ALBUM/BOOK: DOMINIC VALVONA

PHOTO CREDIT:: Marilena Umuhoza Delli

Introduction:

Despite the multiple Grammy-award nominations and wins, and a reputation for capturing some of the most mesmeric, raw and sublime performances in the most dangerous of locations, Ian Brennan is often self-deprecating about his (obvious) talents as a producer. Ian would have us believe he merely turns up and presses the record button; that his ‘field-recordings’ are entirely serendipitous. And in some ways, this is part of his underlying philosophy: removing himself from each recording so that the emphasis is wholly on the performance. Preferring to travel (when possible) to the source, each of Ian’s recording sessions are unique and truthful.

Loosened and set free from the archetypal studio, Ian’s ad hoc and haphazard mobile stages have included the inside of a Malawi prison, Mali deserts, and the front porches and back rooms of Southeast Asia: one of which was on the direct flight path of the local airport. And yet that is only a tiny amount of a near forty release back-catalogue recorded over just the last two decades.

As if being a renowned producer of serious repute wasn’t already enough, Ian could also be considered a quality author; so far publishing four digestible tomes on a range of music topics and regularly contributing to a myriad of publications. He’s turn of phrase and candid nature brings music, the relationships, and journeys to vivid life, whilst never blanching from describing the harrowing, disturbing and traumatic realities of the geo-political situations, the violence. As a violence prevention expert, advocate, Brennan’s recordings can be said to act as both testament and a healing process.

His partner in all these projects is his wife the Italian-Rwandan photographer, author and filmmaker Marilena Umuhoza Delli, who documents each trip.

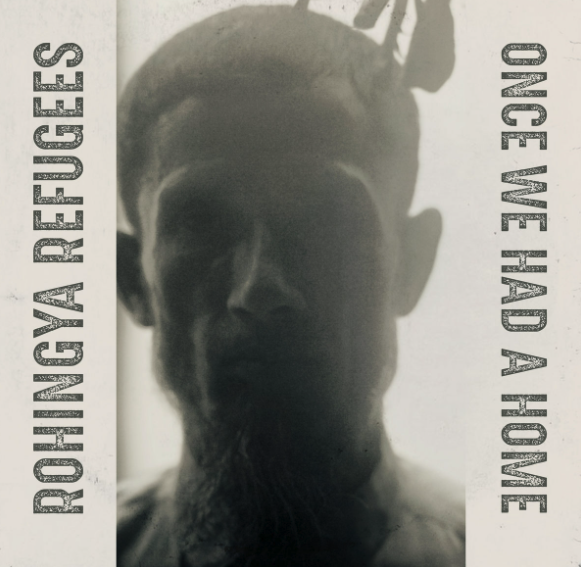

The couple’s latest project once more draws attention to a forgotten people in crisis, recording the voices of the persecuted Rohingya: terrorised and ethnically cleansed by the Myanmar government and military. A stateless population forced to flee from their age-old home in the country’s Rakhine state, a million of this ethnic group currently live in the world’s biggest refugee camp over the border in Bangladesh.

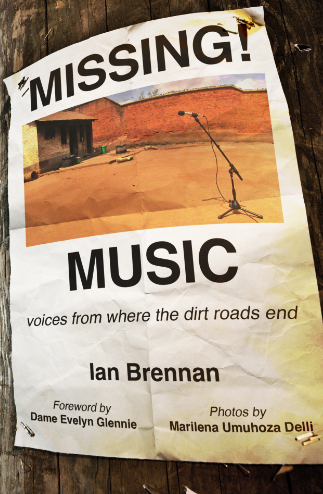

Almost simultaneously, Brennan (with Forwards from both Delli – who also provides all the photography – and the widely acclaimed percussionist Dame Evelyn Glennie) has also brought out a new book. Part “impressions”, part exploits, and part ethnography without the cliché and stiff academia, Missing Music: Voices From Where The Dirt Road Ends is a personal semi-autobiography of a lifetime’s recording work and travels; complete with polemics on the state of the world and music industry at large.

Rohingya Refugees ‘Once We Had A Home’

As attention spans seem to contract and the 24-hour newsfeed cycle is forced to update and move on every nanosecond in the battle to retain minds and lock in followers for monetary gain and validation, many geopolitical events – once seen as cataclysmic and about to push the world into climate crisis or war – seem to be quickly forgotten, usurped and replaced by the next teetering-into-the-abyss flashpoint. And so, I say, “remember the Rohingya genocide?” Of course you don’t. That’s old news. We’ve had COVID, the cost-of-living crisis and high inflation, Russia’s barbaric invasion of the Crimea and Ukraine, the continuing incursions of Islamic terrorism in Africa, the ongoing conflict and ethnic-cleansing the Tigray by Ethiopia and Eritrea, and now, since the horrific vile attacks on Israel on October 7th by Hamas, another ongoing escalating conflict in the Middle East: including Israel’s total war strategy of bombardment and eradication, and siege of Gaza. Chuck in AI and China (will they, won’t they soon invade Taiwan) and the spectre of Iran suddenly launching a full-on campaign in the region, and the hyperbolic heavy load of world problems seem too large to quantify and process, let alone solve.

Thankfully Brennan and Delli do their utmost in the face of such ignorance and crisis fatigue to draw attention to one of the world’s worst forced movements of people. Escaping what has been defined in international law as genocide – accusations the Rohingya’s oppressors Myanmar face in the International Court of Justice in The Hague – the Rohingya ethic grouping of people claim their descendance from 15th century Islamic traders. But it’s thought that they probably arrived in what is now Myanmar (formerly Burma) via various historical waves of migration over time: from the ancient to Medieval. The Buddhist majority Myanmar’s history is full of origin stories and diversity. The government has its own list of “national races” no less: a 135 in total. Missing from that list however, the near wholly Muslim practicing Rohingya are referred to as “illegal migrants”; mere squatters on the land they’ve cultivated and shared for at least a millennium.

Dating back to the 1970s, the military juntas – the more recent short flirtation with a less than democratic system, now looking like nothing more than a blip, a footnote in the country’s story – have constantly persecuted this group, which before the genocidal campaign of 2017 numbered 1.4 million or more. Essentially stateless, and hunted down, displaced, a vast majority are confined to the world’s largest refugee camp in Bangladesh: although many have fled much further abroad and throughout more accommodating South-eastern Asian countries. A sick twist to this persecution and removal, the Myanmar military are forcibly conscripting the Rohingya to help fight an ongoing conflict with the Arakan Army in the region of the Rakhine State. Founded in 2009 to win self-determination for themselves, the Arakan are yet another convoluted thread to the story of woe; another ethnic group fighting to achieve their aims. And just to muddy the waters even more, the Arakan Army also features the Rohingya amongst its ranks.

Myanmar’s government would in their defence cry foul, that they were fighting insurgents, illegals, and terrorists. There have been incidents up and down the border, with the murder of police and military by both groups. And the Arakan have embarrassed the military, winning huge swathes of the Rakhine against a far superior and numerical army.

Within the makeshift camps, set up in the aftermath of Myanmar’s most brutal act to date – the full-scale programme of ethnic cleansing from its lands -, gangs roam and prey on the vulnerable eking out an existence in the face of extreme poverty and limbo. The future looks bleak, even with international condemnation, with no hope of return, of justice. In highlighting “hidden voices” and finding the rawest of accounts, their both poetically sung, and achingly voiced testaments are recorded for posterity by Brennan, who’s hands-off approach removes the barriers between recordist and performer. Ernest collected ethnography can take a walk, for this is above all about bringing authenticity and the marvels of the untainted, uncollyed and (cliché as it is, it still stands) the truthful to our ears. Because the remarkable thing about all of Brennan’s work is the way he introduces us all to revelatory sounds and connections.

Within the refugee camp, and despite the severe conditions, most of the recordings are incredibly lyrical and melodic to the ear: even when the musical accompaniment of percussive chings and shakes, entwinned plucks and occasional singular wooden box-like hits are minimal. Musically crossing borders with every caress, strike and either brassy or percolated drone, you’ll hear elements of the Islamic, of India, the Caucuses, Pakistan, Indonesia, Thailand and of course Myanmar. And despite the traumatic subjects, the crimes against humanity, even the harrowing testament can sound like an intimate courtly piece of theatre or a purposeful, softly placed dance. That goes for the yearning, near pleaded declarations of love for both soul mates and home too – although without the context, one echoed aching soul’s declaration, if unrequited or stopped, threatens to “hang” themselves.

The titles of these recordings certainly pull you back into the reality of their desperate plight, with reminders that this campaign against them is fuelled in part by religious nationalism (‘The Soldiers Burned Down Our Mosque’), but that sexual violence is a common weapon in that persecution (‘Let’s Go Fight The Burmese (They Raped Our Women))’.

As with most of these projects the revelation is not only in hearing such original and moving voices but in picking up what could be the very roots of musical forms that we’ve taken for granted or taken as our own. The soulfully lamentably exhaled ‘My Family Prays For Us To Come Home (Here We Have No Life At All)’ I swear has the very seeds of gospel music and the blues within its Rohingya folk traditional soul. And I seriously swear I can detect a Catskills-like banjo on ‘Let’s Go Fight The Burmese (They Raped Our Women)’ . It’s obviously not of course, as I’m sure it’s an instrument more native the climes and geography of Southeast Asia than Americana.

Once more it’s beauty that shines through the distress; the musicality of burning hope in the face of anguish and violence still connecting and making heart’s sing. Brennan’s minimal interference (although that’s not really the right word for it) allows for the most pure, candid, and unforgettable of raw performances. Without overdoing it, or using too many superlatives, these projects are amongst the most important documents of their kind; bringing the harsh realities of the forgotten Rohingya people to public notice in the hope that their story is heard: we can’t pretend we never heard it!

Book: Missing Music – Voices From Where The Dirt Road Ends (PM Press)

Ian Brennan has a real knack for writing; a visceral way of setting the scene, the danger and geo-political circumstances and context without succumbing to boring platitudes or stiff academic dullness. He certainly can’t be accused, unlike so many “worthy” signally publications and sites, of sucking the soul out of the music he writes about; like all the best writers, someone who actually loves music in all its forms. Brennan the celebrates what cannot be quantified or bottled: or for that matter sold! In fact, you could say he was in a continuing, constant, battle against the corporate forces of greed and consumerism, riling at the commodification of art.

Brennan has written several books in support of artists outside the Western sphere of influence, whilst also attacking the onslaught of “muzak”. But. How you open up ears and widen the appeal of independent voices and those musical forms from such far-flung pockets of the world as Cambodia, Malawi or São Tomé is anyone’s guess: I’ve tried for over two decades, finding it a total myth that each new generation, growing up in the age of the Internet and with access to the world’s music catalogue at the swipe of a screen, is somehow more eclectic – the short answer is, no they are not.

The horrible and lazy “world music” term – as Brennan would say, “all music is world music” – fetishizes those it seeks to label. But then again, plenty have tried to celebrate and promote those same voices and artists” WOMAD being the most glaringly obvious example, but literally 1000s of labels, from major to cottage industry independents. And yet, even as certain names fly, take hold, and capture Western audiences and build up sizable numbers online, they’re demoted to playing the “world stage”: demarcated and separated. If anything, we’ve gone backwards, with the main events dominated by the so-called “urban” stars, vacuous tiktok sensations and heritage acts (not wholly “white” I might add). Gone are the days when Kuti could share the same space as some Western rock act; even jazz, no matter the constant bullshit promoted trend to declare its renaissance and popularity, can’t get a main stage slot at any major festival. Don’t get me started on the advancing AI takeover of the arts and music; the future already here as thousands spend a fortune to see avatars of stars still alive and able to perform – namely that God awful ABBA production; the quartet rendered by tech to appear eternally youthful and at their peak. Now every artist is forced to compete with everyone whoever existed, dead or alive, for attention and support. In that climate Brennan champions a far humbler cast of artisans and amateurs alike, from the incarcerated soulful voices of the Mississippi penal system to the late North Ghanian funeral singer Mbabila “Small” Batoh and sagacious atavistic-channelling old folk of Azerbaijan.

Choosing just a smattering from a catalogue of at least forty releases over the last decade or more, Brennan’s latest book, Missing Music – Voices From Where The Dirt Road Ends collects together some of his most personal recording experiences. In fact, it reads in part like a winding autobiography along a road less travelled, with Brennan highlighting his older sister Jane’s struggles with Downs syndrome, whilst panning out to address the lack of social care, the stigma, and disparities at large in the American health care system. You can hear Jane’s voice and pure joy of expression on Who You Calling Slow?, recorded by Brennan and released under the Sheltered Workshop Singer title. Apart from his Rwandan recordings (his half Rwandan half Italian wife and partner on these projects, Marilena Umuhoza Delli’s family was forced to flee the genocide) I believe this project (and book chapter) is the closet and most personal to Brennan’s heart. Having to watch during the hands-off, isolated bleakness of COVID as his sister retreated into her shell, his words are a testament to the (cliché I know, but if it could be used with any real sincerity it’s here) power of music therapy.

“Just for the fuck of it” , the journey Brennan makes is an inter-personal, academic free one, with life-affirming stepovers in Suriname (‘Saramaccan Sound’), Bhutan (‘Bhutan Balladeers – Your Face Is Like The Moon, Your Eyes Are Stars’) and most rural outposts of Africa (‘Fra Fra – The Quiet Death Of A Funeral Singer’). That last chapter deals with death quite literally; marking the passing of Fra Fra’s Mbabila “Small” Batoh, who led the northern Ghanian trio of funeral singers and players. Primal, hypnotic with various sung utterances, callouts, hums and gabbled streams of despondent sorrow they personised the process of grief. But sounded like the missing thread between African roots music, the blues, and New Orleans marching bands. Incredible to hear – which you should if you haven’t already – it’s artists like “small” that Brennan truly rates: holding them up on an equal pedestal with the best the West has to offer in the roots stakes. Unfortunately, the enigmatic Djibouti artist Yanna Momina, star of the Afar Ways album of recordings, also passed away – I made a little tribute in last July’s Digest column. A member of the Afar people, an atavistic ancestry that spreads across the south coast of Eritrea, Northern Ethiopia and of course Djibouti (early followers of the prophet, practicing the Sunni strand of the faith), Momina was a rarity, a woman from a clan-based people who writes her own songs. Once more Brennan summons up the right words, expressions, and scenery in bringing her legacy to life.

More like the best of traveling companions, guides, open to adventure, Brennan’s writing balances joyous connections with the dangerous conditions in which he finds himself. Little details say so much in this regard, with the almost incidental sentence and anecdote about being cautioned to not use his first name of Ian because it sounded Armenian, when crossing the flashpoint and stepping into the continuing conflict between that country and Azerbaijan to record ‘Thank You For Bringing Me Back To The Sky’. But of course, when out of choice, traveling to such danger spots is either lunacy or brave, and along the way there’s plenty of discouragement and warning.

Anything but a thrill seeker, Brennan’s role in violence prevention makes it a vital part of his job; gaining a better understanding and knowledge from the horse’s mouth so to speak. Many of his impromptu sessions are therapeutic in allowing victims to speak about their trauma in the most unsympathetic of climates. The very roots of all Western music no less, Brennan freely comments on the disparity of fortunes between the artists detailed in his book and those in the English-speaking West – a language, statistically that sells more volumes and traction than any other. Arguments and studied polemics are made, politics auspice and solutions put forward against the blandification of the music industry and our environment – for example, why do so-called hip independent signalling businesses, such as cafes play such uniform bland, enervated and commercial music that’s the very opposite of their principles and mantra; Brennan says we shouldn’t take that crap and point it out to the barista the next time this background soundtrack insults our ears.

Of those “timeless voices”, which should be amplified, this little passage is one of the best: “Rather than seeking charity, theirs is the charitable act – truth offered without expecting anything in return. The only desires, connection.”

As a celebration that faces the hard truths, this book is a must read and guide to new and more deserving sounds from around the world; for these artists have more going for them, are closer to the pure soul, motivation and expression of music than the majority of fake acts and vaporous stars that do unfortunately dominate the airwaves and social media.

Ian Brennan on the Monolith Cocktail: Check out just a smattering of his projects I’ve reviewed, plus a very special interview from a while back.

Tanzania Albinism Collective ‘White African Power’

Witch Camp (Ghana): ‘I’ve Forgotten Now Who I Used To Be’

The Good Ones ‘Rwanda…You See Ghosts, I See Sky’

Ustad Saami ‘Pakistan Is For The Peaceful’

Sheltered Workshop Singers ‘Who You Calling Slow?’

Comorian ‘We Are An Island, But We’re Not Alone’

The Oldest Voice In The World (Azerbaijan) ‘Thank You For Bringing Me Back To The Sky’