ALBUM/BOOK: DOMINIC VALVONA

PHOTO CREDIT:: Marilena Umuhoza Delli

Introduction:

Despite the multiple Grammy-award nominations and wins, and a reputation for capturing some of the most mesmeric, raw and sublime performances in the most dangerous of locations, Ian Brennan is often self-deprecating about his (obvious) talents as a producer. Ian would have us believe he merely turns up and presses the record button; that his ‘field-recordings’ are entirely serendipitous. And in some ways, this is part of his underlying philosophy: removing himself from each recording so that the emphasis is wholly on the performance. Preferring to travel (when possible) to the source, each of Ian’s recording sessions are unique and truthful.

Loosened and set free from the archetypal studio, Ian’s ad hoc and haphazard mobile stages have included the inside of a Malawi prison, Mali deserts, and the front porches and back rooms of Southeast Asia: one of which was on the direct flight path of the local airport. And yet that is only a tiny amount of a near forty release back-catalogue recorded over just the last two decades.

As if being a renowned producer of serious repute wasn’t already enough, Ian could also be considered a quality author; so far publishing four digestible tomes on a range of music topics and regularly contributing to a myriad of publications. He’s turn of phrase and candid nature brings music, the relationships, and journeys to vivid life, whilst never blanching from describing the harrowing, disturbing and traumatic realities of the geo-political situations, the violence. As a violence prevention expert, advocate, Brennan’s recordings can be said to act as both testament and a healing process.

His partner in all these projects is his wife the Italian-Rwandan photographer, author and filmmaker Marilena Umuhoza Delli, who documents each trip.

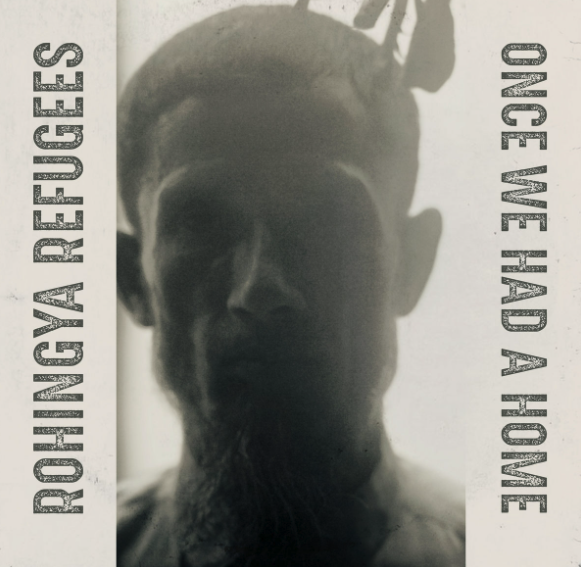

The couple’s latest project once more draws attention to a forgotten people in crisis, recording the voices of the persecuted Rohingya: terrorised and ethnically cleansed by the Myanmar government and military. A stateless population forced to flee from their age-old home in the country’s Rakhine state, a million of this ethnic group currently live in the world’s biggest refugee camp over the border in Bangladesh.

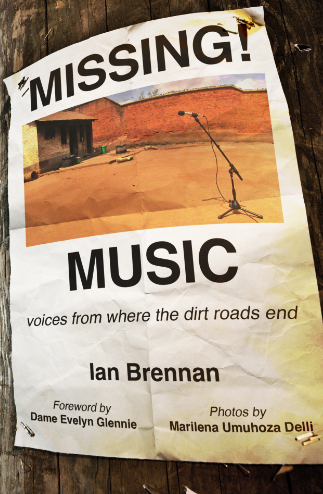

Almost simultaneously, Brennan (with Forwards from both Delli – who also provides all the photography – and the widely acclaimed percussionist Dame Evelyn Glennie) has also brought out a new book. Part “impressions”, part exploits, and part ethnography without the cliché and stiff academia, Missing Music: Voices From Where The Dirt Road Ends is a personal semi-autobiography of a lifetime’s recording work and travels; complete with polemics on the state of the world and music industry at large.

Rohingya Refugees ‘Once We Had A Home’

As attention spans seem to contract and the 24-hour newsfeed cycle is forced to update and move on every nanosecond in the battle to retain minds and lock in followers for monetary gain and validation, many geopolitical events – once seen as cataclysmic and about to push the world into climate crisis or war – seem to be quickly forgotten, usurped and replaced by the next teetering-into-the-abyss flashpoint. And so, I say, “remember the Rohingya genocide?” Of course you don’t. That’s old news. We’ve had COVID, the cost-of-living crisis and high inflation, Russia’s barbaric invasion of the Crimea and Ukraine, the continuing incursions of Islamic terrorism in Africa, the ongoing conflict and ethnic-cleansing the Tigray by Ethiopia and Eritrea, and now, since the horrific vile attacks on Israel on October 7th by Hamas, another ongoing escalating conflict in the Middle East: including Israel’s total war strategy of bombardment and eradication, and siege of Gaza. Chuck in AI and China (will they, won’t they soon invade Taiwan) and the spectre of Iran suddenly launching a full-on campaign in the region, and the hyperbolic heavy load of world problems seem too large to quantify and process, let alone solve.

Thankfully Brennan and Delli do their utmost in the face of such ignorance and crisis fatigue to draw attention to one of the world’s worst forced movements of people. Escaping what has been defined in international law as genocide – accusations the Rohingya’s oppressors Myanmar face in the International Court of Justice in The Hague – the Rohingya ethic grouping of people claim their descendance from 15th century Islamic traders. But it’s thought that they probably arrived in what is now Myanmar (formerly Burma) via various historical waves of migration over time: from the ancient to Medieval. The Buddhist majority Myanmar’s history is full of origin stories and diversity. The government has its own list of “national races” no less: a 135 in total. Missing from that list however, the near wholly Muslim practicing Rohingya are referred to as “illegal migrants”; mere squatters on the land they’ve cultivated and shared for at least a millennium.

Dating back to the 1970s, the military juntas – the more recent short flirtation with a less than democratic system, now looking like nothing more than a blip, a footnote in the country’s story – have constantly persecuted this group, which before the genocidal campaign of 2017 numbered 1.4 million or more. Essentially stateless, and hunted down, displaced, a vast majority are confined to the world’s largest refugee camp in Bangladesh: although many have fled much further abroad and throughout more accommodating South-eastern Asian countries. A sick twist to this persecution and removal, the Myanmar military are forcibly conscripting the Rohingya to help fight an ongoing conflict with the Arakan Army in the region of the Rakhine State. Founded in 2009 to win self-determination for themselves, the Arakan are yet another convoluted thread to the story of woe; another ethnic group fighting to achieve their aims. And just to muddy the waters even more, the Arakan Army also features the Rohingya amongst its ranks.

Myanmar’s government would in their defence cry foul, that they were fighting insurgents, illegals, and terrorists. There have been incidents up and down the border, with the murder of police and military by both groups. And the Arakan have embarrassed the military, winning huge swathes of the Rakhine against a far superior and numerical army.

Within the makeshift camps, set up in the aftermath of Myanmar’s most brutal act to date – the full-scale programme of ethnic cleansing from its lands -, gangs roam and prey on the vulnerable eking out an existence in the face of extreme poverty and limbo. The future looks bleak, even with international condemnation, with no hope of return, of justice. In highlighting “hidden voices” and finding the rawest of accounts, their both poetically sung, and achingly voiced testaments are recorded for posterity by Brennan, who’s hands-off approach removes the barriers between recordist and performer. Ernest collected ethnography can take a walk, for this is above all about bringing authenticity and the marvels of the untainted, uncollyed and (cliché as it is, it still stands) the truthful to our ears. Because the remarkable thing about all of Brennan’s work is the way he introduces us all to revelatory sounds and connections.

Within the refugee camp, and despite the severe conditions, most of the recordings are incredibly lyrical and melodic to the ear: even when the musical accompaniment of percussive chings and shakes, entwinned plucks and occasional singular wooden box-like hits are minimal. Musically crossing borders with every caress, strike and either brassy or percolated drone, you’ll hear elements of the Islamic, of India, the Caucuses, Pakistan, Indonesia, Thailand and of course Myanmar. And despite the traumatic subjects, the crimes against humanity, even the harrowing testament can sound like an intimate courtly piece of theatre or a purposeful, softly placed dance. That goes for the yearning, near pleaded declarations of love for both soul mates and home too – although without the context, one echoed aching soul’s declaration, if unrequited or stopped, threatens to “hang” themselves.

The titles of these recordings certainly pull you back into the reality of their desperate plight, with reminders that this campaign against them is fuelled in part by religious nationalism (‘The Soldiers Burned Down Our Mosque’), but that sexual violence is a common weapon in that persecution (‘Let’s Go Fight The Burmese (They Raped Our Women))’.

As with most of these projects the revelation is not only in hearing such original and moving voices but in picking up what could be the very roots of musical forms that we’ve taken for granted or taken as our own. The soulfully lamentably exhaled ‘My Family Prays For Us To Come Home (Here We Have No Life At All)’ I swear has the very seeds of gospel music and the blues within its Rohingya folk traditional soul. And I seriously swear I can detect a Catskills-like banjo on ‘Let’s Go Fight The Burmese (They Raped Our Women)’ . It’s obviously not of course, as I’m sure it’s an instrument more native the climes and geography of Southeast Asia than Americana.

Once more it’s beauty that shines through the distress; the musicality of burning hope in the face of anguish and violence still connecting and making heart’s sing. Brennan’s minimal interference (although that’s not really the right word for it) allows for the most pure, candid, and unforgettable of raw performances. Without overdoing it, or using too many superlatives, these projects are amongst the most important documents of their kind; bringing the harsh realities of the forgotten Rohingya people to public notice in the hope that their story is heard: we can’t pretend we never heard it!

Book: Missing Music – Voices From Where The Dirt Road Ends (PM Press)

Ian Brennan has a real knack for writing; a visceral way of setting the scene, the danger and geo-political circumstances and context without succumbing to boring platitudes or stiff academic dullness. He certainly can’t be accused, unlike so many “worthy” signally publications and sites, of sucking the soul out of the music he writes about; like all the best writers, someone who actually loves music in all its forms. Brennan the celebrates what cannot be quantified or bottled: or for that matter sold! In fact, you could say he was in a continuing, constant, battle against the corporate forces of greed and consumerism, riling at the commodification of art.

Brennan has written several books in support of artists outside the Western sphere of influence, whilst also attacking the onslaught of “muzak”. But. How you open up ears and widen the appeal of independent voices and those musical forms from such far-flung pockets of the world as Cambodia, Malawi or São Tomé is anyone’s guess: I’ve tried for over two decades, finding it a total myth that each new generation, growing up in the age of the Internet and with access to the world’s music catalogue at the swipe of a screen, is somehow more eclectic – the short answer is, no they are not.

The horrible and lazy “world music” term – as Brennan would say, “all music is world music” – fetishizes those it seeks to label. But then again, plenty have tried to celebrate and promote those same voices and artists” WOMAD being the most glaringly obvious example, but literally 1000s of labels, from major to cottage industry independents. And yet, even as certain names fly, take hold, and capture Western audiences and build up sizable numbers online, they’re demoted to playing the “world stage”: demarcated and separated. If anything, we’ve gone backwards, with the main events dominated by the so-called “urban” stars, vacuous tiktok sensations and heritage acts (not wholly “white” I might add). Gone are the days when Kuti could share the same space as some Western rock act; even jazz, no matter the constant bullshit promoted trend to declare its renaissance and popularity, can’t get a main stage slot at any major festival. Don’t get me started on the advancing AI takeover of the arts and music; the future already here as thousands spend a fortune to see avatars of stars still alive and able to perform – namely that God awful ABBA production; the quartet rendered by tech to appear eternally youthful and at their peak. Now every artist is forced to compete with everyone whoever existed, dead or alive, for attention and support. In that climate Brennan champions a far humbler cast of artisans and amateurs alike, from the incarcerated soulful voices of the Mississippi penal system to the late North Ghanian funeral singer Mbabila “Small” Batoh and sagacious atavistic-channelling old folk of Azerbaijan.

Choosing just a smattering from a catalogue of at least forty releases over the last decade or more, Brennan’s latest book, Missing Music – Voices From Where The Dirt Road Ends collects together some of his most personal recording experiences. In fact, it reads in part like a winding autobiography along a road less travelled, with Brennan highlighting his older sister Jane’s struggles with Downs syndrome, whilst panning out to address the lack of social care, the stigma, and disparities at large in the American health care system. You can hear Jane’s voice and pure joy of expression on Who You Calling Slow?, recorded by Brennan and released under the Sheltered Workshop Singer title. Apart from his Rwandan recordings (his half Rwandan half Italian wife and partner on these projects, Marilena Umuhoza Delli’s family was forced to flee the genocide) I believe this project (and book chapter) is the closet and most personal to Brennan’s heart. Having to watch during the hands-off, isolated bleakness of COVID as his sister retreated into her shell, his words are a testament to the (cliché I know, but if it could be used with any real sincerity it’s here) power of music therapy.

“Just for the fuck of it” , the journey Brennan makes is an inter-personal, academic free one, with life-affirming stepovers in Suriname (‘Saramaccan Sound’), Bhutan (‘Bhutan Balladeers – Your Face Is Like The Moon, Your Eyes Are Stars’) and most rural outposts of Africa (‘Fra Fra – The Quiet Death Of A Funeral Singer’). That last chapter deals with death quite literally; marking the passing of Fra Fra’s Mbabila “Small” Batoh, who led the northern Ghanian trio of funeral singers and players. Primal, hypnotic with various sung utterances, callouts, hums and gabbled streams of despondent sorrow they personised the process of grief. But sounded like the missing thread between African roots music, the blues, and New Orleans marching bands. Incredible to hear – which you should if you haven’t already – it’s artists like “small” that Brennan truly rates: holding them up on an equal pedestal with the best the West has to offer in the roots stakes. Unfortunately, the enigmatic Djibouti artist Yanna Momina, star of the Afar Ways album of recordings, also passed away – I made a little tribute in last July’s Digest column. A member of the Afar people, an atavistic ancestry that spreads across the south coast of Eritrea, Northern Ethiopia and of course Djibouti (early followers of the prophet, practicing the Sunni strand of the faith), Momina was a rarity, a woman from a clan-based people who writes her own songs. Once more Brennan summons up the right words, expressions, and scenery in bringing her legacy to life.

More like the best of traveling companions, guides, open to adventure, Brennan’s writing balances joyous connections with the dangerous conditions in which he finds himself. Little details say so much in this regard, with the almost incidental sentence and anecdote about being cautioned to not use his first name of Ian because it sounded Armenian, when crossing the flashpoint and stepping into the continuing conflict between that country and Azerbaijan to record ‘Thank You For Bringing Me Back To The Sky’. But of course, when out of choice, traveling to such danger spots is either lunacy or brave, and along the way there’s plenty of discouragement and warning.

Anything but a thrill seeker, Brennan’s role in violence prevention makes it a vital part of his job; gaining a better understanding and knowledge from the horse’s mouth so to speak. Many of his impromptu sessions are therapeutic in allowing victims to speak about their trauma in the most unsympathetic of climates. The very roots of all Western music no less, Brennan freely comments on the disparity of fortunes between the artists detailed in his book and those in the English-speaking West – a language, statistically that sells more volumes and traction than any other. Arguments and studied polemics are made, politics auspice and solutions put forward against the blandification of the music industry and our environment – for example, why do so-called hip independent signalling businesses, such as cafes play such uniform bland, enervated and commercial music that’s the very opposite of their principles and mantra; Brennan says we shouldn’t take that crap and point it out to the barista the next time this background soundtrack insults our ears.

Of those “timeless voices”, which should be amplified, this little passage is one of the best: “Rather than seeking charity, theirs is the charitable act – truth offered without expecting anything in return. The only desires, connection.”

As a celebration that faces the hard truths, this book is a must read and guide to new and more deserving sounds from around the world; for these artists have more going for them, are closer to the pure soul, motivation and expression of music than the majority of fake acts and vaporous stars that do unfortunately dominate the airwaves and social media.

Ian Brennan on the Monolith Cocktail: Check out just a smattering of his projects I’ve reviewed, plus a very special interview from a while back.

Tanzania Albinism Collective ‘White African Power’

Witch Camp (Ghana): ‘I’ve Forgotten Now Who I Used To Be’

The Good Ones ‘Rwanda…You See Ghosts, I See Sky’

Ustad Saami ‘Pakistan Is For The Peaceful’

Sheltered Workshop Singers ‘Who You Calling Slow?’

Comorian ‘We Are An Island, But We’re Not Alone’

The Oldest Voice In The World (Azerbaijan) ‘Thank You For Bringing Me Back To The Sky’

ALBUM PURVIEW/CONTEXT: DOMINIC VALVONA

‘Parchman Prison Prayer – Some Mississippi Sunday Morning’

(Glitterbeat Records) 15th September 2023

Back in the state penitentiary system, the producer, author and violence prevention expert Ian Brennan finds the common ground once more with another cast of under-represented voices. Eight years on from his applauded, Grammy nominated Zomba Prison Project, Brennan, thousands of miles away from that Malawi maximum-security facility in the deep, deep South of America, surprises us with an incredible raw and “uncloyed” (one of Brennan’s best coined interpretations of his production and craft) set of performances of redemption and spiritual conversion.

On the surface, what connects that Zomba experience and this Sunday service communal at the infamous Parchman Prison in the Mississippi Delta is less a somber woe me sense of bitterness at incarceration, but a documentation of endurance and spirit. In fact, the inmates of Parchman seem, or the individuals put on tape and prosperity, to face up to their crimes, misdeeds; a self-realisation you could say. Most of this is down to finding religion; in this setting, and with the history, it’s Christianity – although no actual denomination is mentioned, its fairly obvious we’re talking the Baptismal, Evangelical kind that fires up the soul and glorious magic of Gospel music in the Black communities of America. In many ways, with suspicion and well-founded doubt, this paean, celebration of God and Jesus is routinely sniffed at or dismissed; the premise of salvation mocked even, and constantly skewered to certain groups, individuals own selfish purposes. Musically, this tradition has undeniably given birth to some of the greatest sounds and voices in the American music cannon; a sanctuary to find understanding and guidance in the face of oppression and racism. It’s difficult for many of us to understand faith, but there’s no way you can’t be moved by Arthea, the Staple Family and Sam Cooke (to name just a few of those hot-housed in the church). And although we’re not told of their crimes, their sentences (remember this is a prison that includes both a men’s and women’s death row), you can’t help but be moved by the inmates on this testament to spiritual salvation.

For some context, Parchman squats across 28sq miles of unconventional farm-like enclosures near to the uninhabitable swamps of the Delta, but also within shouting distance of the Blues map of iconic landmarks and civil rights flashpoints. In the former camp, the birthplace of Muddy Waters, Ike Turner and Sam Cooke (in nearby Clarksdale), and the place where Bessie Smith breathed her last and junction where Robert Johnson signed over his soul to the Devil. In a nutshell, the very birthplace of Blues as we know it. And if we go even further back, the conjuncture of at least two First Nation routes across the South. In the latter camp, Parchman is a “hop” and “skip” away from the gruesome, evil racist torture and murder (eventually lynched) of Emmett Till in 1955. That’s some psychogeography right there.

PHOTO CREDIT: Marilena Umuhoza Delli

The inmate population of the prison is mixed, with racial tensions resulting in some forms of segregation. Statistics wise, its ranked as one of the worst prisons for mortality rates and rioting. Improved, depending on who you listen to or read (Jay-Z was moved and enraged enough to back and file a class action suit against the “barbaric conditions” of this prison not all that long ago), Parchman was once run more or less like a private fiefdom, with prisoners routinely worked to near death; the Black inmates picking cotton, back in servitude and chains as if emancipation had never happened. This was Jim Crow country after all. A bleak environment to put it mildly, it formed the backdrop to Bukka White’s (one in a long line of Bluesman, Rock ‘n’ Rollers, Bluegrass and Country luminaries that spent time there) forewarned ‘Parchman Farm Blues’, to Faulkner’s The Mansion (christened with forebode by the author as “destination doom”) and Jesmyn Ward’s award-winning 2017 novel Sing, Unburied, Song. They based prisons in both Cool Hand Luke and O Brother Where Art Thou? on it too.

Whilst Brennan, as part of his ongoing acclaimed series of “in-situ” recordings around the world (mostly in some of the globe’s most dangerous and remote locations) with his filmmaker, photographer and activist partner Marilena Umuhoza Delli, hones in on just one such scandal hit prison, he’s shining a light on America’s entire prison system; its laws, sentencing and the disparity in incarcerating those from the Black population. Funds from bandcamp pre-sales for example went towards the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.

In answer to the intergenerational strife of racism in America, the voices on this album turn to the Gospels; guided by the prison’s chaplains, although services are in some cases segregated: but not here.

It took three years of bureaucracy to unlock the cell doors, and much apprehension, but Brennan’s skills in diplomacy eased the way for candid, pure performances; both a capella style and with the accompaniment of instruments from the prison chapel. And as ever, with minimal fuss the he captures some stark epiphanies, afflatus revelations and paeans from a cast of both partially identified and anonymous prisoners. The oldest of which, the seventy-three year old former rock ‘n’ roll singer turn chaplain, C.S. Deloch, who offers one of the most poignant quotes: “You’ve got to get out of prison while you’re still in prison”. That former life comes in handy as Deloch leads the congregation on the Muscle Shoals gospel (via Jamaica) ached ‘Jesus, Every Day Your Name Is The Same’, and the final group effort, hallelujah clapping with Fats Weller piano jangling, ‘Lay My Burden Down’.

Past lives for the most part are kept secret, but as you listen to those unfiltered (ok, the odd bit of echo here and there) humbling songs it becomes apparent that there isn’t any distinction or difference in quality to those professionals on the outside. The twenty-nine year old L. Stevenson, stripped back to nothing, has such a soulful reverence on ‘Open The Eyes Of My Heart, Lord’. And on the handclapped, iterated ‘I Gotta Run’, he performs a brilliant doo-wop-esque turn, complete with lower frog-like register bass. One anonymous participant sounds like John Legend, on the beautifully yearned love paean, ‘I Give Myself Away, So You Can Use Me’ – a real highlight that if buried on any compilation would have been assumed to be from some pianist-singer R&B troubadour of repute.

You could hear L. Brown’s ‘Hosanna’ litany being used as a hip-hop sample by Jay Z or the dodgier Kayne West – who’s had is own flirtations with the good book and gospel music.

Surprisingly, the only actual proto-rap inclusion on this album is the Robinson and A. Warren collaboration ‘Locked Down, Mama Prays For Me’, which combines a sympathetic soulful hum with a spoken word walk through of shame. There are rumminations on the hurt caused, and the machismo that comes with the territory, plus a special heartfelt apology to his mum.

PHOTO CREDIT: Marilena Umuhoza Delli

The sixty-three year old N. Petersen wades in the waters on the Holy Land baptismal Galilee, transferred to the Mississippi bayou, ‘Step Into The Water’, whilst A. Warren’s second appearance, ‘Falling In Love With Jesus Was The Best Thing I’ve Ever Done’, has a real Willis Earl Beal vibe. The most unusual recording is by the sixty-year old M. Palmer, who’s deeper than deep throaty baritone is almost mystical on ‘Solve My Mind’; especially with what appears to be a reverberated otherworldly drone accompaniment.

There’s music, song and litany that would be recognizable to inmates from the turn of the last century, whilst others, tap right into the modern age. The Gospel’s message runs deep in the Southern realms, and encouragingly seems to motivate even those with little hope of being released. Hard times are softened by belief and redemption on a revelatory production. Returning to America after a myriad of recordings throughout the world’s past and present war zones, scenes of genocide and remote fabled communities, Brennan finds just as much trauma and the need for representation back home.

Hi, my name is Dominic Valvona and I’m the Founder of the music/culture blog monolithcocktail.com For the last ten years I’ve featured and supported music, musicians and labels we love across genres from around the world that we think you’ll want to know about. No content on the site is paid for or sponsored and we only feature artists we have genuine respect for /love. If you enjoy our reviews (and we often write long, thoughtful ones), found a new artist you admire or if we have featured you or artists you represent and would like to buy us a coffee at https://ko-fi.com/monolithcocktail to say cheers for spreading the word, then that would be much appreciated.

Our Daily Bread 567: The Oldest Voice In The World (Azerbaijan) ‘Thank You For Bringing Me Back To The Sky’

April 3, 2023

ALBUM PURVIEW SPECIAL

Dominic Valvona

CREDIT: Marilena Umuhoza Delli

The Oldest Voice In The World (Azerbaijan) ‘Thank You For Bringing Me Back To The Sky’

(Six Degrees Records) 6th April 2023

There can be few remote corners of this well-traversed globe left unrecorded, yet the celebrated polymath and renowned in-situ recordist Ian Brennan and his wife, but most importantly partner on these sonic expeditions, the filmmaker and photographer Marilena Umuhoza Delli, have found one such spot on the Azerbaijan border with Iran. So remote in fact, almost untouched by modernity and technology, that the language spoken in this mountainous village is almost unintelligible to even those living in the valley below.

Settled by the atavistic Talysh people of this region, this outlier of naturalistic and hardened living is an ancient place with challenging origins shrouded in thousands of years of obscurity. Perhaps ancestors of the old Iranian tribe the Cadusii, this unique ethnic community, clinging and camped out on the southern mountains of Azerbaijan, is famous for its longevity; said to be the home of the oldest ever recorded human, at (an allegedly) 168 years old! But despite that remoteness, the ever encroaching dreaded Covid-19 pandemic found its way there, and by the time Brennan and Delli travelled to this outcrop, the number of centenarians had diminished greatly. As if the pandemic wasn’t tragic enough, our sonic explorers found that the living conditions for these elders were extremely harsh: no indoors plumbing, forced to sleep on floorboard mattresses. And so this project, just the latest in at least fifty recordings by Brennan, became an antidote of a kind to anti-ageism.

As dangerous places, states in flux and aftermaths of genocide go, compared to many of Brennan’s tour-of-duties (Rwanda, Vietnam, Cambodia, Pakistan etc.) Azerbaijan, on the surface, seems a far less hostile safer bet. However, that Southern Caucus region’s decades old fight with its western neighbor Armenia over the complicated and disputed landlocked Nagorno-Karabakh region (the Armenian’s refer to it instead as the Artsakh) reared its ugly head again in 2020; only brought to a conclusion (of a sort) by a trilateral agreement overseen by Russia in November of that year. In a window of opportunity Brennan and Delli made the trek in late 2021. Just months later, Russia would of course invade Ukraine.

CREDIT: Marilena Umuhoza Delli

What they both discovered and recorded for posterity is a most incredible document of elderly sagacious voices very much alive, yet all to aware of their own mortality. Surviving COVID but left to mourn those that didn’t, this should be a lamentable, saddening proposition. Far from prying in on a collective trauma, with a number of the performers obviously distraught and in a state of anguish at times, Brennan’s hand was indeed kissed by a long-since retired shepherd, who repeated his gratitude (giving the album its title in the process): “Thank you for bringing me back to the sky”.

This album could, like so many previous recordings in this vain, be said to act as a sort of therapy; a release. It certainly isn’t in the spirit of Lomax, saving old voices before they disappear; an ethnomusicologist exercise in Western preservation. As a subtle augmentation of elements are added, with some vocal performances, aches and talks further transported by a number of past Brennan collaborators (Kronos Quartet, Tinariwen, The Good Ones and Yoka Honda) on the bonus tracks.

For those new to Brennan’s hands-off approach, the set-up is as un-intrusive and natural as possible. The surrounding environment isn’t just welcome to bleed into each recording but invited. This translates into the creaking of a door; the crackled flames of a furnace; and in the case of the afflatus-touched ‘Lullaby’, what sounds like a rhythmic trudge through water.

Whilst most expressions, deliveries of earthy travail and more heavenly thanksgiving are pretty stripped back, soft but effective uses of mirrored and echoed reversals are used on the warped piano yearned ‘My Mother Lived To Be 110’, and the more avant-garde piano and spoken ‘The Young Men Are Sent To Die In Rich Man’s War’. This turns some recordings into portals to other worlds, others, like something from Zardoz, or even psychedelic and otherworldly.

Voices are effected on the reverberated, forewarned ‘Son, Don’t Go There, The Road Is Dangerous’, turning a couple of different vocals into something both giddy and esoteric. I haven’t asked or searched it out so do forgive my ignorance, but the poetic ‘You Are A Flower Yet To Grow’ sounds like it has some kind of accompanying bassoon blowing away on it; and ‘Pepe, Pepe (Donkey Song)’ features what I can only describe as a sort of primitivism jazz horn. There’s hand drums being respectively rattled and hit on the longer, lyrically melodious dance, ‘Bulbul (Nightingale)’ and the more Persian sounding ‘Screaming From The Mountain Top For My Son’.

CREDIT: Marilena Umuhoza Delli

Amongst the often more distressed offerings and terms of abandonment, wise advice to longevity comes in the form of the trolley-full-rattled-crockery (or so it sounds) accompanied heartfelt ‘The Secret To Life: I Was Loved’, and the acoustic guitar wobbled and bandy-stringed, talked ‘The Secret To life: I Worked Hard And Ate Butter’ – dairy lovers like me take comfort; although my work rate of honest craft and toil will have to be increased considerably if that’s the case to long life.

A quartet, as I mentioned earlier, of collaborative transformations have been added as “bonus” material. All those involved have at some point crossed congruous and valuable paths with Brennan in the field or studio, the first being the Kronos Quartet who lift a sorrowful Talysh mountain border voice with a treatment of neoclassical held and bowed strings and gravitas. Yuka Honda, meanwhile, evokes Die Wilde Jagd and The Pyrolator on the sophisticated electronic and minimalist Techno affected ‘Prayer Overheard’.

One of Mali’s Tuareg luminaries of desert rock and blues, the much lauded Tinariwen, cast a near Medieval and Oriental dream spell on ‘Ghosts’, and the Rwandan farming bluesman, The Good Ones, provide an elasticated, stringy and stripped backing for the female-voiced ‘A Lifetime Still’ – complete with a light chorus of birds.

Loss, bereavement, the wise observations of those uncomplicated voices, this latest recording from Brennan and Dilli (who records each project through her lens) encourages a dialogue and offers a unique angle on ageing, or rather, the abandonment and prejudice of growing old. In a time in which we’ve grown to distrust, cast off and denigrate old age in the pursuit of eternal youth (cosmetically and through the filters of Instagram), the old are looked on with embarrassment and as a burden; their deaths on mass, as they were shunted out of hospitals into care homes to spread COVID, until recently, seen as just a unfortunate result of the pandemic. We’ve come to see ageing as a reminder of our own unwanted mortality. As I’ve said, those voices come alive in the presence of Brennan, cutting through the pretence and bullshit with the most emotionally profound wisdom and anguish of the times. With such a skilled touch, Brennan loses none of the atavistic traditions yet transforms his hosts’ song into the “now” with a near-psychedelic, otherworldly and spiritual production of folk and the avant-garde. This is quite unlike anything else you’ve heard.

Hi, my name is Dominic Valvona and I’m the Founder of the music/culture blog monolithcocktail.com For the last ten years I’ve featured and supported music, musicians and labels we love across genres from around the world that we think you’ll want to know about. No content on the site is paid for or sponsored and we only feature artists we have genuine respect for /love. If you enjoy our reviews (and we often write long, thoughtful ones), found a new artist you admire or if we have featured you or artists you represent and would like to buy us a coffee at https://ko-fi.com/monolithcocktail to say cheers for spreading the word, then that would be much appreciated.

ALBUM/Dominic Valonva

The Good Ones ‘Rwanda…You See Ghosts, I See Sky’

(Six Degrees Records) 8th April 2022

Once more returning to the rural farmlands of a genocide scarred Rwanda, producer polymath Ian Brennan presses the record button on another in-situ, free-of-artifice and superficial production. The fourth such album of unimaginable stirred grief, heartache and reconciliation from the country’s nearest relation to American Bluegrass, The Good Ones latest songbook arrives in time to mark the 28th anniversary of the Rwanda genocide in the mid-90s; a 100 days of massacre, the fastest ever recorded of its kind in the 20th century with the true figures disputed but believed to be around the million mark.

Triggered, its argued even to this day, by a history of tribal warfare, insurrection, civil war, foreign interventions and the assassination of the then president Juvénal Habyarimana, the events of that three month period in 1994 saw a sudden death cull, ethnic cleansing of Rwanda’s Tutsi minority at the hands of the majority Hutus: though even moderate Hutus, along with Rwanda’s third main tribe the Twa were also far from safe, with many caught-up, trapped in the ensuing bloodbath.

Barbaric beyond any semblance to humanity, victims were brutalized, raped, cut to ribbons or herded together in buildings, churches, and schools and burnt alive. Unlike so many previous genocides however, most of those victims were murdered by hand with machetes, rudimental tools, weapons and gallons of Kerosene. No family was left untouched, with both The Good Ones dual roots vocalist set-up of Adrien Kazigira and Janvier Havugimana both losing loved ones, siblings and relatives.

On the remote hilltop farm where he was born and still continues to work, but record too, Adrien managed to hide and survive. But Janvier lost his older brother, a loss felt considerably by the whole trio who looked up to him as an early musical mentor. As a healing balm all three members, including the as yet unmentioned Javan Mahoro, all represent one of Rwanda’s main three tribes: Hutus, Tutsi and Twa. And so bring each culture together in an act of union, therapy and as a voice with which to reconcile the past.

Instantly drawn to the band during a research trip in 2009, Ian recorded their debut international album and the subsequent trio of records that followed: 2015’s Rwanda Is My Home, 2019’s Rwanda, You Should Be Loved, and now in 2022, Rwanda…You See Ghosts, I See Sky. Ian’s wife and longtime partner on both this fourteen-year recording relationship and countless other worldly projects, the filmmaker, photographer, activist, writer Marilena Umuhoza Delli was the one to instigate this Rwanda field trip. Marilena’s mother herself ended up immigrating for refuge to Italy, her entire family wiped out..

In between numerous productions in dangerous and traumatized spots (from Mali to Cambodia and Kosovo) the partners recorded the fourth volume of Glitterbeat Records Hidden Musics series in Rwanda (back in 2017); bringing the incredible stirring songs, performances of the country’s Twa people (or pygmy as they’re unfortunately known; bullied and treated with a certain suspicion by others) to a wider audience.

Back again on Adrien’s farm and haven, this quintet was reunited to record a thirty-song session. Already receiving accolades aplenty in the West, working with an enviable array of admirers, from Wilco to TV On The Radio, Gugazi, Sleater-Kinney and MBV, it’s extraordinary to think that these earthy harmonic songs were produced in an environment without electricity; music that’s made from the most rudimental of borrowed farm tools in some cases.

The true spirit of diy, raw emotion, The Good Ones speak of both love and the everyday concerns facing a population stunned and dealing with the effects of not only that genocide but the ongoing struggle to survive economically. The album begins on a reflective tone of disarming hope however, with the tinny scrappy cutlery drawer percussive and rustic natty-picking bluegrass leaning, ‘The Darkness Has Passed’. From the outset those beautiful of-the-soil sagacious and honest vocals and harmonies prove moving and powerful. Whilst songs like the Afro-Cuban and bluesy bandy turn ‘Columbia River Flowers’ sound positively romantic; a sentiment that also permeates the almost childlike abandon of ‘Happiness Is When We Are Together’, which sounds not too dissimilar to a sort of African version of Beefheart or Zappa. ‘Berta, Please Sing A Love Song For Me’ is another lovely romantic smooch, which features the Orlando Julius like serenades of the noted NYC saxophonist Daniel Carter.

Often, the outdoors can be heard as an integral, fourth band member, with the farmyard, cowshed gates struck like a percussive metal rhythm, as on the poetically romantic ‘Beloved (As Clouds Move West, We Think Of You)’.

Considering the themes of the last three albums, the fourth is said to be the group’s most personal yet. ‘My Son Has Special Needs, But There’s Nowhere For Him To Go’ has a more edgy tone, featuring a sort of post-punk dissonant electric guitar – almost Stooges like – and relates to Janvier’s struggle to get educational assistance for his son who has special needs. ‘My Brother, Your Murder Has Left A Hole In Our Hearts (We Hope We Can Meet Again One Day)’ makes reference to those lost in the genocide, and in this most personal of cases, a sibling but also musical mentor. Again, the sound of the rural escape can be heard, its chorus of chirping birds mingling with a banged tambourine.

Existing almost in its own musical category, its own world, The Good Ones play real raw but also melodic, rhythmic roots music that sways, resonates with vague threads of folk, bluegrass, rock, punk and even a touch of the Baroque. Ian, a man with an enviable catalogue of productions behind him, from every region of the globe, considers Adrien ‘one of the greatest living roots writers in the world, in any language’. That’s some praise; one I’m willing to believe and repeat.

The Rwanda trio expand their sound and bolster their artistic merits to produce another essential album of honest graft, heartache and longing for better times on the most incredible of songbooks.

REVIEWS ROUNDUP/Dominic Valvona

Longplayers/Extended

Spaceface ‘Anemoia’

(Mothland) 28th January 2022

Ushered in with a cosmic and exotic air flight announcement the latest disarming psychedelic pop trip from Spaceface brings the slick funk and disco party vibe to the stiff shirted cosmological experiments carried out at the CERN institute. With a vibrant sparkle and rainbow candy élan, the ever-shifting moon unit of past and present members from Flaming Lips and Pierced merge science-fact with groovy sunshine grooves on a smoothly universal album of goodwill.

Written before the pandemic at the Blackwatch Studios with producer Jarod Evans in the hot seat, Anemoia is a cocktail of good times rolled out to a soundtrack that at various points evokes MGMT, Swim Mountain, Tame Impala, the Unknown Mortal Orchestra, Sam Flex and International Pony. The halcyon funk wooed and Labrys guest spot ‘Long Time’ even comes with it’s own cocktail recipe and instructions (1oz each of Bourbon, Vermouth and Lynas, served with orange peel and on the rocks).

Guests appear in various guises throughout, from the brilliant Meggie Lennon (who recently appeared in our choice albums of the year lists) to Mikaela Davis and the sampled effects of the CERN’s scientist choir! Spaceface seem to be reaching beyond the usual themes of pop to metaphysical explorations and a sense of understanding the mind boggling theories of particle physics. It’s also seemingly all connected to the very on trend subject of identity and place in an increasingly dysfunctional uncertain world. Fear not as these concerns all melt away in a soulfully and bubbly millennial soundtrack of the cute, hippie and galactic; a plane of psychedelic pop and yacht rock funk pitched somewhere between a yoga retreat and cult space tour.

Roedelius & Story ‘4 Hands’

(Erased Tapes) 28th January 2021

Incredibly now well into his eighties the kosmische and neoclassical pioneer Hans-Joachim Roedelius is still exploring, still intrigued and still, if peaceably, pushing the perimeters of his signature forms on the piano. When not collaborating under the Qluster umbrella (just the most recent three decades adoption of the original Kluster/Cluster arc) or flying solo across the keyboard, Roedelius carefully picks projects that offer stimulus or purpose.

In this instance the self-taught composer once again crosses reflective and experimental paths with the Grammy-nominated American composer and friend Tim Story; the fifth such exercise of its kind with Story since their 2003 album Lunz.

4 Hands proves better than two, with Roedelius laying down patient, fluttered and singular noted “etudes” for Story to harmoniously refine and swell, or, to add sophisticated congruous layers until both performers phrases and playing styles become so entwined as to prove impossible to separate. Hopefully as Story comments in the notes: ‘Because it was all recorded on the same piano, the result has a very appealing consistency of sound, and hopefully blurs our individual contributions into a single integrated voice.’ I’d say they succeeded with this interplay and balance of disciplines, which at times conjures up Chopin’s no.6 etude being transformed by Cage.

This transatlantic exchange between North American and European contemporary classical movements features compositions that seem to measure time and make allusions to various instructive linguistic phrases (the relatively immediate ebb and flow opener ‘Nurzu’ derives from the German encouragement to “go ahead and do it”) and a sense of place, mood. Tellingly the resonating serial 1920s suggestive ‘Haru’ is dedicated to the late great avant-garde composer and poet Harold Budd, who just before his death in December 2020 was played this timeless peregrination.

A forty-year friendship imbues every touch and even the spaces in-between each wave, trickle, glide and tingled gesture. The very workings of this shared instrument, the pins and softened hammers are transformed into spiralled tines and fanned percussive like rhythms – sometimes evoking the Far East. A mix of improvised contours, considered tensions and nodes crisscross and flow together in a complementary fashion throughout this album of entwined synchronicity, as both artist’s read each other’s thoughts with understated adroit perfection.

From The Archive:

Hans-Joachim Roedelius Interview

‘Selbstporträt Wahre Liebe’ Review

Qluster ‘Elemente’ Review

Cluster ‘1971 – 1981’ Review

Cephas Teom ‘Automata’

(METR Music) 28th January 2021

Less Kraftwerk’s “pocket calculator” and more vintage 1980s Japanese Casio digital watch, the debut album from Cephas Teom (the atavistic etymological alias of the West Country musician and producer Pete Thomas) swims and Tokyo drifts in a solution of nostalgic Far Eastern tech. From Japanese sound gardens to retro video arcades and driving across once promising neon lit city highways of the future, Thomas evokes touches of the Yellow Magic Orchestra, Sakamoto, Yukihiro Takahashi and House Of Tapes as he ponders the quandaries of an ever encroaching technology and the wonders of A.I.

Featuring the Monolith Cocktail premiered vaporwave single ‘Tomorrow’s World’ (aired back in November of last year), Automata weaves broadcasts of figures such as Jung and the coiner of ‘cymatics’ Hans Jenny with the fatalistic voices of those drawn to extraterrestrial savior cults (such as the mass suicidal Heaven’s Gate) to present a scientific-philosophical soundtrack of both unease and nostalgia: that’s nostalgia for a society not yet disenchanted with the promises of a brighter hi-tech, computerized utopia.

Skilfully constructed Thomas emulates both the handcrafted mechanisms of Jaquet-Droz automation curiosities from another age and the dreamy airs of a dawning integrated A.I. future. It begins however with the projector-clicked lecture come chimed baubles, zappy squiggled, deep bass throbbing Japanese Zen water feature ‘Primordial Forms’, before winding up with the clicks and movements of a Sakamoto twinkled mechanized but enchanting melodic ‘Automation I’. By comparison ‘Automation II’ sees nature’s son in more pastoral surroundings, still in that contemplative garden, serenaded by classical-like drops of piano and wind chime percussion. Oh the force of the electronic Orient is strong with this one, incorporating everything from subtle hints of bamboo music, a very removed bobble of gamelan and J-pop with intricate layering of Autechre wiring, lo fi 8-bit gaming and bit-crushed effects. Surprisingly Thomas takes a kind of liquid jazz-fusion turn on the psychedelic therapy mindbender ‘Above Human’.

Solar winds blow across a circuit board tundra as Tron-like glowed vehicles cruise to the sounds of acid, techno, Manga, Namco and Sega soundtracks, veiled augurs, virtual paradises and various 80s warbles, variants and equations. A wonderful world in which to contemplate all those delusions of an automated miracle – a world in which Eagle comic’s, the BBC’s long running Tomorrow’s World programme and Silicon Valley optimistically painted as a blissful, harmonious, work-free utopia, Automata explores the networks, nodes and grids of electronic music to navigate a tricky complicated philosophical debate.

From The Archive:

Cephas Teom ‘Feet Of Clay’ Premiere

Cephas Teom ‘Tomorrow’s World’ Premiere

Mondoriviera ‘Nòtt Lönga’

(Artetetra) Available Now

You know you’re getting old when today’s young musicians consider your formative years, back in the 80s, as “nostalgic”. And so it is with Mondoriviera’s recent envisioned ‘fragmented bedtime story’ meets ‘interactive’ supernatural styled soundtrack; one of the last releases of 2021 from the insane, discombobulating ‘mondo bizzaro manufacturer’ Artetetra platform.

For this is a 80s VHS graded score of Italian folk-horror and dream-reality wrapped up in an 8-bit fantasy of crushed Super Mario Bros. platform hopping, early Warp label Aphex Twin, Darrel Fritton and Speedy J, and the combined soundtrack and gaming elements of Takafumi Fujisawas, Akira Yamaoka and Andrew Barnabas.

Unless you read all the accompanying notes you’ll miss the psychogeography apsects of this score: the mysterious cloaked figure behind this glassy spherical mirage and Elm Street dream warrior spooked world invokes the arcane, one time seat of the Western Roman Empire and Byzantine jewel, Ravenna. Quite the historical stargate with its continuous pre-Middle Ages upheavals, reputation as an early centre of Christianity, glorious architecture and mosaics it’s the city’s darker corners, the abattoir and sinister that seeps into Nòtt Lönga’s soundscape.

Strange, eerie in places, this alternative plane of retro arppegiator and algorithms and virtual reality is a nocturnal spell caught drifting and gliding between ominous fairytales and the paranormal: even alien. A disturbed 80s-style electronic hall of mirrors that draws you in with the promise of languid floating, the synthesised melodies softly come in waves before glitching like the glass screen façade of some simulation engineered by a higher intelligence from another dimension. Mondoriviera dares the listener to dream in a soundtrack theatre of his cult imagination.

Sven Helbig ‘Skills’

(Modern Recordings) 4th February 2022

The versatile (from working with such diverse acts as Rammstein to the Pet Shop Boys) East German composer-producer Sven Helbig conducts an incredible suffusion of colliery meets a minimalistic Sibelius brass on his first statement of 2022. The craftsman’s/artisan’s struggles, ‘despair’ and creative processes go through ten stages of varying reflective and plaintive stirring driven drama on an album that draws together the classical and contemporary to create an almost timeless spell.

As timeless that is as the symbolic ‘vanitas’ still life tableaus of the Dutch master Harmen Steenwijck in the 17th century; Helbig’s own modernist take on that tradition of painting places a skateboard and mobile phone next to a mortality loaded allegorical skull: the inevitable death of everything, but in this case, a symbol for the dying art of a craft and ‘skills’. As one tradition perishes another is born so to speak. But this leitmotif runs deep, right back to a pre-unified Germany, when ‘diy culture’ and craftsmanship were a necessity to those unable to afford, or even have any of the luxuries enjoyed in the West. And so Skills is a sostenuto concentrated homage to that tradition, yet also a mood board reification of the passing of time itself: the time between toil and inspiration. In a kind of Lutheran atmosphere of earnest labour, with compositions that can evoke a candlelit garret or bleak workshop in Worms, Helbig’s brass ensemble and string quartet conjure up a most beautiful gravitas that can harmoniously set hardship with the near ethereal.

Straddling the neoclassical, operatic and cinematic there’s even room for the coarser, scrunched synthesized concrete textures and pulsations of the Chicago-based musician Surachai on the album’s sober but stunning unfolding ‘Repetition’ suite.

Tunnels of daylight fall upon mechanisms and cogs as they come to life in atmospheric settings. Baubles and floating dust particles tinkle and slowly cascade gently whilst both longer and shortened strings build the tension and a French horn sounds a low, almost misty-eyed, romantic note. Luminous and dreamy on the starry ‘Vision’, and evoking the avant-garde and a touch of Kriedler on the workbench clockwork diorama ‘Flow’, the Skills album is a measured, aching and brooding work of art; a moving testament to the élan and craft of an impressive composer who’s classical roots transcend the genre.

War Women Of Kosovo ‘A Lifetime Isn’t Enough’

4th February 2022

Never ones to shy away from the harrowing atrocities committed on communities across the world, the partnership of Grammy-winning producer & author Ian Brennan and Italian-Rwandan photographer & filmmaker Marilena Umuhoza Delli have continued to stripe away all artifice and sentimentality from those victim’s stories; recording for posterity some of the most vulnerable accounts of genocide, prejudice and sexual violence in countries such as Rwanda, South Sudan, Comoros, Vietnam, Ghana and Romania. Brennan’s no fuss, in-situ style of recording has brought us unflinching accounts: the onus being on under-represented women, the elderly, and persecuted groups within under-represented populations, languages, and regions.

No less candid in this regard, the partnership’s latest collection features those nameless victims of the horrific Balkan wars of the 1990s; namely the Kosovan community of women and children raped by the aggressors as both an act of subjection, revenge, and as part of a sanctioned campaign of terror and erasure of the region’s Muslim population. Far too complicated and beyond my grasp of history to recount here, the Balkans blew up into an inter-fractional, racial, religious conflict between neighbours once kept together under the iron fist of Tito in the Slavic block of Yugoslavia, and before that, the Ottoman Empire. Once that towering force died, and with the deterioration of Soviet Russia, the region was broken up and plunged into chaos, war. On the doorstep of a practically useless EU, and with little appetite to get involved the escalation of atrocities eventually spurred the UN and NATO into action, with one of the consequences being the formulation of a separate majority Muslim state, the Republic of Kosovo – formerly part of Serbia that was until the late 80s a semi-autonomous state within that country. Admittedly this is a very glib account of events during that decade – I would recommend for further reading trying out Misha Glenny’s Balkans tome.

In what is a subject very close to both Marilena and Ian’s hearts – her only two living Rwandan relatives were born of genocidal rape, whilst Ian’s life was irreversibly impacted by the sexual assault and near murder of a loved one – the voices of Kosovo’s rape victims are given a platform in what amounts to a healing process. The trauma weighs heavy for sure, undulated as it is with the minimalistic, earthy scene-setting sounds of bells, a thrum of lamented, grieving voices, rustic scraps and some obscure stringed instruments – though there’s also some kind of odd keyboard too and a chorus of traumatic sounds that threaten to engulf the listener at one point. The record even comes with a ‘trigger warning’ (just look at the titles); the language and sentiment of those courageous survivors impossible to not take in.

Not the easiest of experiences, but then how could it (and why should it) be. We need such projects to jilt us out of our obsessive virtual realities and comfort zones; to be reminded that in many of the people who will read this review’s lifetime such post-WWII atrocities were carried out in a closeted Europe. As much a piece of activism as a sonic and vocal reminder, A Lifetime Isn’t Enough is an essential plaintive cry from a recent past that needs addressing; the consequences of which are felt every day by the women taking part, to them though this isn’t history or a footnote but an ongoing collective trauma.

From The Archives:

Witch Camp (Ghana): ‘I’ve Forgotten Who I Used To Be’.

Sheltered Workshop Singers ‘Who You Calling Slow?’

Tanzania Albinism Collective ‘White African Power’

The Ian Brennan Interview.

Letters From Mouse ‘Tarbolton Bachelors Club’

(Subexotic Records) 28th January 2022

You can forgive most Scots for the dewy-eyed worship of the unofficial national bard, Robert Burns. After all, every tartan decorated rousing of nationalism, and every lowland toiled symbolic feature of Scotland is run through with the verses of the 18th century poet/lyricist. There’s even a secondary-like New Year type holiday in his name, celebrated up here in Scotland – Burns Night on January 25th.

All roads, threads and references certainly lead back to Burns on Steven Anderson’s latest typographic contoured and fantasised album, the Tarbolton Bachelors Club. The follow-up to his previous window view An Gàrradh album, released under the Burns inspired Letters From Mouse alias, could be described as a psychogeography that takes in prominent locations, the spaces and essence of the venerated subject without all the bagpipes and kilt adorned folklore. Instead, Anderson weaves a captivating, thoughtful ambient, trance and ambiguous electronic soundtrack, both dreamy and with a touch of gravitas: Not so Scottish, glinting and fanned radiant spokes are spindled with an air of the Far East – like a pastoral mirage Masami Tsuchiya – on the opening track ‘Elizabeth’.

Traces of Burns history, brought into our world through a portal, are suffused with a touch of mystery but also beauty: none more so, again, than on that opening softly majestic sentiment to Burns daughter ‘Bess’, the first illegitimate child he had after an affair with his family’s servant girl Elizabeth Paton. Bess appears most notably immortalized in her father’s famous poem, Love-Begotten Daughter as “Lily Bonie”, a line used later on as a track title.

The album title is itself a reference to Burns quasi-masonic gentlemen’s club; a haven for debate and discussion on all the hot topics of the day. There was even a token produced to commemorate this infamous lodge, as alluded to by Anderson on the golden breathed ‘Tarbolton Penny’. Tarbolton for those unfamiliar with the great bard’s locality is a village in South Ayrshire, a county in which the romanticist was born and spent much of his life roaming.

Of course, you can’t construct such an escapist soundtrack without featuring some of Burns actual words; ghostly emerging as they do from the esoteric folk wafts of ‘South Church Beastie’, a past reminder of Burns adoration and forewarning idealised social covenant with nature and classless egalitarianism. Almost in its full version, ‘A Man’s A Man For A’ That’ – a scornful in places stab at those unwilling to rock the boat, carrying on with bowing their heads and doffing caps to their pay masters, although he was one of them himself, the poetic farmer, landowner – is read out to the Eno-esque synthesised curtain call of the same name.

Echoes of Artificial Intelligence Warp, Charles Vaughen, Tangerine Dream, Bradbury Poly and Library music permeate a chimed soundtrack of map coordinates, scenes viewed from propeller powered aircraft, vacuums and walks as Anderson offers a semi-Baroque meets late 20th century abstract vision of a thoughtful, magical sonic historiography. Anderson proves that the ghosts of that period still have much to share; a resonating voice brought back from the enlightenment with an evocative soundtrack to match.

Compilations…

Various ‘Mainstream Funk’

(WEWANTSOUNDS) 28th January 2022

The specialist rare finds and vinyl reissue label WEWANTSOUNDS first release of 2022 is another dip into the vaults of the, crate-digger’s and breakbeat connoisseur’s favourite, Mainstream label.

Bob Shad’s original “broad church” imprint grew out of an already 30 year spanning career when it took shape in the 1960s; a showcase for prestigious artists, session players and Blue Note luminaries chancing their arm it the bandleader or solo spotlight. A musical journeyman himself, Shad (whittled down from Abraham Shadrinsky) began his producer’s apprenticeship at the iconic Savoy label, then moved to National Records before taking up an A&R role at Mercury, where he launched his own, first, label EmArcy. It was during this time that Shad would produce records for the venerated, celebrated jazz singer deity Sarah Vaughan, the Clifford Brown & Max Roach Quintet, Dinah Washington and The Big Brother Holding Company.

As a testament to his craft, Vaughan would go on to record eight albums on Shad’s Mainstream label, the next chapter, leap in a career that traversed five decades of jazz, soul, blues, R&B, rock, psych and of course funk. Mainstream’s duality mixed reissues (from such iconic gods of the jazz form as Dizzy Gillespie) with new recordings; with its golden era arguably the five-year epoch chronicled in this latest compilation. From the first half of the 1970s, WEWANTSOUNDS has picked out twelve nuggets of varying quality, starting with Vaughan who leads the pack with a classy, showy jazz-soul cover of one of Marvin Gaye’s career-defining classics, the downtown social commentary ‘Inner City Blues’. Oozing sophistication amongst a soft tangle of horns and funky licks, the rightly venerated jazz soulstress barely breaks a sweat. Following that icon is the “underrated” alto/tenor saxophonist Buddy Terry with the ten-minute plus jazz-funk exotic peregrination turn workout ‘Quiet Afternoon’, which proves anything but a gentle meander in the park. Probably of note for the appearance of Stanley Clarke, this burnished sun-lit turn changes signatures from the relaxed to a “pure” dynamic free fall of free bird flighty flutes, screaming horns and infused exotic jazz-fusions. An epic of the form this should prompt further investigation of Terry’s small back catalogue – that’s two albums for Mainstream, and not much else.

Many will recognize such names as Blue Mitchell, the former trumpet-player who honed his craft as a member of Horace Silver’s famed Quartet. Already a Blue Note alumni, Mitchell joined the Mainstream label in 1971, going on to record six albums for Shad’s eclectic imprint. On this compilation, taken from his 1973 Tango=Blues LP, is the sassy, San Fran TV detective soundtrack and funk version of Gato Barbieri’s sensual score for the controversial ‘butter wouldn’t melt’ Last Tango In Paris movie. With a dash of Mayfield, some gentle whacker-whacker guitar funk chops and lilt of South America, Mitchell turns a blue movie into the blues. Another former Blue Note acolyte, hard-bop and post-bop pianist LaMont Johnson, who worked with both Jackie McLean and science-fiction jazz progenitor Ornate Coleman, showcases a bit of “state-of-the-art-tech” on his kooky bendy futuristic ‘M-Bassa’ – taken from the 1972 album Sun, Moon And Stars. The rudimental phaser effects of the Yamaha EX42 analog synth augment quickening gabbles up the fretboard and echoes of spiritual jazz.

Moving on there’s a smooth, heartening and snuggled version of the rainbow nation Sly And The Family Stone’s ‘Family Affair’ by the saxophonist and flute prodigy (already able and serving his apprenticeship at the age of 13 in the Baltimore Municipal Band) Dave Hubbard; the original Muscle Shoals lit funky ‘Super Duper Love’ 45” – picked up by Joss Stone a generation later – by the sexed-up Willie ‘Sugar Baby’ Garner; the ridiculous salacious Zodiac chat-up soul-funk ‘Betcha Can’t Guess My Sign’ number (complete with Alvin the chipmonk helium backing vocals) by Prophecy; and a slick rattled percussive jazzy R&B pleaser from the saxophonist Pete Yellin entitled ‘It’s The Right Thing’.

A smattering of sampler’s delights, relatively obscure examples of jazz-funk fusions and more famous classics, Mainstream Funk is a classy and decent compilation to kick off the New Year with.

Various ‘Excuse The Mess Volumes 1 + 2’

(Hidden Notes) 4th February 2022

Across two albums of extemporized in-situ performances the great and adroit of UK-based contemporary classical and electronica experimentalism conjure up an imaginative mood board of compositions within the set perimeters of the Excuse The Mess podcast challenge. Invited for a chat in the personable surroundings of the titular space, each interview subject was asked to abide by the rules in creating a special something with the host, Ben Corrigan.

Created in that location, in that time there could be no pre-planning, no added electronic manipulations; each artist was allowed to only use a single instrument. Many of those taking part choose to use their signature instrument, others more obscured props; the most bizarre being the transmogrified ‘ice rink’ field-recorded ice-skating samples (figure-of-eight slushes and sliced ice-skate scrapes transduced into an abstract subterrain) used by the South African born multidisciplinary Warp label artist Mira Calix, and the tub patted oscillating and soft emerging techno rhythmic ‘pesto jar’ that MBE (no less) gonged electronic-acoustic composer Anna Meredith puts to good sonic use on Volume 2 closer ‘Oopsloops’.

More fathomable instruments can be detected however; for example, the renowned hand/steel pan and saucer shaped ‘hang’ player Manu Delago kicks things off by spreading his tapping fingers across his resonating percussive specialty to traverse an ambiguous cosmic atmosphere on the near-sublime ‘Collider’. Following in that peregrination’s wake is Dinosaur jazz quartet stalwart and acclaimed multifaceted composer-improviser Laura Jurd’s trumpeted ‘Copper Cult’ – a changeable vapour and march of soundtrack Miles Davis, Don Cherry and Yazz Ahmed.

In turn, the esteemed composer (pieces performed by the London Symphonic Orchestra and London Sinfonietta) Emily Hall tunes an electronic magnetic harp to ethereal heights; singer-songwriter and Erased Tape regular Douglas Dare, with just the use of his layered uttered, whispered a cappella vocals, magic’s up a dark romantic plead; and the Emmy-nominated composer and BBC 3 broadcaster Hannah Peel builds towards a shuttered clapboard rhythm and chorister-like wafted divine pirouette with just the use of a music box. Other notable inclusions (though every piece is stirring and intriguing in its own right) that piqued my attention were the fizzed and caustic frayed and slow-drawn violin evocations of the Kazakh-Brit improviser-collaborator-leader of the London Contemporary Orchestra Galya Bisengalieva – who seems to evoke Sunn O))), only with just a violin -, and the Canadian-born composer (scoring The Imposter) Anne Nikitan imagines an 8-bit Castlevania as transformed by µ-Ziq, funnelled into an early mute label version of ‘Da Da Da’.

A wealth of talent from the arts, theatre, classical and film score arenas appear on both volumes of this musical challenge: proving if anything, just how lucky the UK is to have so much talent working on its doorstep. The restrictions don’t seem to have narrowed either the quality or the originality. In fact, if anything, each artist has been creatively pushed to use their ingenuity in composing something anew, on the spot. A brilliant double-bill selection, ‘excuse the mess’ can only describe the accumulative space in which these tracks were created, and not the sounds or music, which are anything but. A novel criteria has resulted in some mysterious, spellbinding and often traversing experiments. The Hidden Notes platform ushers in a new year with a quality release package.

Brazen Hussies ‘Year Zero: An Anthology’

(Jezus Factory Records) Vinyl Version January 2022

Despite the distain, rambunctious methodology and carefree attitude to making it in the lower levels of the music scene in the 90s and early noughties, the scuzzed and abrasive Brazen Hussies were far too knowing and artful than their shambolic, contrary myth would have us believe. Quite frankly that status is shambollocks!

For this ‘lost’ London group played loosely and quite skilfully with their influences, which ranged (by the sounds of it) to everyone from Richard Hell to The Monochrome Set, from The Pixies to the Nuggets box set. Anything but a complete mess they showed a certain élan for the pivot, for the light and shade as they transitioned from the needled and coarse gnarling for halftime downtime and even a bit of melody. Because out of the ramshackle punk, post-punk and cutting dissonance there was always some remnant, a semblance of a half-decent tune.

Simultaneously as courted as they were slagged off by a hostile music press during their apex in the late 90s, it’s hard to get a handle; difficult to tell if they deserve this anthology reappraisal, or whether it’s all just a scam: elevating fleeting losers from rock’s back pages. Actually they were quite bloody good, and at least (for the majority of the time) only ever recorded three-minute songs so as not to overstay their hobnail Dr. Martens boot on the throat welcome. Their farewell ‘Bridesville’ blowout is one of the few exceptions; running to a ridiculous insufferable 26-minutes of whined post Britpop and salon bar piano malcontent.

Fronted by the duel vocals of Dave Queen (a Canadian by god) and Lou McDonnell, backed by the ‘rhythm section’ of Lunch on trebly Bauhaus-Gang-Of-Four-Killing-Joke bass duties (proving anything but out to “Lunch”) and Russell Curtis on barracking and tom rolled drums, they sounded like a contortion of the Bush Tetras and Stone Temple Pilots on the scowling ‘Touch It’; like a flange-affected X-Ray Spex on the brilliant character assignation turn halftime concerned pathos riled ‘Thin Lips’; and like the Cowboy Junkies on the country-folk-punked counterpoint of squealed industrial shredded guitar and sweeter down-heeled sung ‘Kimberley’.

In between sporadic bursts of an early Manics (Dave sails close to a young, petulant James Dean Bradford), the Stooges, Slater-Kinney, The Fall and Essential Logic they turn in two highly contrasting covers. A more obvious Seeds homage is made with a cover of the acid-garage legend’s Nuggets stalwart ‘Can’t Seem To Make You Mine’ – a real shambles of a badly recorded demo – and an odd enchanted nod to the Beach Boys’ doughy-eyed California daydream ‘All Summer Long’. It’s as if an entirely different band turned up for the second of those: well I’ve since found out that the honeyed, almost Christmas-y, Beach boys take was recorded by a flying solo Dave.

With a bedraggled smattering of releases to their name and odd appearances on a myriad of compilations, what little success they had was never capitalised on. Instead, just as those in the press that saluted their brazen despondency, protests, even heralding them as “visionaries”, they drew just as much scorn and bile. Neither a piece of crap nor the second coming, the Brazen Hussies were a great controlled mess of punk and all its off-shoots, Britpop, garage, alt-rock and skag country: in fact, a very 90s band. Is it worth the plastics melted down to produce the vinyl (digital and CD versions released back in 2021) edition? I’d say so, and I think you’ll agree when you slap it on the turntable; finding a missing link from a decade that’s increasingly becoming the new “80s”.

Hi, my name is Dominic Valvona and I’m the Founder of the music/culture blog monolithcocktail.com For the last ten years I’ve featured and supported music, musicians and labels we love across genres from around the world that we think you’ll want to know about. No content on the site is paid for or sponsored and we only feature artists we have genuine respect for /love. If you enjoy our reviews (and we often write long, thoughtful ones), found a new artist you admire or if we have featured you or artists you represent and would like to buy us a coffee at https://ko-fi.com/monolithcocktail to say cheers for spreading the word, then that would be much appreciated.