign off with an imaginary soundtrack to the cult Shaw Brothers Studio schlockier The Boxer’s Omen, plus two most brilliant albums from the French music scene, the first a shambling skater slacker punk meets garage petulant teenage angst treat from Dr. Chan, The Squier, and the second, the debut fuzzy colourful indie-pop album from the Parisian outfit Brace! Brace!

Minyeshu ‘Daa Dee’ (ARC Music) 26th October 2018

From the tentative first steps of childhood to the sagacious reflections of middle age, the sublime Ethiopian songstress Minyeshu Kifle Tedla soothingly, yearningly and diaphanously articulates the intergenerational longings and needs of belonging on her latest epic LP, Daa Dee. The sound of reassurance that Ethiopian parents coo to accompany their child’s baby steps, the title of Minyeshu’s album reflects her own, more uncertain, childhood. The celebrated singer was herself adopted; though far from held back or treated with prejudice, moving to the central hub of Addis Ababa at the age of seventeen, Minyeshu found fame and recognition after joining the distinguished National Theatre.

In a country that has borne the scars of both famine and war, Ethiopia has remained a fractious state. No wonder many of its people have joined a modern era diaspora. Though glimmers of hope remain, and in spite of these geopolitical problems and the fighting, the music and art scenes have continued to blossom. Minyeshu left in 1996, but not before discovering such acolytes as the doyen of the country’s famous Ethio-Jazz scene, Mulatu Astatke, the choreographer Tadesse Worku and singers Mahmoud Ahmed, Tilahun Gessesse and Bizunesh Bekele; all of whom she learnt from. First moving to Belgium and then later to the Netherlands, the burgeoning star of the Ethiopian People To People music and dance production has after decades of coming to terms with her departure finally found a home: a self-realization that home wasn’t a geographical location after all but wherever she felt most comfortable and belonged: “Home is me!”

The beautifully stirring ‘Yetal (Where Is It?)’ for example is both a winding saga, with the lifted gravitas of swelling and sharply accented strings, and acceptance of settling into that new European home.

Evoking that sense of belonging and the theme of roots, but also paying a tribute and lament to the sisterhood, Minyeshu conveys with a sauntering but sorrowful jazzy blues vibe the overladen daily trudge of collecting wood on ‘Enchet Lekema’; a hardship borne by the women of many outlier Ethiopian communities. Though it can be read as a much wider metaphor. The blues, in this case, the Ethiopian version of it (perhaps one of its original sources) that you find on ‘Tizita’ (which translates as ‘longing’ or ‘nostalgia’), has never sounded so lilting and divine; Minyeshu’s cantabile, charismatic soul harmonies, trills and near contralto accenting the lamentable themes.

There is celebration and joy too; new found views on life and a revived tribute to her birthplace feature on the opulently French-Arabian romance ‘Hailo Gaja (Let’s Dance)’, and musically meditating, the panoramic dreamy ‘Yachi Elet (That Moment)’ is a blissed and blessed encapsulation of memories and place – the album’s most traversing communion, with its sweet harmonies, bird-like flighty flutes and waning saxophone.

Not only merging geography but musical styles too, the Daa Dee LP effortlessly weaves jazz (both Western and Ethiopian) R&B, pop, dub, the theatrical, and on the cantering to lolloping skippy ‘Anteneh (It Is You?)’, reggae. Piano, strings and brass mix with the Ethiopian wooden washint flute and masenqo bowed lute to create an exotic but familiar pan-global sound. Minyeshu produces a heartwarming, sometimes giddy swirling, testament that is exciting, diverse and above all else, dynamic. Her voice is flawless, channeling our various journeys and travails but always placing a special connection to those Ethiopian roots.

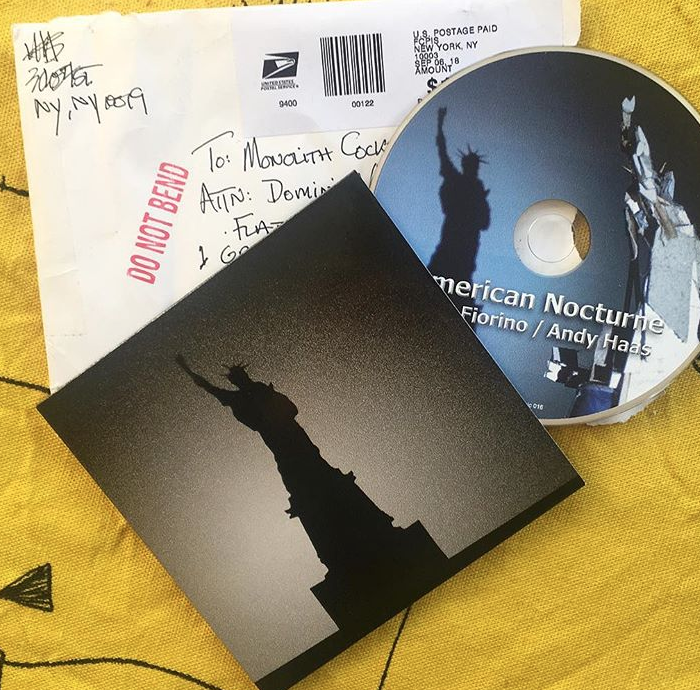

Don Fiorino and Andy Haas ‘American Nocturne’ (Resonantmusic) 16th September 2018

Amorphous unsettling augers and outright nightmares permeate the evocations of the American Nocturne visionaries Don Fiorino and Andy Haas on their latest album together. Alluded, as the title suggests, by the nocturne definition ‘a musical composition inspired by the night’, the darkest hour(s) in this case can’t help but build a plaintive warning about the political divisive administration of Trump’s America: Nicola Plana’s sepia adumbrated depiction of Liberty on the album’s cover pretty much reinforces the grimness and casting shadows of fear.

Musically strung-out, feeding off each other’s worries, protestations and confusion, Fiorino and Haas construct a lamentable cry and tumult of anger from their improvised synthesis of multi-layered abstractions.

Providence wise, Haas, who actually sent me this album after seeing my review of a U.S. Girls gig from earlier in the year (he was kind enough to note my brief mention of his Plastic Ono Band meets exile-in-America period Bowie saxophone playing on the tour; Haas being a member of Meg Remy’s touring band after playing on her recent LP, In A Poem Unlimited), once more stirs up a suitably pining, troubled saxophone led atmosphere; cast somewhere between Jon Hassell and Eno’s Possible Musics traverses, serialism jazz and the avant-garde. The Toronto native, originally during the 70s and early 80s a band member of the successful Canadian New wave export Martha And The Muffins, is an experimental journeyman. Having moved to New York for a period in the mid 80s to collaborate with a string of diverse underground artists (John Zorn, Marc Ribot, Thurston Moore and God Is My Co-Pilot) he’s made excursions back across the border; in recent times joining up with the Toronto supergroup, which features a lion’s share of the city’s most interesting artists and of course much of the backing group that now supports Meg Remy’s U.S. Girls, the Cosmic Range (who’s debut LP New Latitudes made our albums of the year feature in 2016). He’s also been working with that collective’s founder, Matt ‘Doc’ Dunn, on a new duo project named KIM (the fruits of which will be released later this year). But not only a collaborator, Haas has also recorded a stack of albums for the Resonantmusic imprint over the years (15 in total), the first of which, from 2005, included his American Nocturne foil, Fiorino. An artist with a penchant for stringed instruments (guitar, glissenter, lap steel, banjo, lotar, mandolin), Fiorino is equally as experimental; the painter musician imbued by blues, rock, psychedelic, country, jazz, Indian and Middle Eastern music has also played in and with a myriad of suitably eclectic musicians and projects (Radio I Ching, Hanuman Sextet, Adventures In Bluesland and Ronnie Wheeler’s Blues).

Recorded live with no overdubs, the adroit duo is brought together in a union of discordant opprobrious and visceral suffrage. Haas’ signature pained hoots, snozzled snuffles and more suffused saxophone lines drift at their most lamentable and blow hard at their most venerable and despondent over and around the spindly bended, quivery warbled and weird guitar phrases of Fiorino. Setting both esoteric and mysterious atmospheres, Haas is also in charge of the manic, often reversed or inverted, and usually erratic drum machine and bit-crushing warped electronic effects. Any hint of rhythm or a lull in proceedings, and it’s snuffed out by an often primal and distressed breakdown of some kind.

Skulking through some interesting soundscapes and fusions, tracks such as the opening ‘Waning Empire Blues’ conjures up a Southern American States gloom (where the Mason-Dixon line meets the dark ambient interior of New York) via a submerged vision of India. It also sounds, in part, like an imaginary partnership between Hassell and Ry Cooder. ‘Days Of The Jackals’ has a sort of Spanish Texas merges with Byzantium illusion and ‘New Orphans’ transduces the Aphex Twin into a shapeless, spiraling cacophony of pain.

With hints of the industrial, tubular metallic, blues, country, electro and Far East to be found, American Nocturne is essentially a deconstructive jazz album. Further out than most, even for a genre used to such heavy abstract experimentation, this cry from the bleeding heart of Trumpism opposition is as musically traumatic as it is complex and creatively descriptive. Fiorino and Haas envision a harrowing soundtrack fit for the looming miasma of our times.

Papernut Cambridge ‘Mellotron Phase: Volume 2’ (Ravenwood Music/Gare du Nord) 5th October 2018

A one-man cottage industry (a impressively prolific one at that) Ian Button’s Eurostar connection inspired label seems to pop up in every other roundup of mine. The unofficial houseband/supergroup and Button pet project Papernut Cambridge, the ranks of which often swell or contract to accommodate an ever-growing label roster of artists, is once again widening its nostalgic pop and psychedelic tastes.

Following on from Button’s debut leap into halcyon cult and kitsch library music, Mellotron Phase: Volume 1 is another suite of similar soft melodic compositions, built around the hazy and dreamy polyphonic loops of the iconic keyboard: An instrument used to radiant, often woozy, affect on countless psych and progressive records. That first volume was a blissful, float-y visage of quasi-David Axelrod psychedelic litany, pop-sike, quaint 60s romances and a mellotron moods version of Claude Denjean cult lounge Moog covers.

This time around the basis for each instrumental vision is the rhythm accompaniments from Mattel’s disc-based Ontigan home-entertainment instrument. These early examples of instrumental loops and musical breaks were set out across the instrument’s keys so that chord sequences and variations can be used to construct an arrangement. Mellowed and toned-down in comparison to the first volume, though still featuring drum breaks, percussion, bass and on the Bacharach-composes-a-screwball-tribute-to-French-Western-pulp-fiction (Paris, Texas to Paris, France) ‘A Cowboy In Montmartre’, an accordion. If the French Wild West grabs you then there’s plenty of other weird and wonderful mélanges to be found on this whimsically romantic, sometimes comically vaudeville, and often-yearning fondly nostalgic album. The swirling cascade of soft focus tremolo vibrations of the stuttered ‘Cha-Cha-Charlie’ sounds like Blue Gene Tyranny catching a flight on George Harrison’s Magical Mystery Tour. The Sputnik space harp pastiche of ‘Cygnus Probe’ is equally as Gerry Anderson as it is Philippe Guerre, and ‘Boss Club’ reimagines Trojan Records transduced through lounge music. Kooky Bavarian Oompah Bands at an acid-tripping Technicolor circus add to the mirage-like mellotron kaleidoscope on ‘Sergeant Major Mushrooms’, Len Deighton’s quintessentially English clandestine spy everyman, as scored by John Barry, cameos on the clavinet spindly and The Kramford Look-esque ‘Parker’s Last Case’, and Amen Corner wear their soft soul shufflers on the Tamala backbeat ‘Soul Brogues’.

A curious love letter to the forgotten (though a host of champions, from individuals to labels, have revalued and showcased their work) composers and mavericks behind some of the best and most odd library music, Mellotron Phase will in time become a cult album itself. As quirky as it is serenading, alternative recalled obscure soundtracks that vaguely recall Jean-Pierre Decerf, Jimmy Harris, Stereolab, Jean-Claude Vannier and even Roy Budd are given a fond awakening by Button and his dusted-off mellotron muse.

Sad Man ‘ROM-COM’ October 2018

Haphazardly prolific, Andrew Spackman, under his most recent of alter egos, the Sad Man, has released an album/collection of giddy, erratic, in a state of conceptual agitation electronica every few months since the beginning of 2017. Many of which have featured in one form or another in this column.

The latest and possibly most restive of all his (if you can call it that) albums is the spasmodic computer love transmogrification ROM-COM. An almost seamless record, each track bleeding into, or mind melding with the next, the constantly changing if less ennui jumpy compositions are smoother and mindful this time around. This doesn’t mean it’s any less kooky, leaping from one effect to the next, or, suddenly scrabbling off in different directions following various nodes and interplays, leaving the original source and prompts behind. But I detect a more even, and daresay, sophisticated method to the usual skittish hyperactivity.

Showing that penchant for exploration tracks such as the tribal cosmic synwave ‘Play In The Sky’ fluctuate between the Twilight Zone and tetchy, tentacle slithery techno; whilst the shifting bit-crush cybernetic ‘Hat’ sounds like a transplanted to late 80s Detroit Art Of Noise one minute, the next, like a isotope chilled thriller soundtrack. Reverberating piano rays, staggered against abrasive drumbeats await the listener on the sadly melodic ‘King Of ‘. That is until a drilling drum break barrels in and gets jammed, turning the track into a jarring cylindrical headbanger. ‘Coat’ whip-cracks to a primitive homemade drum machine snare as it, lo fi style, dances along to a three-way of Harmonia, The Normal and Populare Mechanik, and the brilliantly entitled ‘Wasp Meat’ places Kraftwerk in Iain Banks Factory.

Almost uniquely in his own little orbit of maverick bastardize electronic experimentation, Spackman, who builds many of his own bizarre contraptions and instruments, strangulates, pushes and deconstructs techno, the Kosmische, Trip-Hop and various other branches of the genre to build back up a conceptually strange and bewildering new sonic shake-up of the electronic music landscape.

Grand Blue Heron ‘Come Again’ (Jezus Factory) October 19th 2018

Grand Blue Heron, or GBH as it were, do some serious grievous harm to the post-punk and alt-rock genres on their latest abrasive heavy-hitter, Come Again. Partial to the Gothic, the Benelux quartet prowl in the miasma; skulking under a repressed gauze and creeping fog of doom as they trudge across a esoteric landscape of STDs, metaphorical crimes of the heart and rejection.

Born out of the embers of the band Hitch, band mates Paul Lamont (who also served time with the experimental Belgium group and Jezus Factory label mates, A Clean Kitchen Is A Happy Kitchen) and Oliver Wyckhuyse formed GBH in 2015 as a vehicle for songs written by Lamont. Straight out of the blocks on their thrashing debut Hatch, they’ve hewn a signature sound that has proven difficult to pin down.

Both boldly loud with smashing drums and gritty distorted guitars, yet melodic and nuanced, they sound like The Black Angels and Bauhaus working over noir rock on the vortex that is ‘Wwyds’, a grunge-y Belgium version of John Lyndon backed by The Pixies on the controlled maelstrom title-track, and Metallica on the country-twanging, pendulous skull-banger ‘Head’. They also sail close to The Killing Joke, Sisters Of Mercy (especially on the decadent wastrel Gothic ‘The Cult’), Archers Of Loaf and, even, The Foo Fighters. They rollick in fits of rage and despondency, beating into shape all these various inspirations, yet they come out on top with their own sound in the end.

Playing live alongside some pretty decent bands of late (White Denim, Elefant, The Cult Of Dom Keller) the GBH continue to grow with confidence; producing a solid heavy rock and punk album that reinforces the justified, low-level as it might be, hype of the Belgium, and by extension, Flanders scene.

Dr. Chan ‘Squier’ (Stolen Body Records) October 12th 2018

Keeping up the petulant garage-punk-skate-slacker discourse of their obstinate debut, the French group with just a little more control and panache once more hang loose and play fast with their spikey influences on the second LP Squier.

Hanging out with a disgruntled shrug in a 1980s visage of L.A. central back lots, skating autumn time drained pools in a nocturnal motel setting, Dr. Chan crow about the transition from adolescence to infantile adulthood. Hardly more than teenagers themselves, the band seem obsessed with their own informative years of slackerdom; despondently ripping into the status of outsiders the lead singer sulkingly declares himself as “Just a young messy loser” on the opening boom bap garage turn space punk spiraling ‘Wicked & Wasted’, and a “Teenage motherfucker” on the funhouse skater-punk meets Thee Headcoats ‘Empty Pockets’.

The pains but also thrills of that time are channeled through a rolling backbeat of Black Lips, Detroit Cobras, Brian Jonestown Massacre, The Hunches, Nirvana and new wave influences. The most surprising being glimmers of The Strokes, albeit a distressed version, on the thrashed but polished, even melodic, ‘Girls!’ And, perhaps one of the album’s best tracks (certainly most tuneful), the bedeviled ride on the 666 Metro line ‘The Sinner’, could be an erratic early Arctic Monkeys missive meets Blink 182 outtake.

The Squier is an unpretentious strop, fueled as much by jacking-up besides over spilling dumpsters, zombified states of emptiness and despair as it is by carefree cathartic releases of bird-finger rebellious fun. Reminiscing for an adolescence that isn’t even theirs, Dr. Chan’s directed noise is every bit informed by the pin-ups of golden era 80s Thrasher magazine as by Nuggets, grunge and Jon Savage’s Black Hole: Californian Punk compilation. The fact they’re not even of the generation X fraternity that lived it, or even from L.A. for that matter, means there is an interesting disconnection that offers a rousing, new energetic take. In short: Ain’t a damn thing changed; the growing pains of teenage angst still firing most of the best and most dynamic shambling music.

Brace! Brace! ‘S/T’ (Howlin Banana) 12th October 2018

Looking for your next favourite French indie-pop group? Well look no further, the colourful Parisian outfit Brace! Brace! are here. Producing gorgeous hues of softened psychedelia, new wave, Britpop and slacker indie rock, this young but sophisticated band effortlessly melt the woozy and dreamy with more punchier dynamic urgency on their brilliant debut album.

Squirreled away in self-imposed seclusion, recording in the Jura Mountains, the isolation and concentration has proved more than fruitful. Offering a Sebastian Teller fronts Simian like twist on a cornucopia of North American and British influences, Brace! Brace! glorious debut features pastel shades of Blur, Gene, Dinosaur Jnr., Siouxsie And The Banshees (check the “I wrecked your childhood” refrain post-punk throb and phaser effect symmetry guitar of ‘Club Dorothée’ for proof) and the C86 generation. More contemporary wafts of Metronomy, Mew, Jacco Gardner, the Unknown Mortal Orchestra and Deerhunter (especially) permeate the band’s hazy filtered melodies and thoughtful prose too.

At the heart of it all lies the subtly crafted melodies and choruses. Never overworked, the lead-up and bridges gently meet their rendezvous with sweet élan and pace. Vocals are shared and range from the lilted to the wistful and more resigned; the themes of chaste and compromised love lushly and wantonly represented.

This is an album of two halves, the first erring towards quirky new wave, shoegaze-y hearty French pop – arguably featuring some of the band’s best melodies -, the second, a more drowsy echo-y affair. Together it makes for a near-perfect debut album, an introduction to one of the most exciting new fuzzy indie-pop bands of the moment.

Junkboy ‘Old Camera, New Film’ – Taken from Fretsore Record’s upcoming Music Minds fundraiser compilation; released on the 12th October 2018

Quiet of late, or so we thought, the unassuming South Coast brothers Hanscomb have been signing love letters, hazy sonnets and languorous troubadour requests from the allegorical driftwood strewn yesteryear for a number of years now. The Brighton & Hove located siblings have garnered a fair amount of favorable press for their beautifully etched Baroque-pastoral idyllic psychedelic folk and delicately softly spoken harmonies.

To celebrate the release of their previous album, Sovereign Sky, the Monolith Cocktail invited the duo to compile a congruous Youtube playlist. Proper Blue Sky Thinking didn’t disappoint; the brothers’ Laurel Canyon, Freshman harmony scions and softened psychedelic inspirations acting like signposts and reference points for their signature nostalgic sound: The Beach Boys, Thorinshield, Mark Eric, The Lettermen, The Left Bank all more an appearance.

A precursor to, we hope, Junkboy’s next highly agreeable melodious LP, Trains, Trees, Topophilia (no release date has been set yet), the tenderly ruminating new instrumental (and a perfect encapsulation of their gauzy feel) ‘Old Camera, New Film’ offers a small preview of what’s to come. It’s also just one of the generous number of tracks donated to the worthy Music Minds (‘supporting healthy minds’) cause by a highly diverse and intergenerational cast of artists. Featuring such luminaries as Tom Robinson, Glen Tilbrook and Graham Goldman across three discs, the Fretsore Records release coincides with World Mental Health Day on the 12th October.

Sitting comfortably on the second disc with (two past Monolith Cocktail recommendations) My Autumn Empire, Field Harmonics and Yellow Six, Junkboy’s mindful delicate swelling strings with a hazy brassy, more harshly twanged guitar leitmotif beachcomber meditations prove a most perfect fit.

Earthling Society ‘MO – The Demon’ (Riot Season) 28th September 2018

Bowing out after fifteen years the Earthling Society’s swansong, MO – The Demon, transduces all the group’s various influences into a madcap Kool-aid bathed imaginary soundtrack. Inspired by the deranged Shaw Brothers film studio’s bad-taste-running-rampart straight-to-video martial arts horror schlock The Boxer’s Omen, the band scores the most appropriate of accompaniments.

The movie’s synopsis (though I’m not sure anyone ever actually wrote this story out; making it up in their head as they went along more likely) involves a revenge plot turn titanic spiritual struggle between the dark arts, as the mobster brother of a Hong Kong kickboxer, paralyzed by a cheating Thai rival, sets out on a path of vengeance only to find himself sidetracked by the enlightened allure of a Buddhist monastery and the quest to save the soul of a deceased monk (who by incarnated fate happens to be our protagonist’s brother from a previous life) killed by black magic. A convoluted plot within a story of vengeance, The Boxer’s Omen is a late night guilty pleasure; mixing as it does, truly terrible special effects with demon-bashing Kung Fu and Kickboxing.

Recorded at Leeds College of Music between November 2017 and February of 2018, MO – The Demon is an esoteric Jodorowsky cosmology of Muay Thai psychedelics, space rock, shoegaze, Krautrock and Far East fantasy. Accenting the mystical and introducing us to the soundtrack’s leitmotif, the opening theme song shimmers and cascades to faint glimmers of Embryo and Gila; and the craning, waning guitar that permeates throughout often resembles Manuel Göttsching later lines for Ash Ra Tempel. By the time we reach the bell-tolled spiritual vortex of the ‘Inauguration Of The Buddha Temple’ we’re in Acid Mothers territory, and the album’s most venerable sky-bound ascendant ‘Spring Snow’ has more than a touch of the Popol Vuh about it: The first section of this two-part vision features Korean vocalist Bomi Seo (courtesy of Tirikiliatops) casting incantation spells over a heavenly ambient paean, as the miasma and ominous haze dissipates to reveal a path to nirvana, before escalating into a laser whizzing Amon Duul II talks to Yogi style jam. The grand finale, ‘Jetavana Grove’, even reimagines George Harrison in a meeting of minds with Spiritualized and the Stone Roses; once more setting out on the Buddhist path of enlightenment.

Sucked into warped battle scenes on the spiritual planes, Hawkwind (circa Warriors On The Edge Of Time) panorama jams and various maelstroms, the Earthling Society capture the hallucinogenic, tripping indulgences of their source material well whilst offering the action and prompts for another set of heavy psych and Krautrock imbued performances. The Boxer’s Omen probably gets a much better soundtrack than it deserves, as the band sign off on a high.